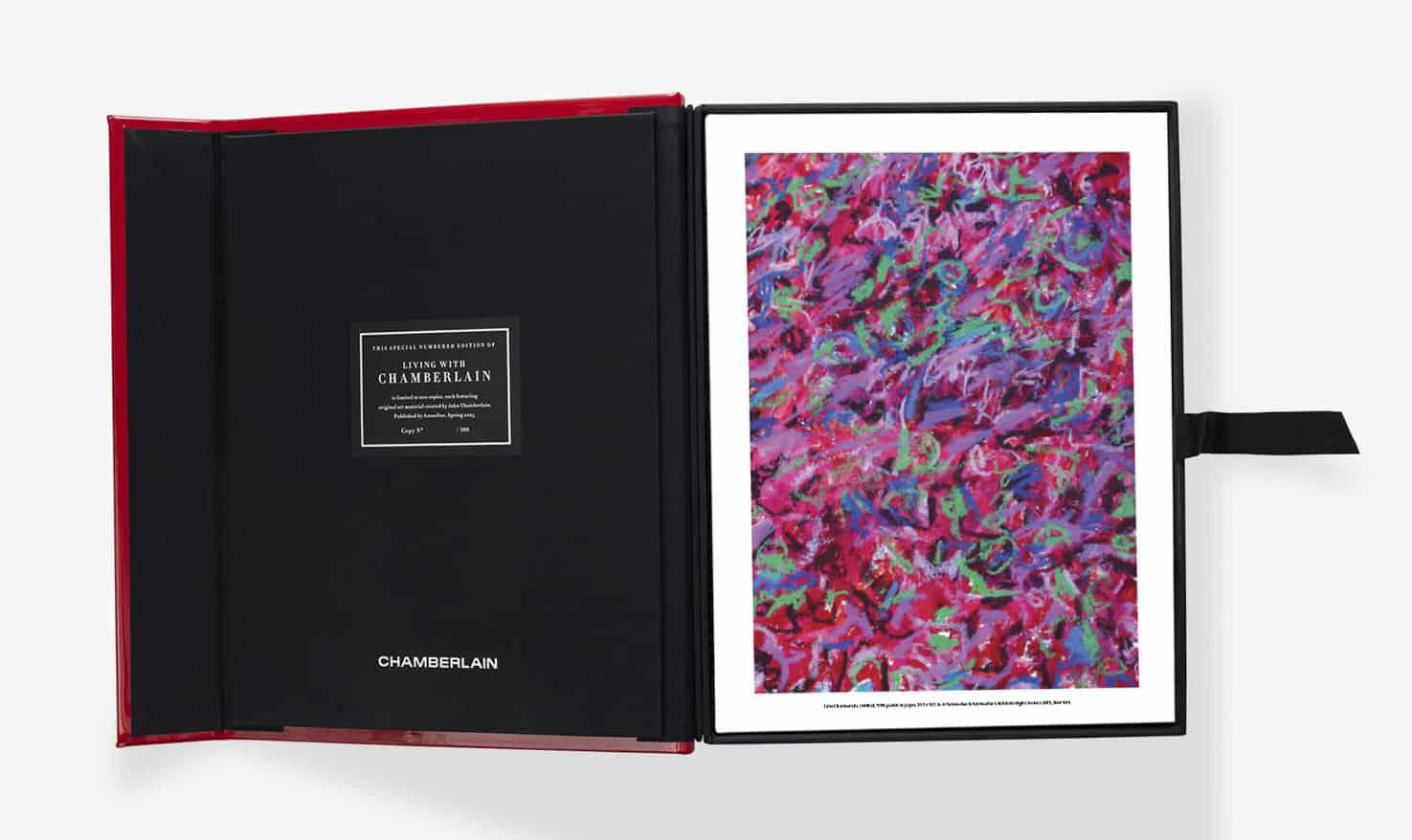

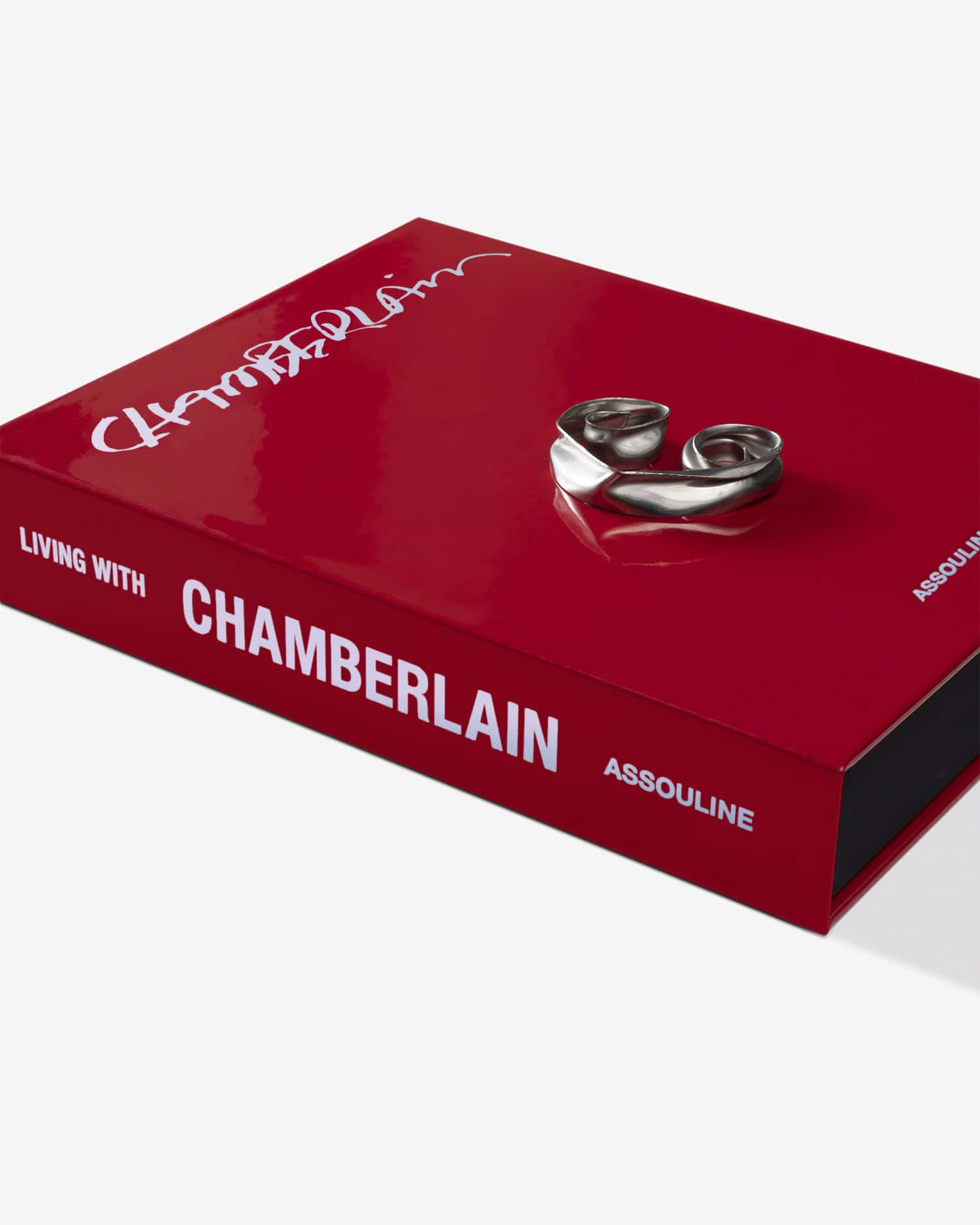

Living With Chamberlain – Book Review

Mia Macfarlane

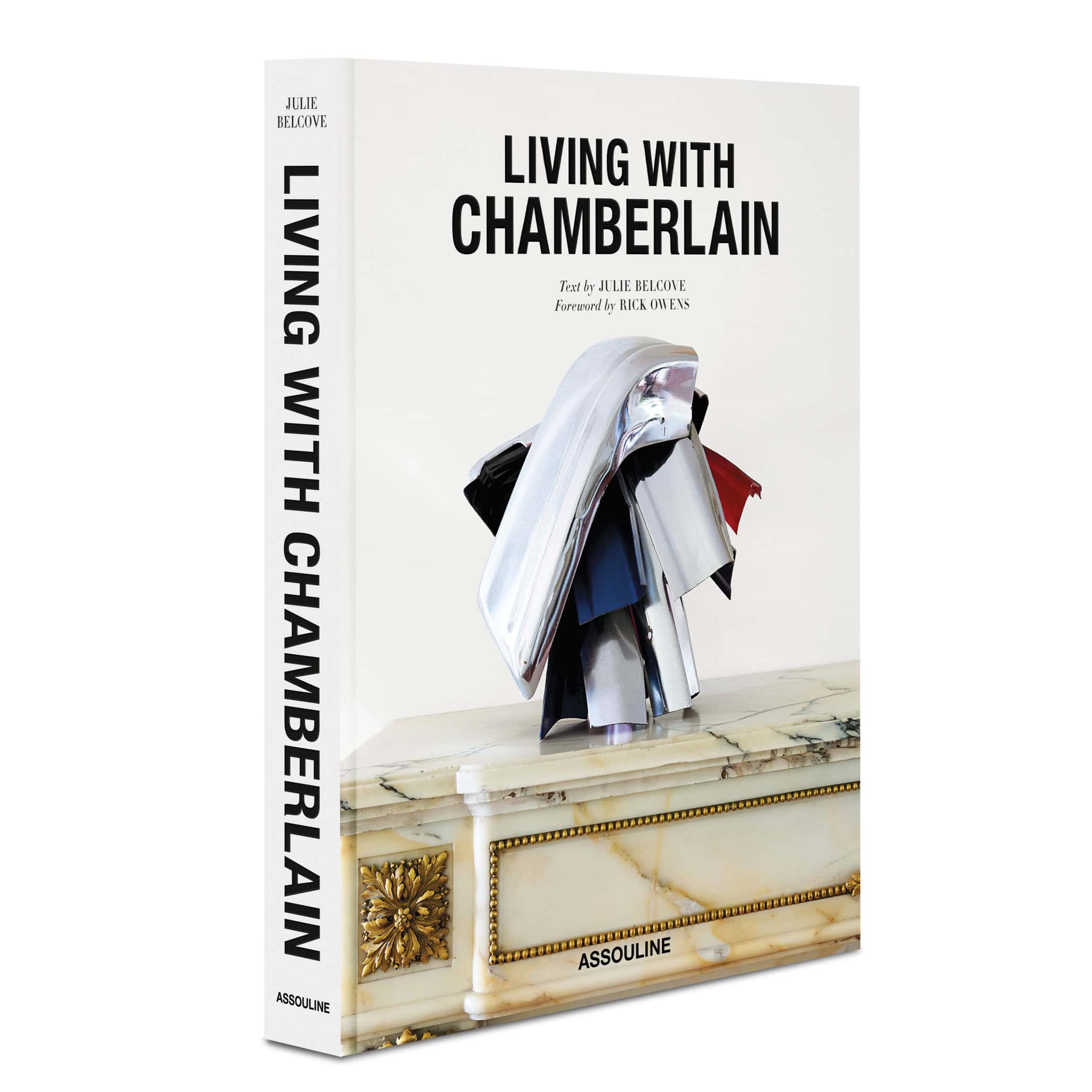

“Living With Chamberlain” is not a typical Assouline monograph. Instead, it is a massive, intimate portrait of John Chamberlain, a sculptor who turned crushed metal into meaning. The book reads like a biography, an oral history, and a record of how people actually live with work that refuses to sit quietly. Moreover, it becomes a study of how one artist’s presence continues to shape rooms, relationships, and memories.

