Fashion and Disease Prevention

Agnese La Spisa

Surprising Origins of Iconic Trends – Fashion and Disease Prevention

Fashion has always been more than appearance. In many cases, styles were born not only from creativity but also from necessity. Epidemics, sanitation problems, and social fears shaped what people wore, illustrating how fashion trends disease prevention have historically intersected. Some of the most iconic fashion trends in history were actually designed to prevent disease, conceal illness, or signal health and status.

Below are six striking examples of fashion’s hidden connection with survival.

High Heels: From Stirrups to Sanitation

The history of high heels begins in 10th century Persia. Horsemen wore them to secure their feet in stirrups, giving them an advantage in battle. When heels spread to Europe, their purpose shifted dramatically.

Medieval cities were notorious for unsanitary conditions. Streets were filled with mud, animal droppings, garbage, and human waste. Cuts on feet could easily lead to infection. Elevated shoes, later called chopines, lifted nobles above the filth. By the 1600s, the higher your shoes, the more protected you were from sewage and disease carrying waste.

These shoes were not about elegance at first. They were a public health measure and an early example of how fashion trends disease prevention were closely linked. Yet, what started as protection became a symbol of power and prestige. Today’s high heels are descendants of footwear that once helped people survive dirty urban environments.

The Beaked Plague Mask: A Primitive Shield

During the bubonic plague outbreaks of the 17th century, physicians became famous for their terrifying bird-like masks. The long beaks were stuffed with herbs, vinegar-soaked sponges, and spices. Doctors believed these substances could filter “bad air” or miasma, thought to spread the plague.

Although these masks offered little real protection, they represent one of the earliest attempts at infection control. They were both medical tools and grim fashion statements, symbolizing fear, death, and the desperate human fight against an invisible enemy. This is another example of how fashion trends disease prevention intersected in history.

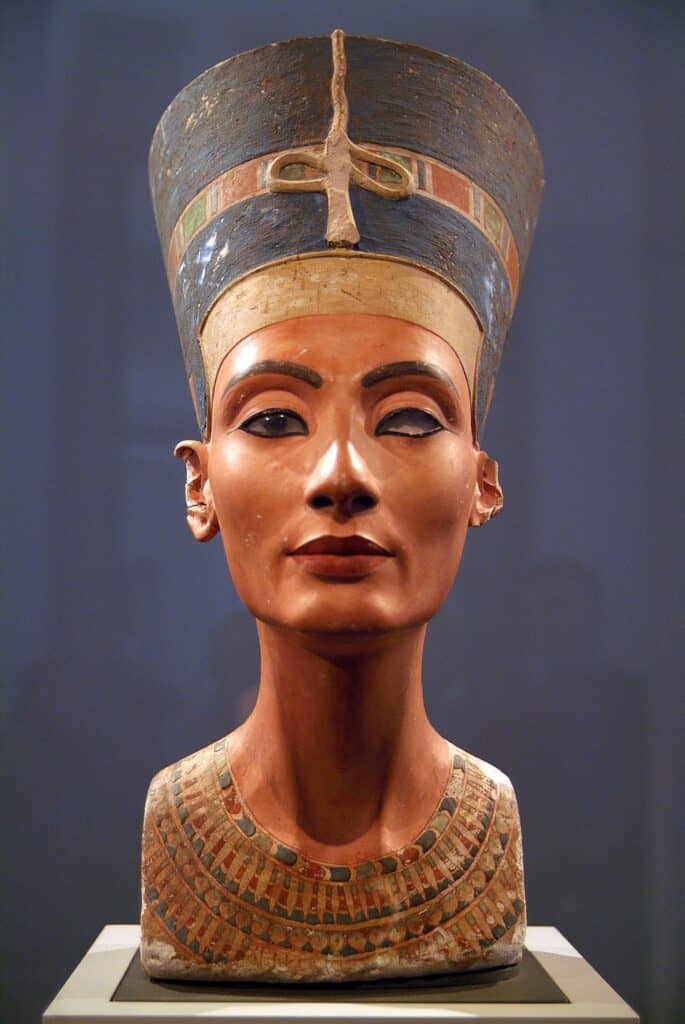

White Face Powder: Pale Skin and Poison

A pale complexion has often been admired, but in history, it also carried health-related meanings. Pale skin suggested that you did not work outdoors, where insects, contaminated water, and harsh sun increased exposure to disease. But pale skin was also used to hide scars from smallpox, one of the deadliest illnesses of the early modern world.

