Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up

Natasha Hall

An exhibition exploring the artwork of Frida Kahlo in the context of the photographs, objects, clothes, intimate and personal items that document her life, will open this weekend at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Her tragic struggle with illness started with contracting Polio in 1913, being severely injured in a tram accident in 1925 which led to her painting whilst bedridden. She started wearing a medical corset in 1926, had numerous operations on her spine, miscarriages and abortions on medical grounds, had toes removed and finally when her foot became gangrenous, had her right leg amputated below the knee and died the following year on the 13th July 1954, aged just 47. This exhibition is a fresh insight into her compelling life story, but it is so much more than the details of her life, of her struggle and her resilience in the face of physical suffering.

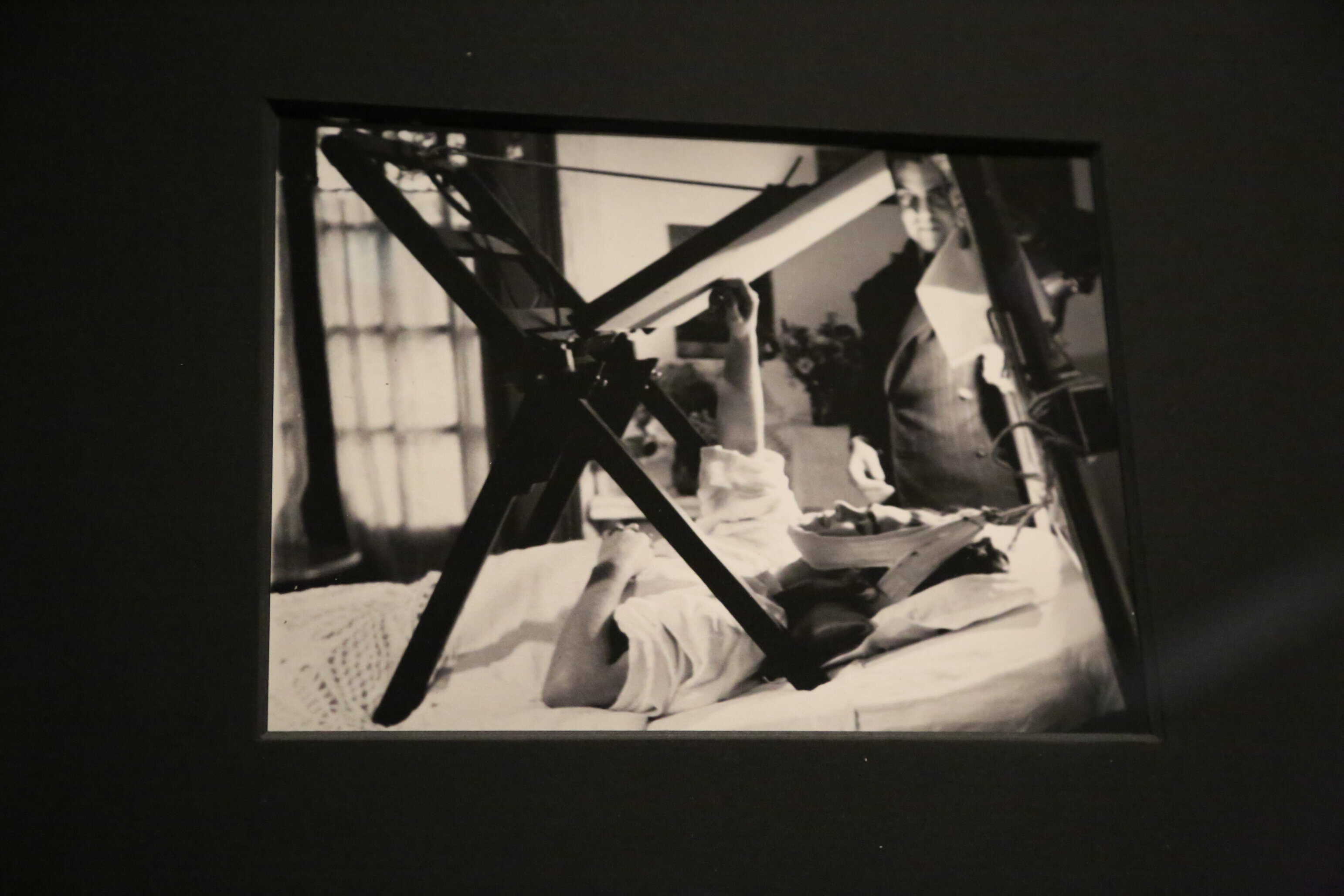

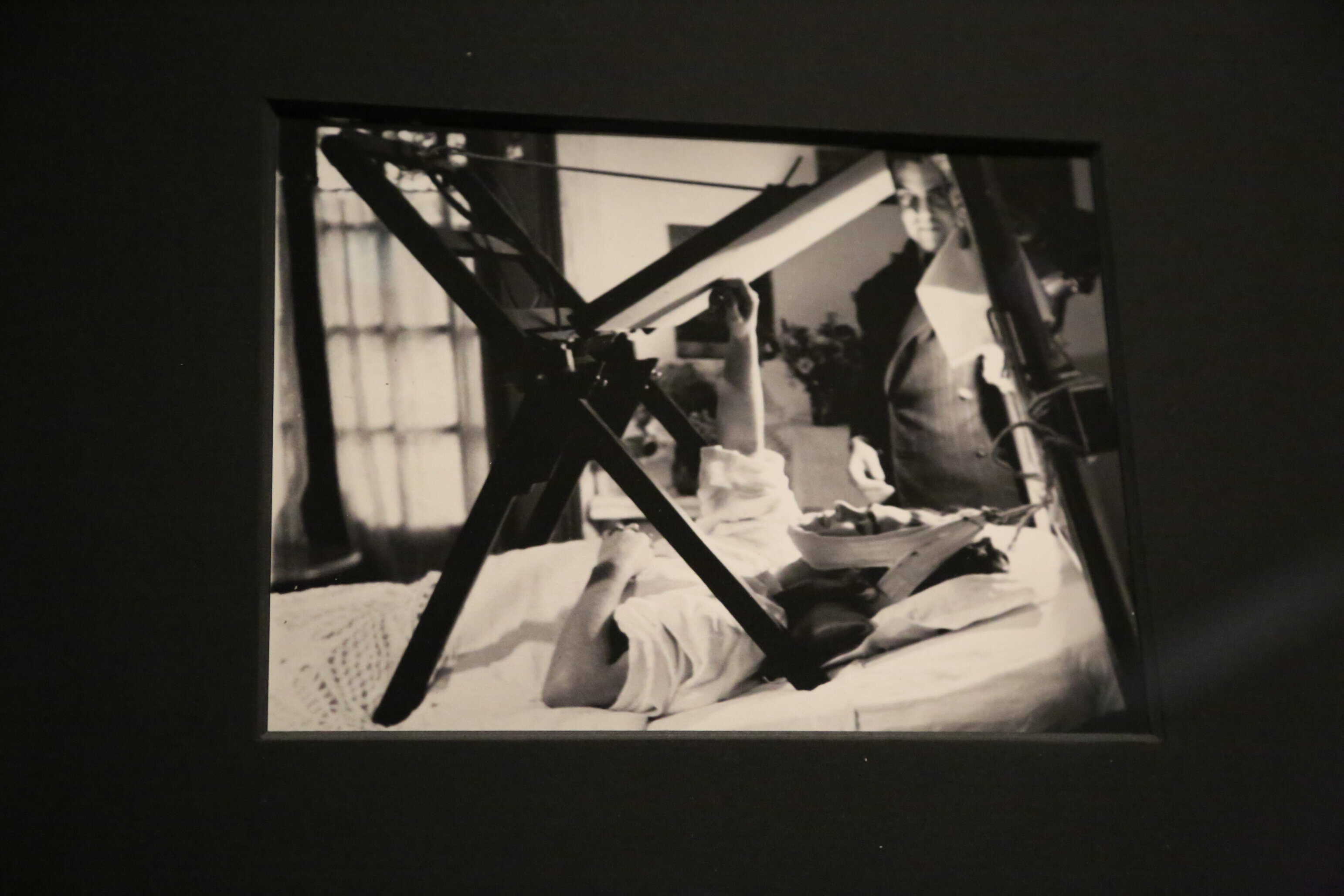

In the photograph of Frida Kahlo painting in bed, taken by Nickolas Muray in 1940, it shows the artist managing to paint, despite the challenges of being in traction.

The exhibition reveals through the juxtaposition of images and objects a visual narrative of the person behind the legend, to reveal the strength that the artist found within her circumstances to rise above her physical challenges, and to translate and transcend the pain through painting. She said: ‘I am not sick, I am broken. But I am happy to be alive as long as I can paint.’

The photograph above of Frida in her wheelchair was taken by Lola Alvarez Bravo in 1940, and above her bed portraits of revolutionary heroes are beside those of family and friends.

She endured numerous operations and wore a variety of orthopaedic corsets made of leather, steel and plaster, while complications resulting from polio meant that she had trouble walking, the the shoes needed to be built up to accommodate a shorter leg. However, she decorated and adorned her corsets, included them in her paintings to express her relationship them as one of support and need.

In conversation with IRK Magazine, Ana Baeza Ruiz, a member of the curatorial team, shared her unique perspective on the exhibition:

IRK: Its an inspiring exhibition in which Frida Kahlo is presented as one of the most recognised and significant artists of the 20th Century. It is an extremely up close, personal and immersive exhibition. Which period, artwork or room most interests you, and why?