image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

A Life Built on Scrap Metal and Attitude

Rick Owens opens the book with a memory that sets the tone. He recalls discovering Chamberlain’s sculptures in art school and seeing “angels and candy and blood” in the mangled metal (pages 4 to 5). From there, the book traces Chamberlain’s path from a lonely Depression era childhood to Navy service, then to working as a Chicago hairdresser, and ultimately to his epiphany at Black Mountain College. Finally, it lands on the first fender he tore off a rusted Ford in 1957 (pages 9 to 13). Consequently, that single act led to Shortstop, the sculpture that defined his language and launched his career.

The biography does not sanitize anything. Instead, it confronts the fights, the late nights, the affairs, the impulsive moves, the junkyards, the bar scenes, the drinking, the foam sculptures, the boat years, and the revolving studios. All of it appears through the people who loved him, tolerated him, and occasionally dragged him out of trouble. As a result, the portrait feels real.

Island. Photo Jason Schmidt © Ventura Capital Advisors

LLC. © Fairweather & Fairweather Ltd/Artists Rights

Society (ARS), New York

Where the Book Becomes Powerful: Living With the Work

The book’s most revealing sections are not about the sculptures themselves. Rather, they are about how people live with them. Because Chamberlain’s works dominate a room, the book shows exactly how they alter space and atmosphere.

Living With Chamberlain presents chrome towers in minimalist homes, crushed metal spirals in foyers, Baby Tycoons on coffee tables, and monumental works installed beside swimming pools or next to Brice Marden canvases. In addition, it captures the way people adapt their homes around these sculptures instead of the other way around.

Vera Wang explains how his forms strengthened her own thinking in 360 degrees (pages 112 to 119). Meanwhile, collectors like Judy and Jeff Greenstein literally built a wall in their home to hold Char-Willie (page 204). Other collectors describe how a Chamberlain becomes a presence rather than an ornament. A few even describe it as a family member.

The emotional stories are even stronger. Some pieces were wedding gifts. Others became anchors in childhood memories. One collector placed her sculpture on a rotating plinth so she could spin it and rediscover it each day (page 202). Therefore, the book makes one point clearly. A Chamberlain does not decorate a room. It bends the room to its will.