Queen Elizabeth I famously wore Venetian ceruse, a white powder made of lead carbonate. It provided flawless coverage but slowly poisoned the body. Continuous use caused skin eruptions, which wearers covered with even more powder. Eventually, it led to disfigurement, organ failure, and death. Maria Coventry, Countess of Coventry, illustrates the dangers. Known as a great beauty, she used Venetian ceruse faithfully. By age 27, she died of lead poisoning, remembered by the public as “Death by Vanity.” Despite widespread knowledge of its risks, many continued using ceruse because it adhered well to skin and created the fashionable look of the time.

Other cosmetics of the 16th and 17th centuries were equally dangerous. Some contained mercury or acids, which stripped the skin or blocked melanin production. Beauty ideals came at the expense of health, yet people were willing to pay that price to maintain the pale look that signaled status and disease resistance. The use of such powders also demonstrates early intersections of fashion trends disease prevention.

Powdered Wigs: Concealing Syphilis and Fighting Lice

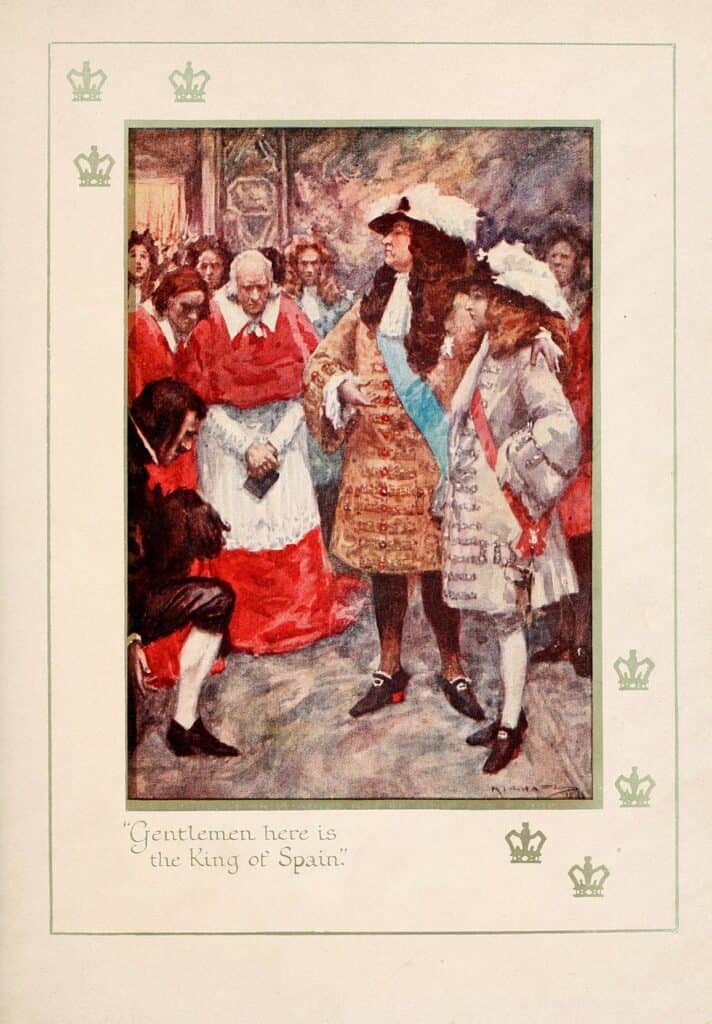

In the 17th and 18th centuries, wigs became synonymous with elegance. Their popularity, however, was tied to disease. Syphilis, rampant among the wealthy, caused hair loss and sores. Wigs offered a way to hide these symptoms, showing how fashion trends disease prevention were closely intertwined.