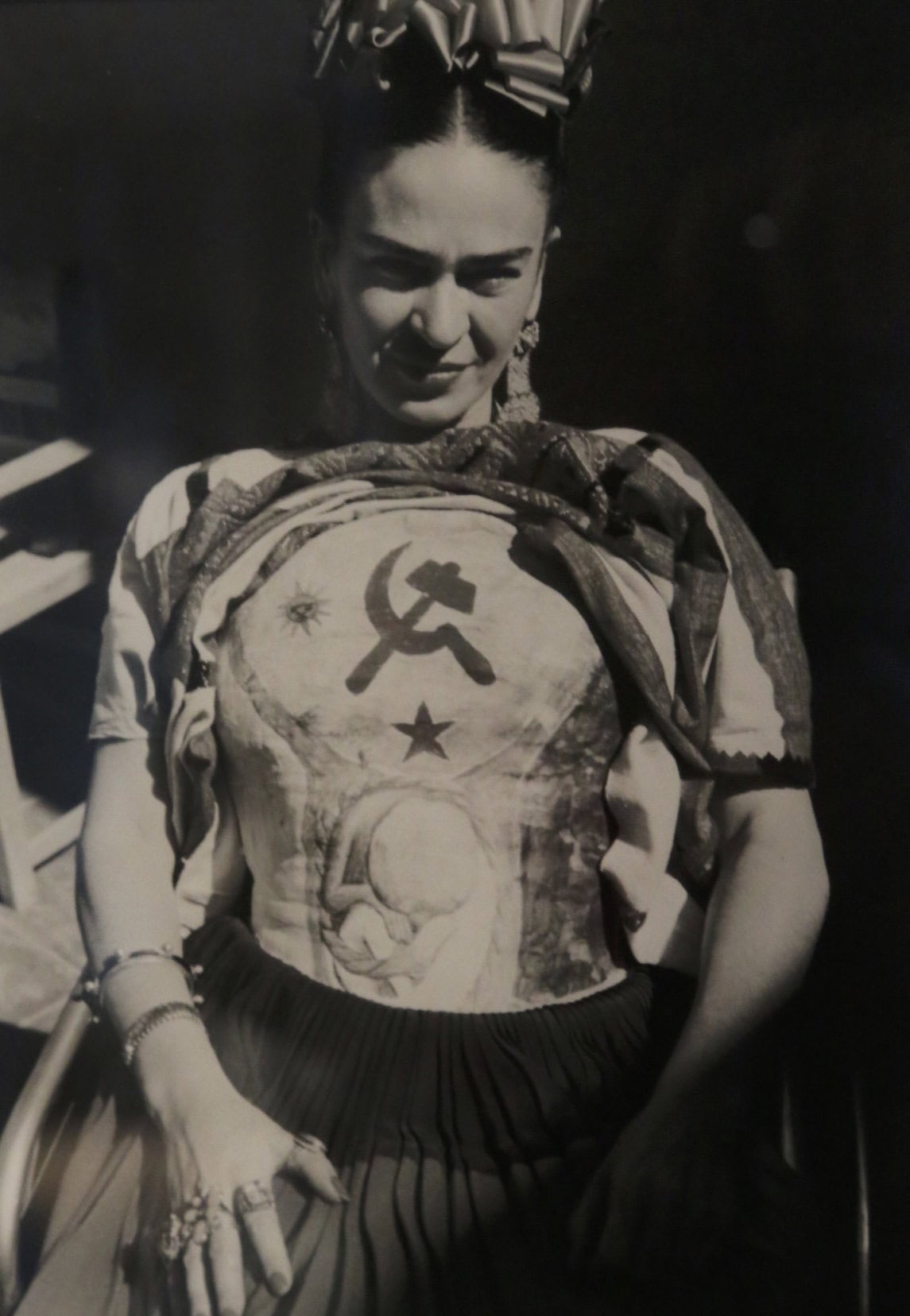

Ana Baeza Ruiz: I personally think that this room that we are in now, called ‘Endurance’, is the room that gets the closest to the artist. So we see these artefacts that speak about the difficulties and the struggles that she had to overcome as the result of the accident at the age of 18, but also the Polio that she had at the age of 6, that meant that her right leg didn’t develop in the same way as her left leg. But what we also see from the corsets at the back of the room, is how Frida Kahlo uses these objects also to transcend those issues caused by her physical condition. So she paints this one corset emblazoned with the hammer and sickle, showing her political commitment to communism, but also there is a drawing of a foetus, that recalls an academical model, as she had an interest in human anatomy and wanted to be a doctor as a child, but also she was not able to bear children as a result of that accident, she suffered. So we see that she is presenting this very difficult imagery, but also she is treating these objects as a canvas, and a second skin, that turned them into objects that generates a kind of sublimation also, of her experience. Also, another object I will draw attention to is the prosthetic leg that we see before us in this first case here. Her leg had to be amputated in 1953, so this was the last year of her life. Yet again there is a boot that has tinkling bells, that has Chinese motifs, so she is embracing these objects and making them part of her wardrobe. So this gallery in a way shows us how significant to the wardrobe, these objects were, when we see in the next gallery when we see the full colour of these costumes, which is another wonderful gallery that I would like to mention, because it shows that political allegiance to Mexico, to her roots and her heritage in the form of the Enagua dress that she adopted, and she is known for.

Frida Kahlo is captured in the above photograph taken by Florence Arquin in 1951 revealing her adorned plaster corset, which is in the exhibition, and shown below.

IRK: You referred to the corset with the painted foetus, is also a reference to her miscarriages?

Ana Baeza Ruiz: Yes, well the corsets were painted later, in the 50’s, but gave reference to the miscarriages that she had in her life as a result of her accident.

IRK: Can you elaborate on the relationship she had with Tina Modotti, the great female photographer and political activist?

Ana Baeza Ruiz: So, Frida Kahlo met Rivera, her future husband through Tina Modotti in 1928 or so, and they became friends, for a long time, and they were part of the same circle, different artists, photographers, writers, that were part of a cultural renaissance in Mexico in the 1920’s, people that were interested in the cultural activity that was going on, and coming from the US and from Europe. Tina Modotti was also politically active, and they would have shared those beliefs.

