Between Worlds with Barbara Cole

IRK Magazine

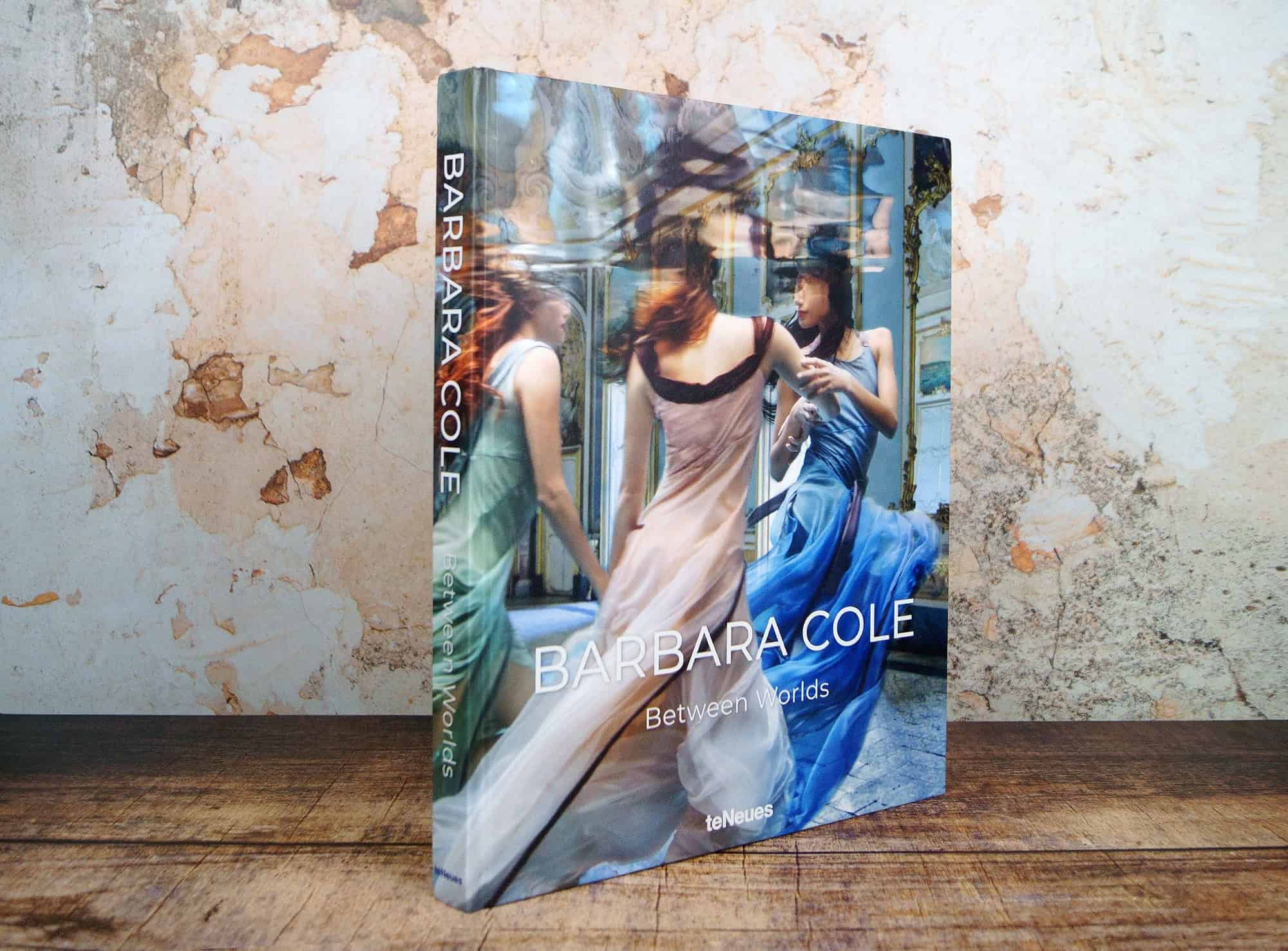

Barbara Cole’s book, “Between Worlds,” offers readers a profound dive into the intersection of art, emotion, and the ethereal qualities of underwater photography. Through this publication, Cole encapsulates over 35 years of her evolving artistry, presenting a collection that transcends time and medium. The book is a testament to Cole’s relentless pursuit of capturing the ephemeral beauty of figures submerged in water, showcasing a unique blend of photography and painting that invites viewers to explore their own imaginations. With contributions from the talented editor Josefine Raab, the book is organized in a non-linear fashion, providing a fresh perspective on Cole’s extensive catalog. Additionally, “Between Worlds” is enhanced with an interactive element featuring QR codes that unlock a deeper understanding of Cole’s work through videos, including behind-the-scenes glimpses, model interviews, and more.