Louis XIV of France began wearing wigs after he started losing his hair at just 17. His cousin, King Charles II of England, was also a devoted wig wearer. Their influence made wigs fashionable across Europe, turning medical concealment into a cultural trend. Beyond syphilis, wigs served another purpose. By shaving their heads, people made wigs fit better, and lice infested the wigs instead of the scalp. Wigmakers often deloused them, sparing their clients constant itching. Though not pleasant, wigs acted as parasite traps.

This fashion eventually declined. Heavy taxes on hair powder and revolutionary backlash against aristocratic excess led to wigs’ downfall. But for a century, they were essential tools for health concealment and comfort.

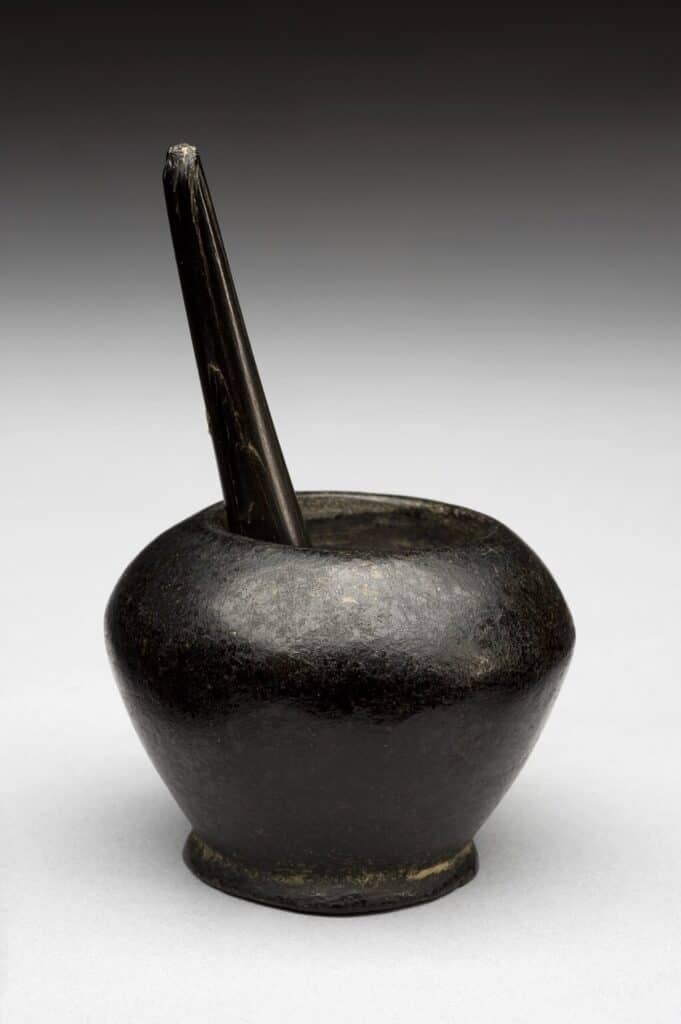

Kohl Eyeliner: Cosmetic with Medical Benefits

The dark eyeliner of ancient Egypt was not just about beauty. Kohl, made of galena and other minerals, had antimicrobial properties. Research shows it helped prevent eye infections in desert climates. Egyptians also believed it offered protection against sunlight and the evil eye. Children and adults alike wore kohl, blending ritual, medicine, and aesthetics. Thousands of years before antibiotics, kohl served as both a cosmetic and preventive treatment, making it a remarkable early example of fashion trends disease prevention.