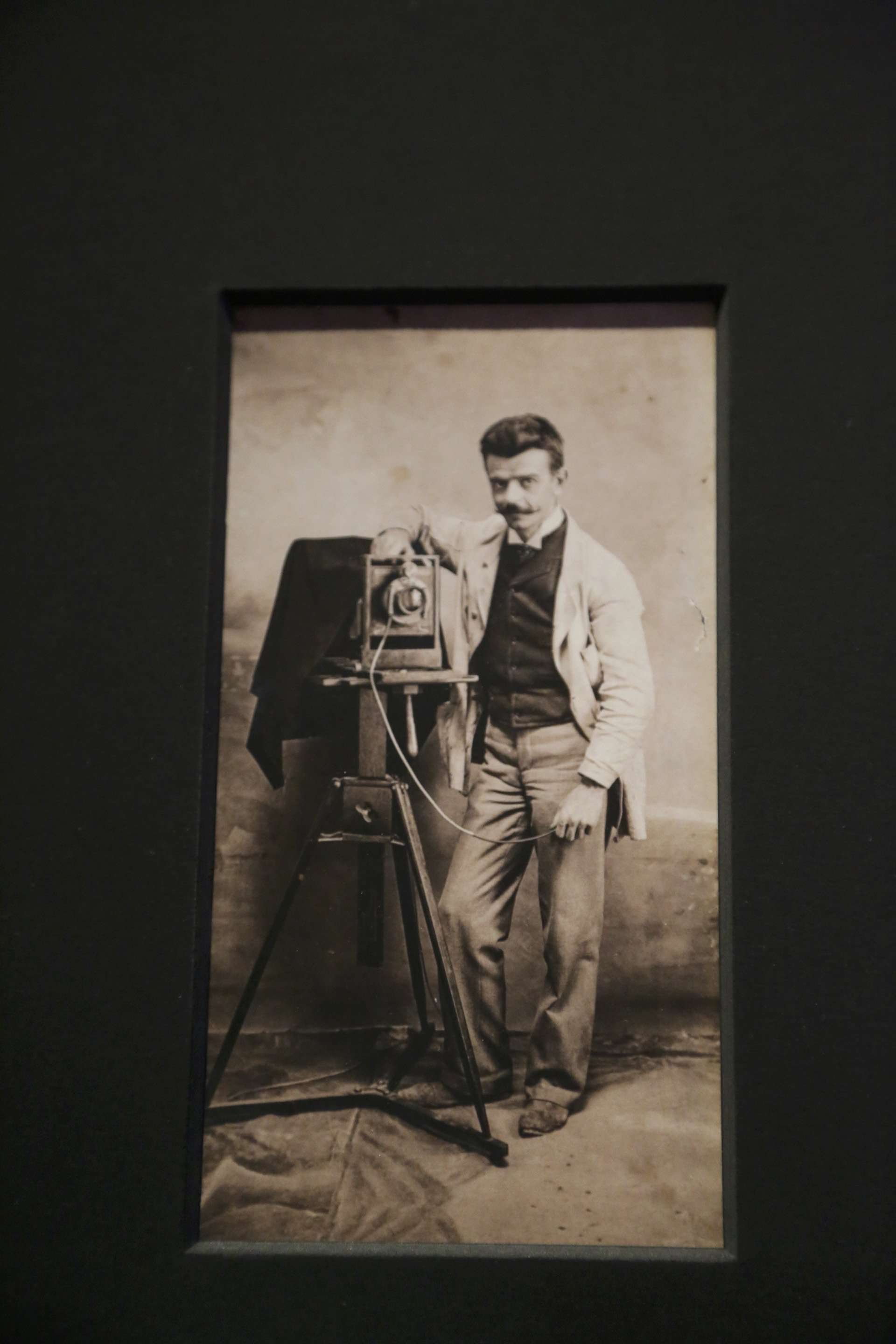

IRK: Did they also share a passion for photography? As the father of Frida Kahlo was the 1st official photographer of Mexico’s cultural patrimony in 1904, and Frida Kahlo was an accomplished photographer herself, with her father training her from a young age in the darkroom etc