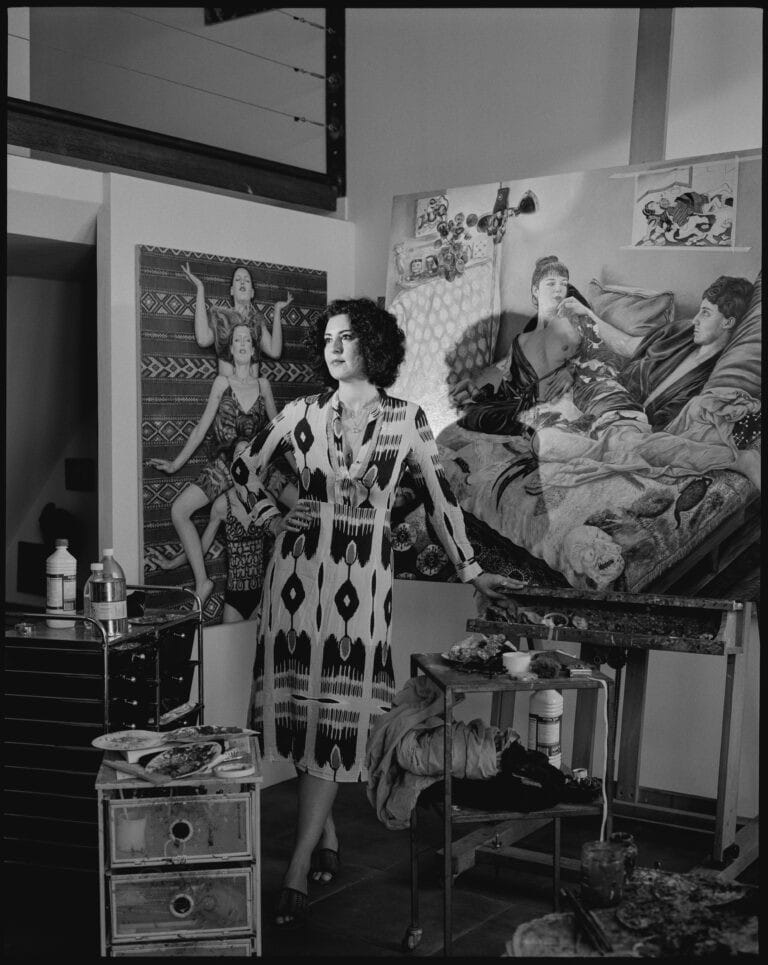

In the following interview, Cole is poised to share reflections on her creative process, offering a glimpse into the mind of an artist who has consistently pushed the boundaries of her medium. Join us as we explore the inspirations and aspirations that continue to drive her evocative exploration of the space between worlds.

Can you share the inspiration behind your latest art series and how it reflects your artistic evolution over the years?

When I began to take pictures underwater in 2002, the work was simply about the impressionistic way a figure would look in the water. I have never approached photographic artwork in a documented, realistic manner. That was why I worked for so many years using Polaroid films. I loved the way those films would render the figures as somewhat undefined, and that fit with my aesthetic. When Polaroid went out of business, I needed another manner of abstracting the body, and I decided that I would use water.

Over many years, I’ve reworked my water series using many different tools. In the series Falling Through Time, and now Somewhere, I am using the properties of water to define a figure, but other than that this photograph could be taken in a studio. The first impression is more of figures on a stage. It takes a bit of time to register that some things don’t quite add up because these bodies are underwater.