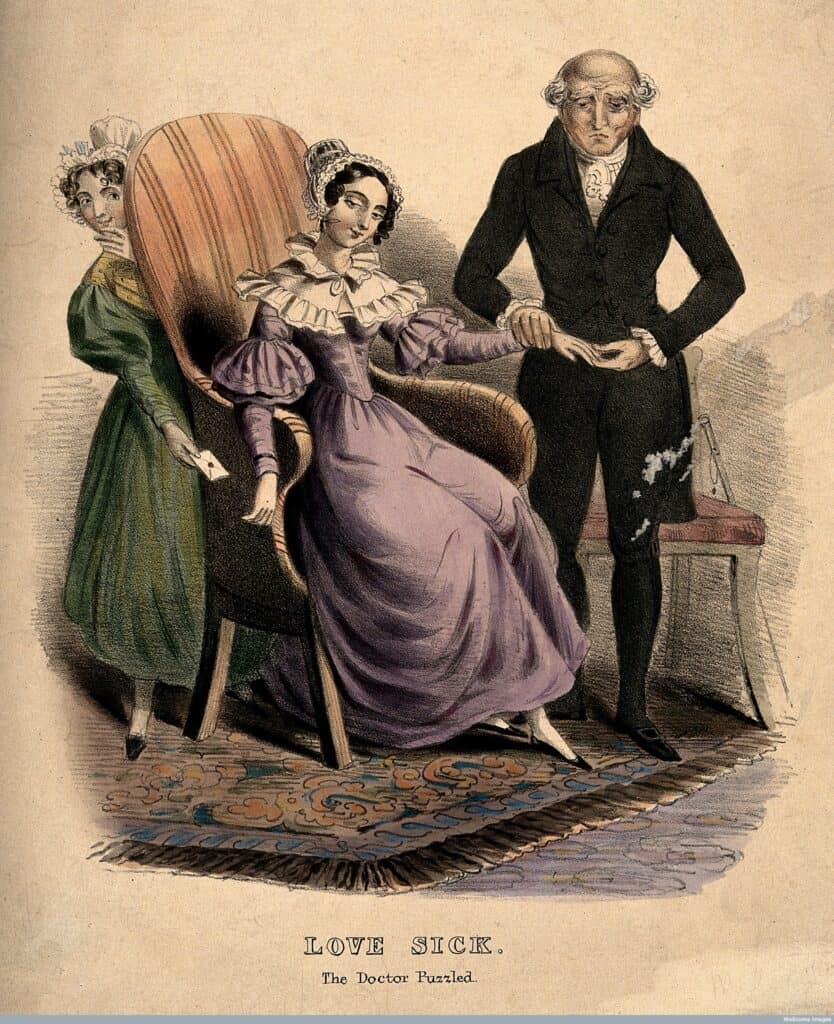

Tuberculosis and the “Consumptive Chic”