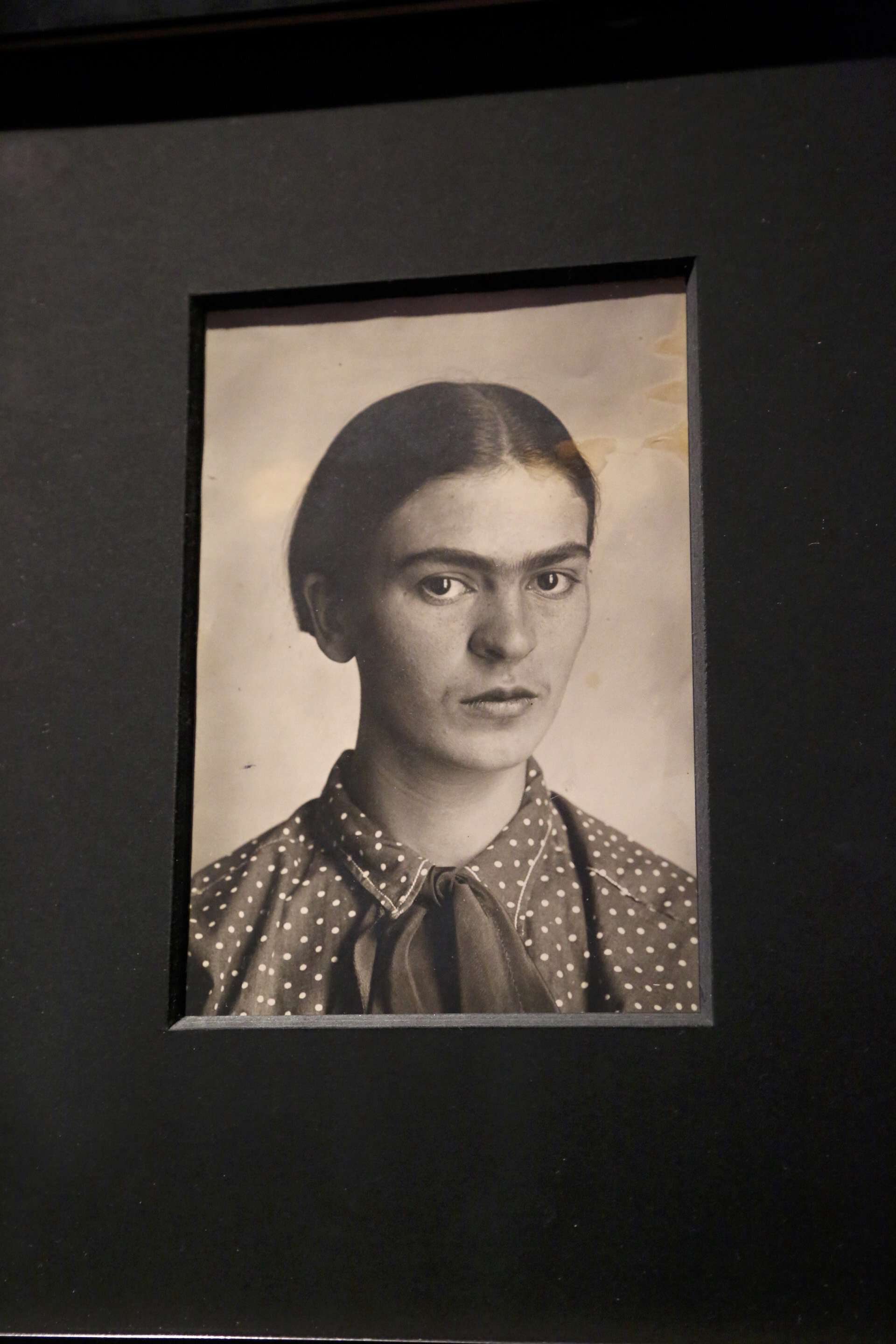

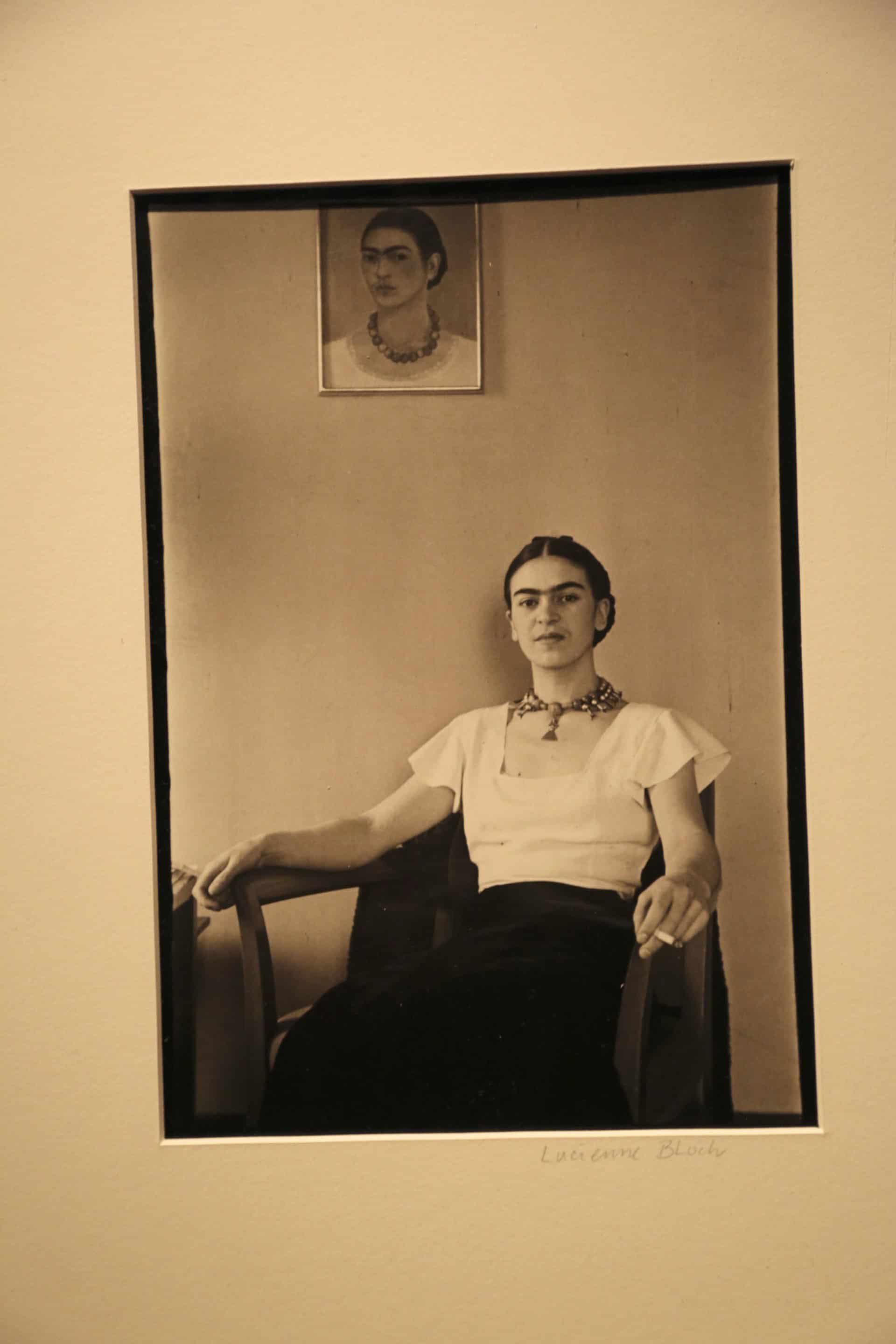

Ana Baeza Ruiz: Exactly, so she learned about the trade of photography from her father from a very young age, when she was accompanying her father, who also suffered from epilepsy, so he needed some assistance. She didn’t produce that much photography herself, but there are a few more abstract, still life’s that she did make, that are also in the collection of the Blue House, and we don’t have them in the exhibition. What is especially interesting is how she develops her relationship to the camera, how she is a subject, photographed by her father, and being a child she is becoming aware of that image that she then really crafts, and that is what we are dealing with in the show, her self image is produce through her choice of garments, through photography, and also self portraits, that we are showing in the exhibition.

IRK: The music is really haunting, and timelessly drifts in and out of consciousness, as if on anaesthetic. Was it composed for the show?

Ana Baeza Ruiz: Yes, the music was organised by the design team and the intention was that you have some birdsong when you come in to the Blue House, to allow us to reimagine that space, as we are not in Mexico here, so visitors cannot appreciate the place, which was so central to Frida Kahlo, because she lived there most of her life, and she was born there, and it was very much a site that showed her interest in her Mexican heritage, because of how she transformed it with Rivera, they paint it blue, have archeological artefacts in the garden, so that house is really important, and then we move into ‘Endurance’ which is muted sound, but it is also has, as you were describing, there is an element to it that leaves you wanting to really engage with these objects in the cases. There is a softness to it. Then you go into the final room. So definitely the soundscape of the final exhibition has been an integral part of the exhibition design.