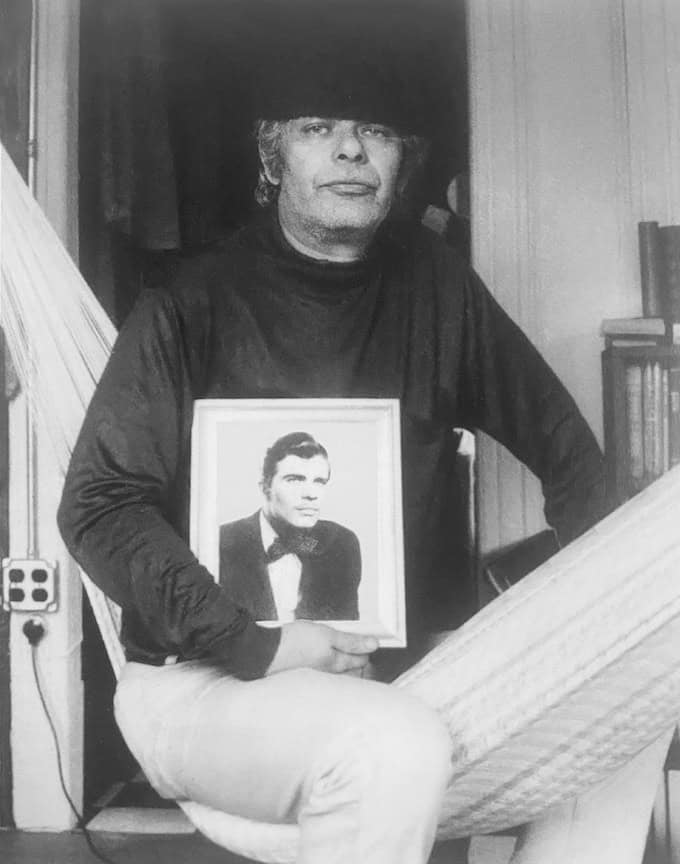

Chamberlain as He Was: Unfiltered

Julie Belcove does not soften Chamberlain’s character. Instead, she shows him as sharp, funny, sensitive, impatient, magnetic, and allergic to pretension. Because he resisted over-intellectualization, he insisted the work was not about cars. To him, car parts were simply material. They were free, they were available, and they could take a hit without complaining.

“If a thing is made intuitively then why look at it intellectually” (page 76). Chamberlain said

He believed two pieces of metal either belonged together or they did not. No theory needed.

He also loved jazz. It shaped the way he made sculptures. His daughter says he worked the way a saxophonist improvises: a gesture, a pause, another gesture, and then the moment it clicks (pages 32 to 33). Consequently, the work feels rhythmic rather than rigid.