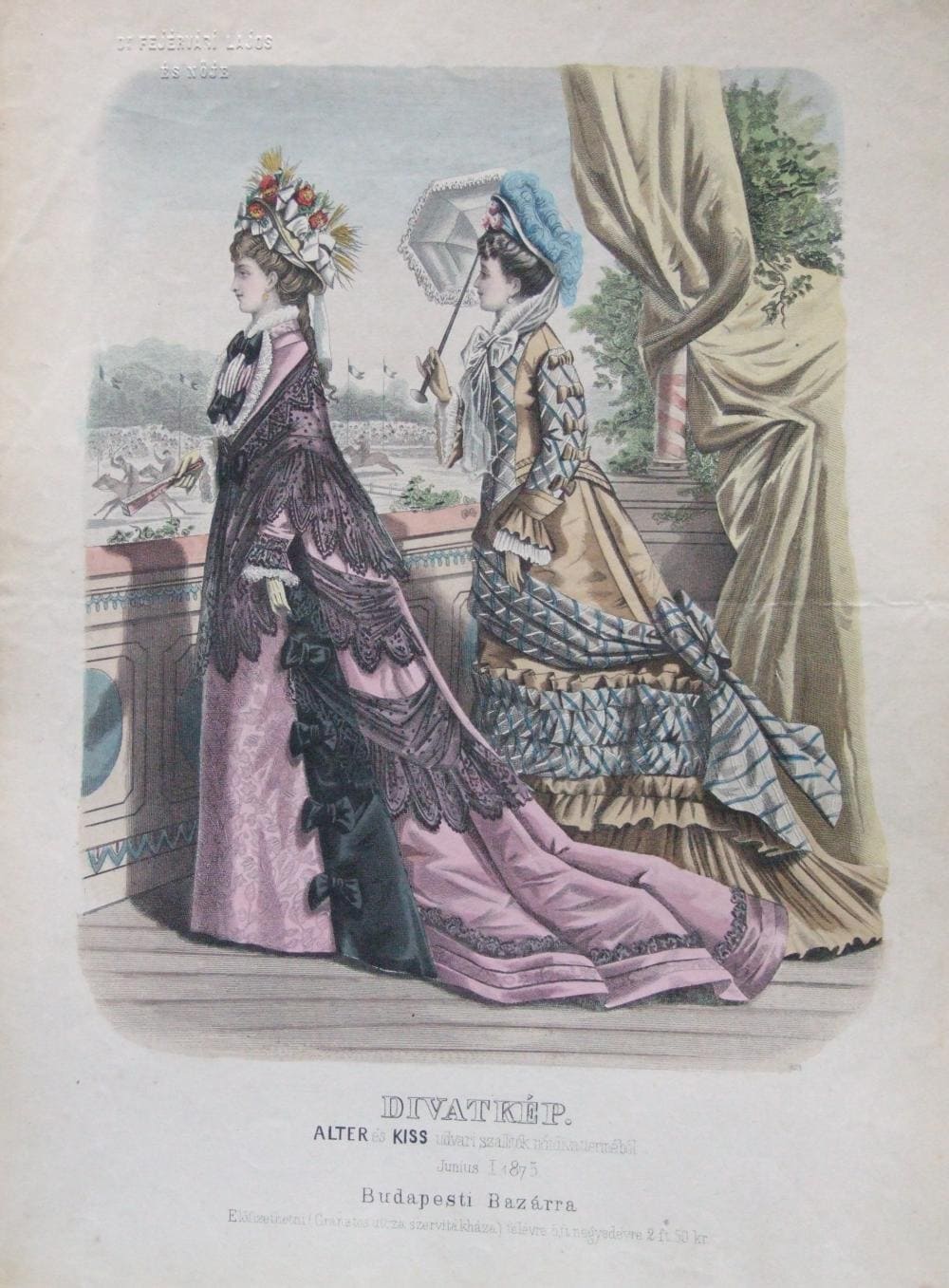

In the 19th century, tuberculosis, or “consumption”, was one of the deadliest diseases in Europe. Yet strangely, it shaped beauty standards. The illness caused pale skin, flushed cheeks, bright eyes, silky hair, and extreme thinness. These symptoms became fashionable, giving rise to the “consumptive chic” ideal.