IRK: When there is a threshold moment, a time of crisis in the life of the artist, of which Frida Kahlo had many, there is often a leap forward in the creative process of the artist.

Ana Baeza Ruiz: I think Frida Kahlo had an interest in art before the accident but I think that what the accident does do, is that it does create isolationism, and in ways we need to acknowledge that, but it also, because she is bed bound for months at a time, just after the accident, and there is a mirror inside the canopy of her bed, which she is able to see herself, and she starts to paint. So I think that there is an intensity to that moment, that is artistically expressed, and she starts to develop as an artist, but we can also say that prior to the accident there is a relationship to art, proved by the relationship with her father for example, that she is thinking about photography, thinking about her relationship to herself, and to her image, but I think that maybe that is accentuated afterwards

IRK: It is an extraordinary show, where the artists memorabilia are shown alongside her work, facilitating a forensic appraisal of the artist, and encouraging a deeper understanding of her creative process, character and personal narrative of her extreme medical challenges. What affect did handling the objects have on you and the construction of the exhibition?

Ana Baeza Ruiz: The objects arrived for the installation, but there were some members of the team that travelled to Mexico and saw some of the objects beforehand, and there has been a lot of thought going into the mount making so that these corsets especially, you would see them in the round, because they almost operate as a negative of the body of Frida, so having them in these beds, responds as much from trying to invoke that space of her in her disability, as much as it also allows you see these objects in the round, which is critical for understanding them, and for the visitor to engage with them.