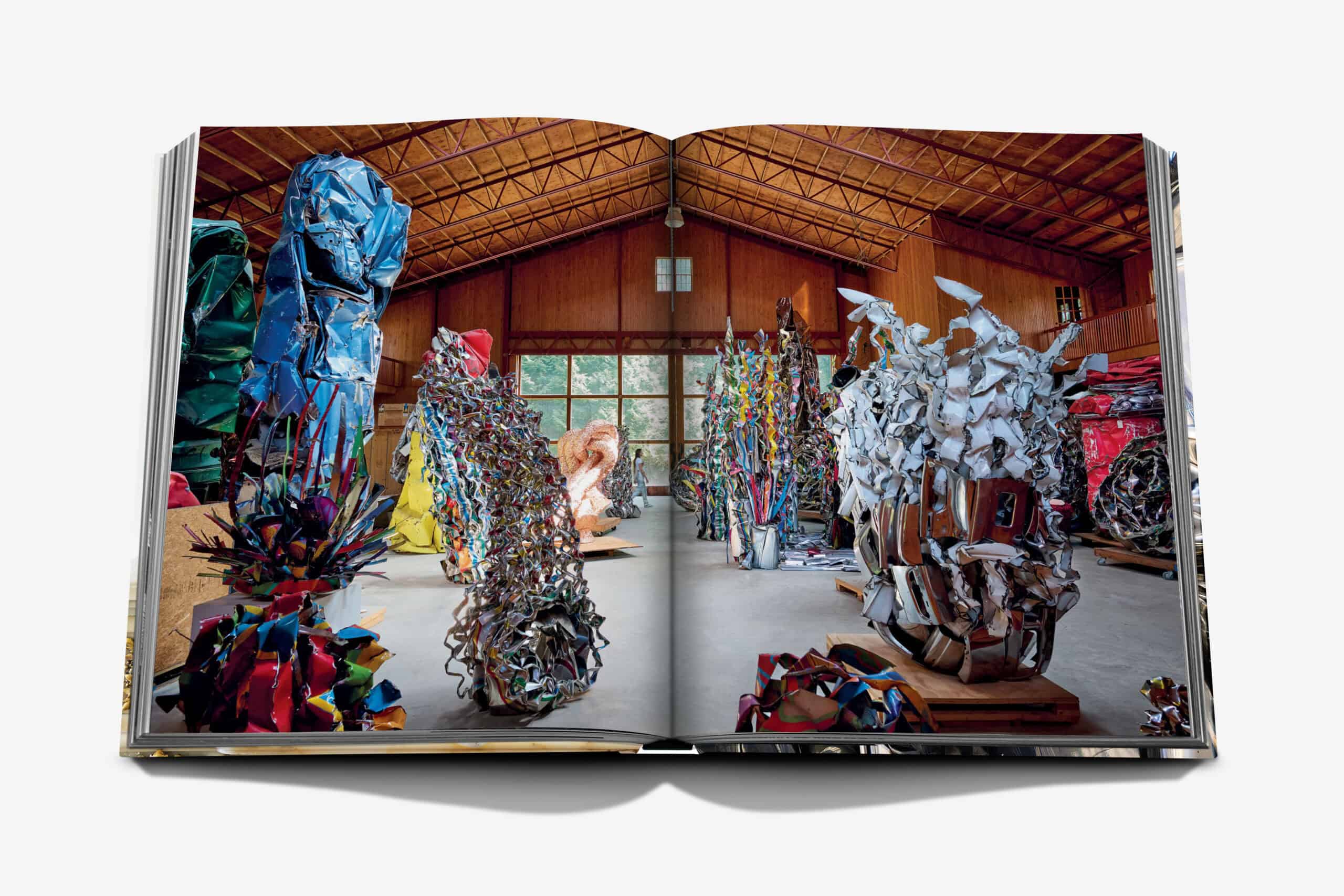

The Structure of the Book

The photography is striking. Full bleed images show both the monumental pieces and the small works. His Shelter Island studio appears like a cathedral of steel and colored metal (pages 32 to 37). Furthermore, the Marfa shots show how his works occupy space with a force similar to architecture (pages 28 to 29).

The book is paced like a film. It moves from early archival images to large color plates, then to portraits of collectors and their homes, and afterward to the personal stories that reveal who Chamberlain became in his final years. As a result, the pacing keeps the narrative active and alive.

Why It Matters Now

Chamberlain’s work feels particularly relevant today. In a moment dominated by over-explanation, conceptual art statements, and digital workflows, his sculptures remind us of something feral and instinctive. They are physical, invite touch, demand attention, and reject politeness. Moreover, they make a strong argument for intuition over theory.

He was recycling metal decades before sustainability became a cultural value. Therefore, his sculptures show what happens when waste is treated as raw possibility instead of trash.

Above all, the book shows how art behaves in real homes. Not white cubes. Not museum pedestals. Real spaces. Real lives. Consequently, the work becomes part of daily movement and emotion rather than a distant object.

For IRK readers who live at the crossroads of art, fashion, and cultural risk taking, this book feels like a manifesto for living with art that refuses to behave.

Chamberlain work on the coffee table. Photo Jason Schmidt ©

Ventura Capital Advisors LLC © Fairweather & Fairweather Ltd/Artist Rights

Society (ARS), New York © 2025 Estate of Brice Marden/Artists Rights

Society (ARS), New York © Archiv Franz West, © Estate Franz West

Verdict

“Living With Chamberlain” is chaotic, human, emotional, and completely alive. It restores Chamberlain to the scale he deserves and is a powerful yet intimate art book. Ultimately, it is a great gift for anyone who believes that art should challenge, confront, and leave a mark.

Share this post

One day when I was barely two my mom let me push her out of her bedroom. She was curious so she ran outside the house so she could watch me through the window. I climbed up on a chair by her vanity and started putting on her makeup. I loved playing dress up as a kid. Putting on my mom's sequin tube tops and high heeled shoes and then putting on a dance show in the lobby or the restaurant of the hotel/residence we lived in. It was the best childhood ever. Dress-up, dancing, playing with barbies, and drawing were my favorite things to do. I have not changed one bit today. If I am creating I am happy.

Now I am in Paris for the second time in my life and I am having a ball playing with my partner in crime Julien Crouigneau. We founded IRK Magazine together in 2015 and we are proud to collaborate with some amazing artists, and influencers.

We are also a photography duo under the pseudonym French Cowboy. We love to tell stories and create poetic images that are impactful.

Read Next