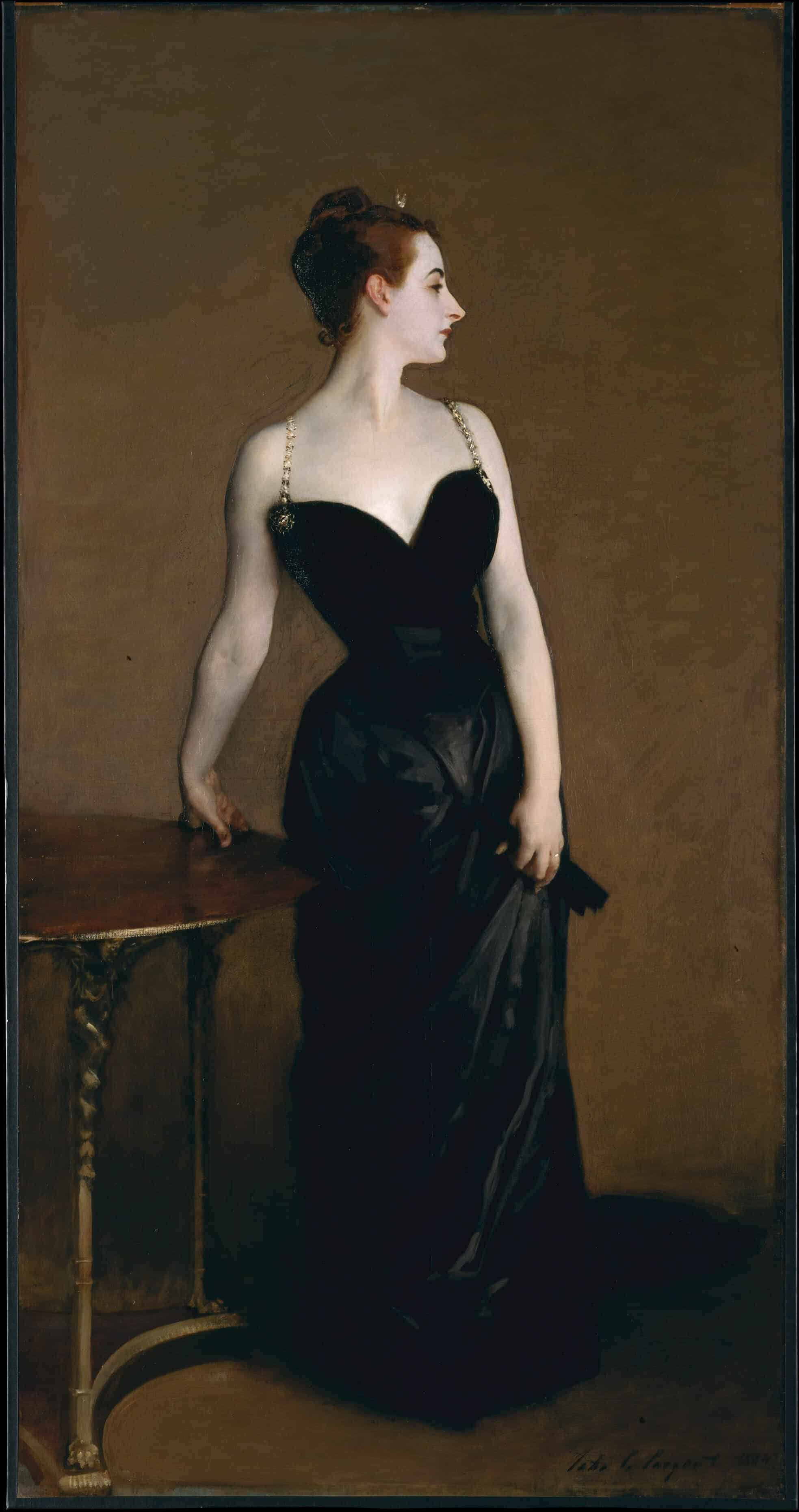

Women tightened their corsets to achieve waists as thin as those of the sick. Others used lavender powders, arsenic wafers, and even toxic blushes containing lead or potassium chlorate to imitate the appearance. The Parisian socialite Virginie Gautreau became famous for her consumptive look. She emphasized her pallor with lavender powder, painted veins with indigo, and tinted her ears with rouge. Artists celebrated this fragile beauty. John Singer Sargent’s portrait of Gautreau, Madame X, immortalized the consumptive aesthetic. Newspapers often praised her appearance, even though her beauty regimen involved highly toxic substances.

Eventually, tuberculosis lost its strange glamour. Once it became clear that the disease was contagious, the ideal faded. Still, consumptive chic left its mark, reminding us that even tragic illnesses influenced fashion trends disease prevention.

Fashion, Health, and Human Survival

Across centuries, fashion has been closely tied to illness. High heels kept wearers above disease-filled streets. Plague masks reflected early ideas about airborne protection. White face powders concealed scars but poisoned their users. Wigs hid syphilis and trapped lice. Kohl eyeliner prevented eye infections. Tuberculosis shaped a tragic but influential aesthetic.

These examples prove that style was rarely about vanity alone. Fashion trends disease prevention often reflected the realities of survival, environment, and disease. The next time we admire historical beauty trends, we should remember the hidden health stories behind them.

CREDITS

Photo 1: Hyacinthe Rigaud, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo 2: Louis XIV of France, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo 3: Roberto Barone ph, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo 4: Unidentified painter, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo 5: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/71846556528109388/, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo 6: After Godfrey Kneller, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Phot 7: Nicolas de Largillière, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo 8: See page for author, CC BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo 9: Giovanni from Firenze, Italy, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo 10: See page for author, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo 11: John Singer Sargent, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Share this post

Agnese La Spisa is an Italian creative based in Italy, specializing in publishing and fashion communication. At IRK Magazine, she brings together creativity, research, and design to shape stories with clarity and style. Curious and collaborative, she is driven by a passion for exploring culture, aesthetics, and the narratives that connect people, ideas, and disciplines.

Read Next