These shoes had the front cut away to accommodate her gangrenous toes and the heal had been built-up to compensate for her shorter leg resulting from childhood polio.

The above necklace of milagros, traditionally left at a shrine or a church in prayer for a cure, features metal miracles constructed by the artist out of arms and feet may have been a reference to her childhood polio, that resulted in her emaciated right leg.

The necklace of black obsidian blades, was assembled by Frida Kahlo before 1942. Obsidian can be cut to create an extremely sharp edge, and the blades used were possibly part of ancient artefacts acquired by Rivera. The Maya had used such blades as weapons, and in this construction they are not drilled, but held in place by tightly bound red thread with a wire core. They symbolise her enduring strength to confront the adversity, pain and challenges of her life.

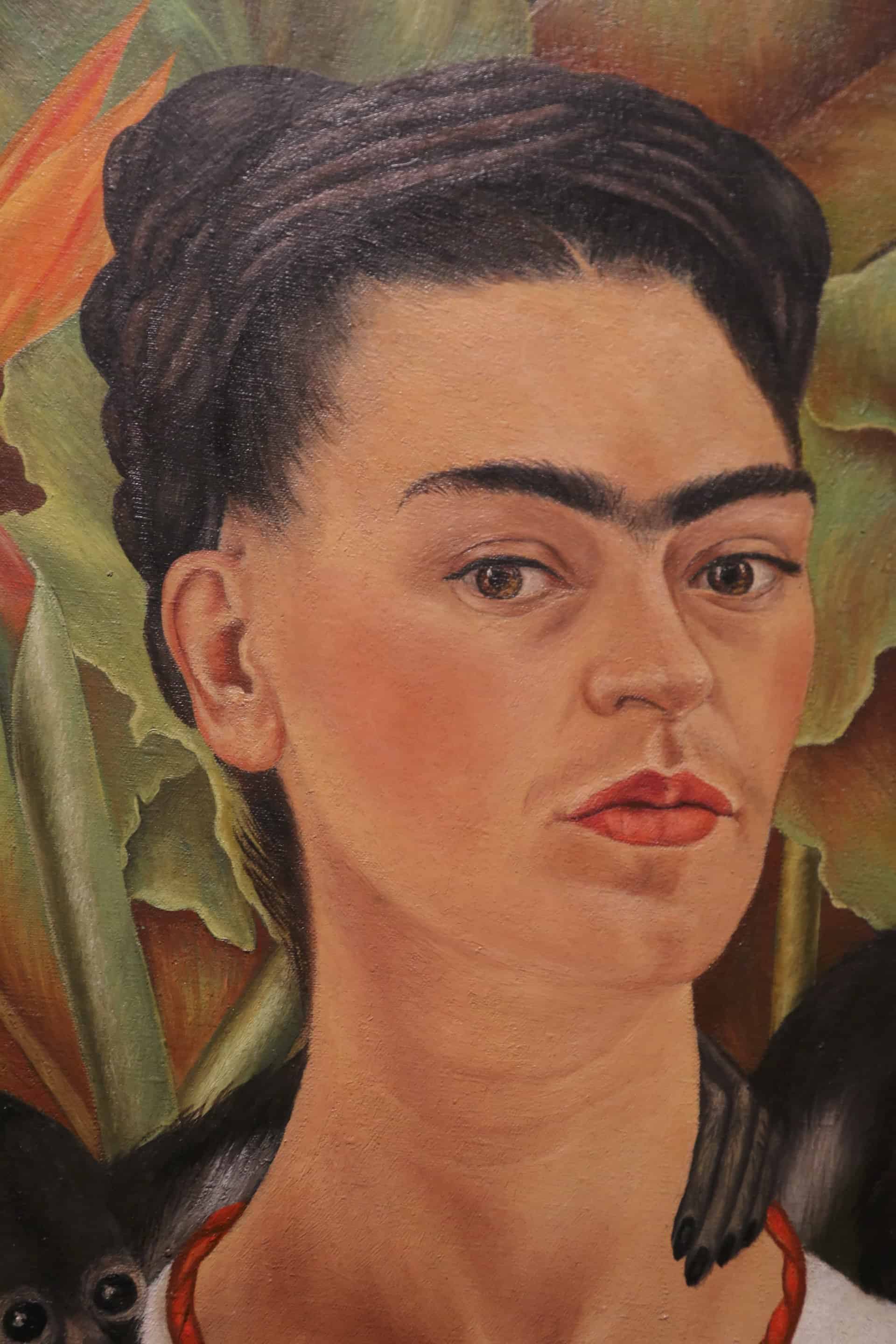

Frida Kahlo, 1943, Self-portrait with monkeys.

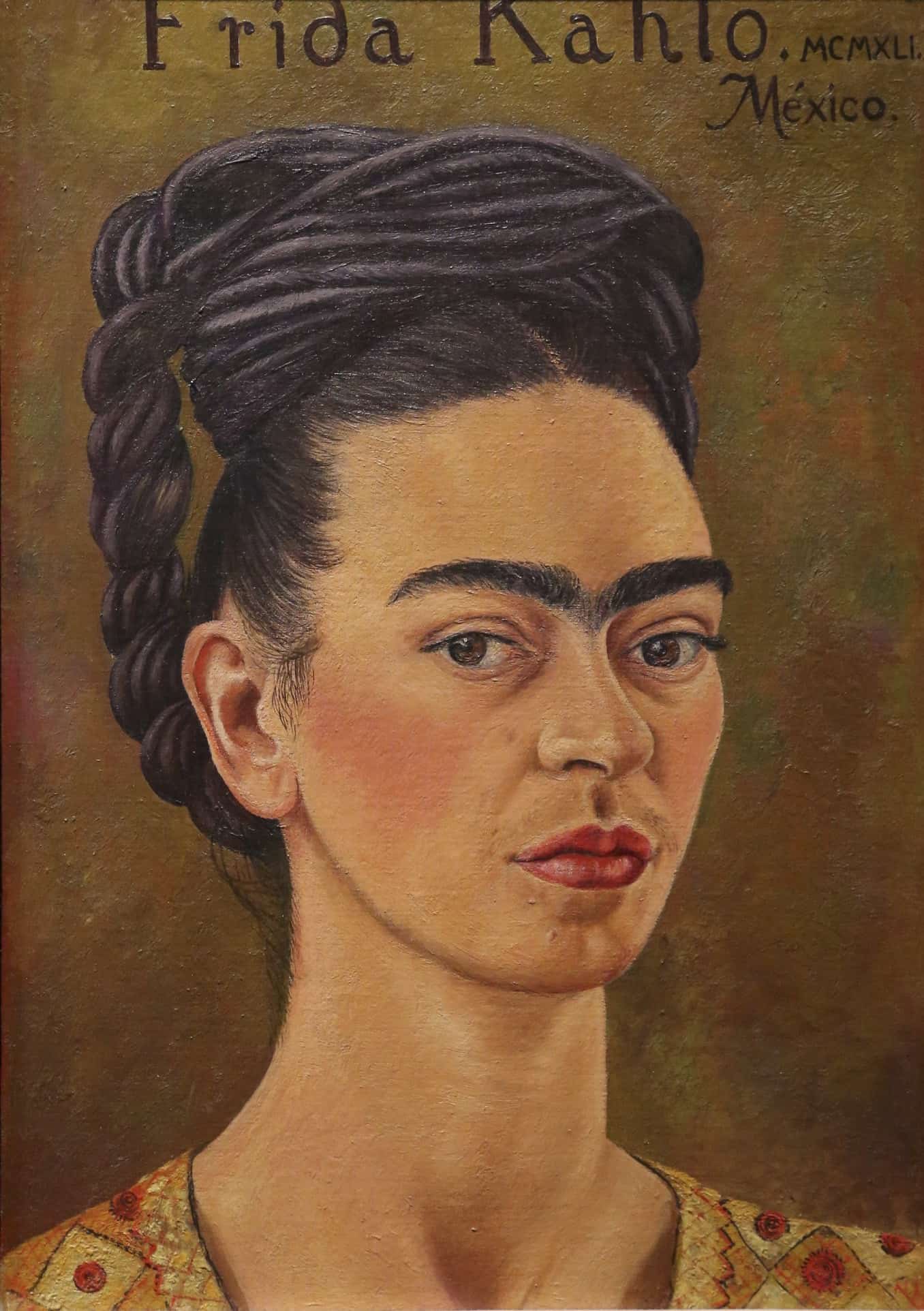

Frida Kahlo, 1941, Self-Portrait MCMXLI , painted after the death of her father.

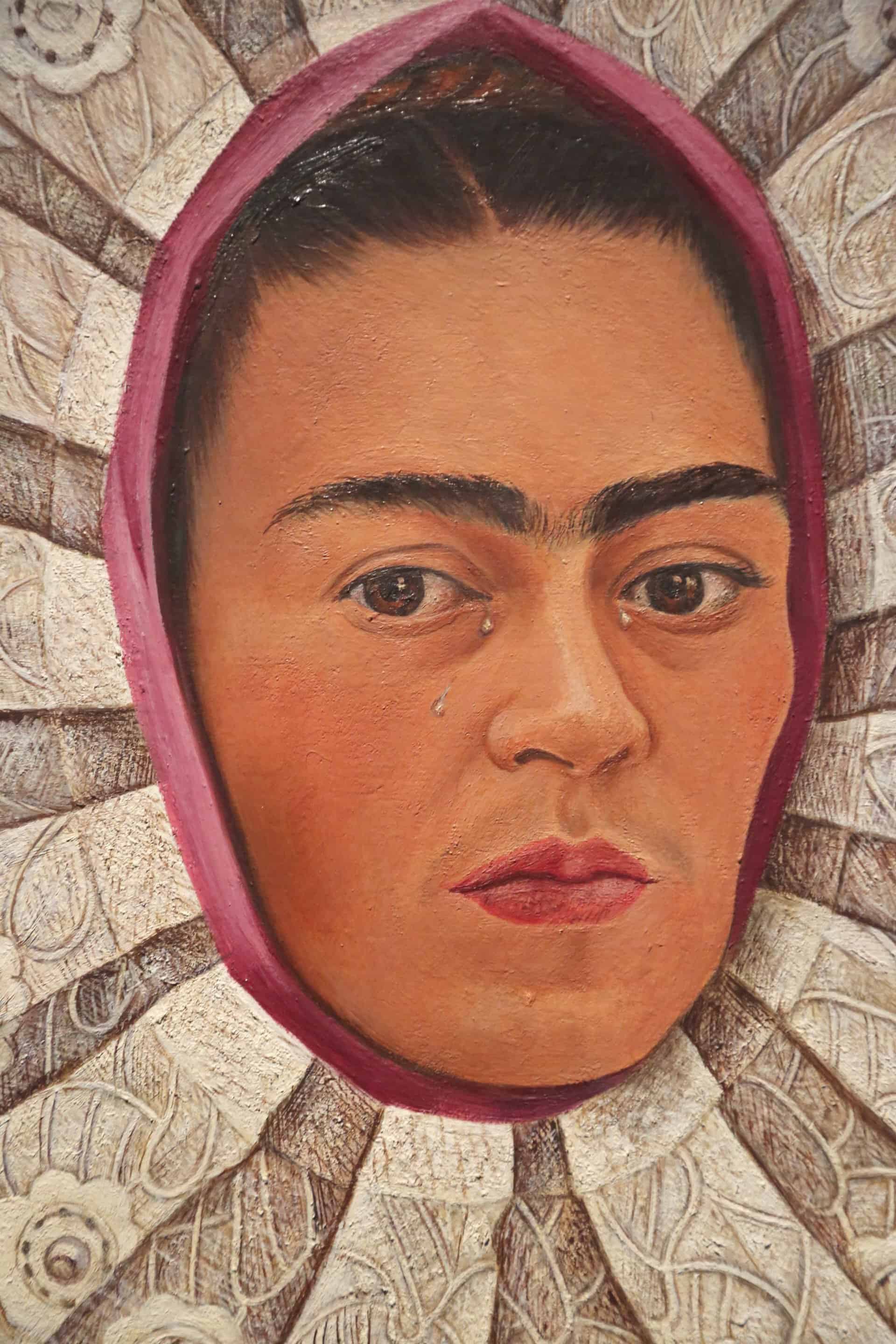

Frida Kahlo, 1948, Self-Portrait, displays Kahlo’s head peering from the pink opening of a Tehuana headers of starched, pleated lace.

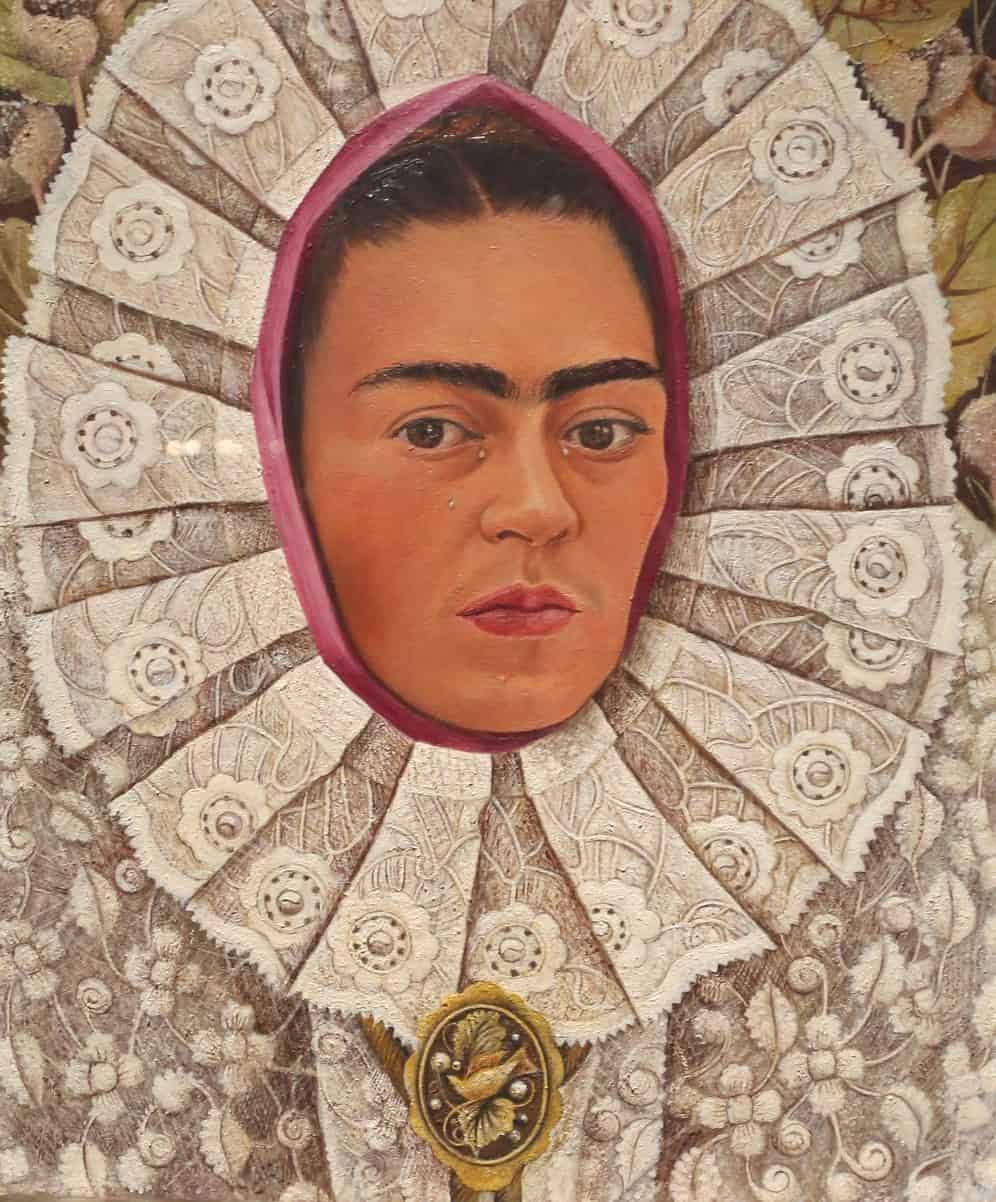

Frida Kahlo, 1943, Self-Portrait as a Tebuana’. Frida Kahlo depicts herself wearing a festive headdress of starched white lace, recalling the tradition of the ‘Crowned Nuns’, with Rivera’s portrait stamped upon her brow, like a spiritual wound.

Lace headdress and skirt from before 1954, Juchitan, Oaxaca, Mexico. The radiating headpieces are inspired by the statues of the Virgin Mary, and are worn by the women of Tehuantepec for church, weddings and processions.

To those who have health challenges, to those who may be tempted but unable to to visit this exhibition, I hope that this virtual visit may inspire the endurance to respond creatively to the individual circumstances in which they find themselves, and to gain strength from the inspirational life and work of Frida Kahlo,

Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up

Sponsored by Grosvenor Britain and Ireland

16 June – 4 November 2018

Victoria and Albert Museum

vam.ac.uk/FridaKahlo

Share this post

Natasha Hall is an internationally recognized British artist with a doctorate in Contemporary Landscape Painting. She has university qualifications in the arts and the sciences who specializes in interdisciplinary collaborations with scientists, artists and the wider community to realize her projects. Through constantly exploring the limits between the arts and the sciences, from documenting the reality of being a patient, the layering of landscape and the interaction of climate change with historical accounts…she has exhibited, organised conferences and continues to be represented by the Es Baluard Museum of Contemporary Art, the Gabriel Vanrell Art Gallery in Palma de Mallorca, and is delighted to be the European Arts Editor for IRK Magazine.

Read Next