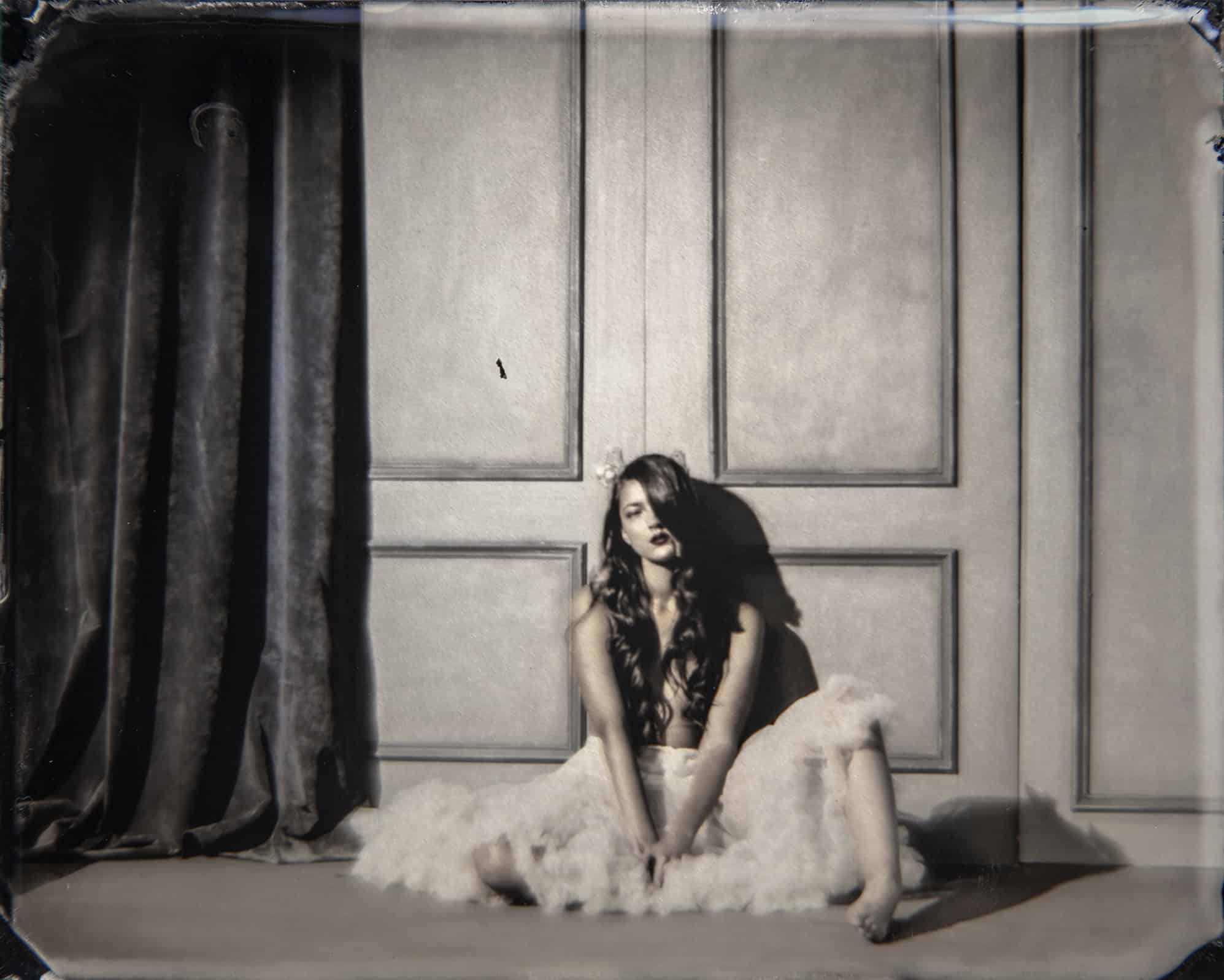

I have been shooting underwater for over 20 years, and I still love it very much. I live in Canada, however, and the weather is cold and snowy for about six months out of the year. I needed to find an inspiring way to shoot in the studio as well. I discovered wet collodion about 12 years ago, and it became my secondary outlet. I’m now working on a wonderful series that resembles early photography autochromes, and I’m feeling quite inspired.

Barbara, your work often involves underwater photography. What draws you to this medium, and how does it influence the emotions and themes you explore in your art?

I love exploring the figure in my practice. Working underwater allows me to focus on the altered reality of the submerged human form. It’s Instantly exciting to see the body moving in this sensuous, painterly, and idealized way.

I would say that I am a very private person, and art is a personal practice for me. Shooting underwater has allowed me the privacy to work without prying eyes monitoring instant captures on a screen. This appeals to me very much. Shooting has become a special experience between myself and the subject, and I have room to explore without intrusive commentary.

The final point I’d like to make is that working underwater is extremely calming. The sound is muted, and your body feels no gravity. I tend to be a depressive person, and working in this manner is quite therapeutic.

You recently published a beautiful book, Between Worlds. Tell us about the process of creating it. How long was the process, and what was your favorite part?

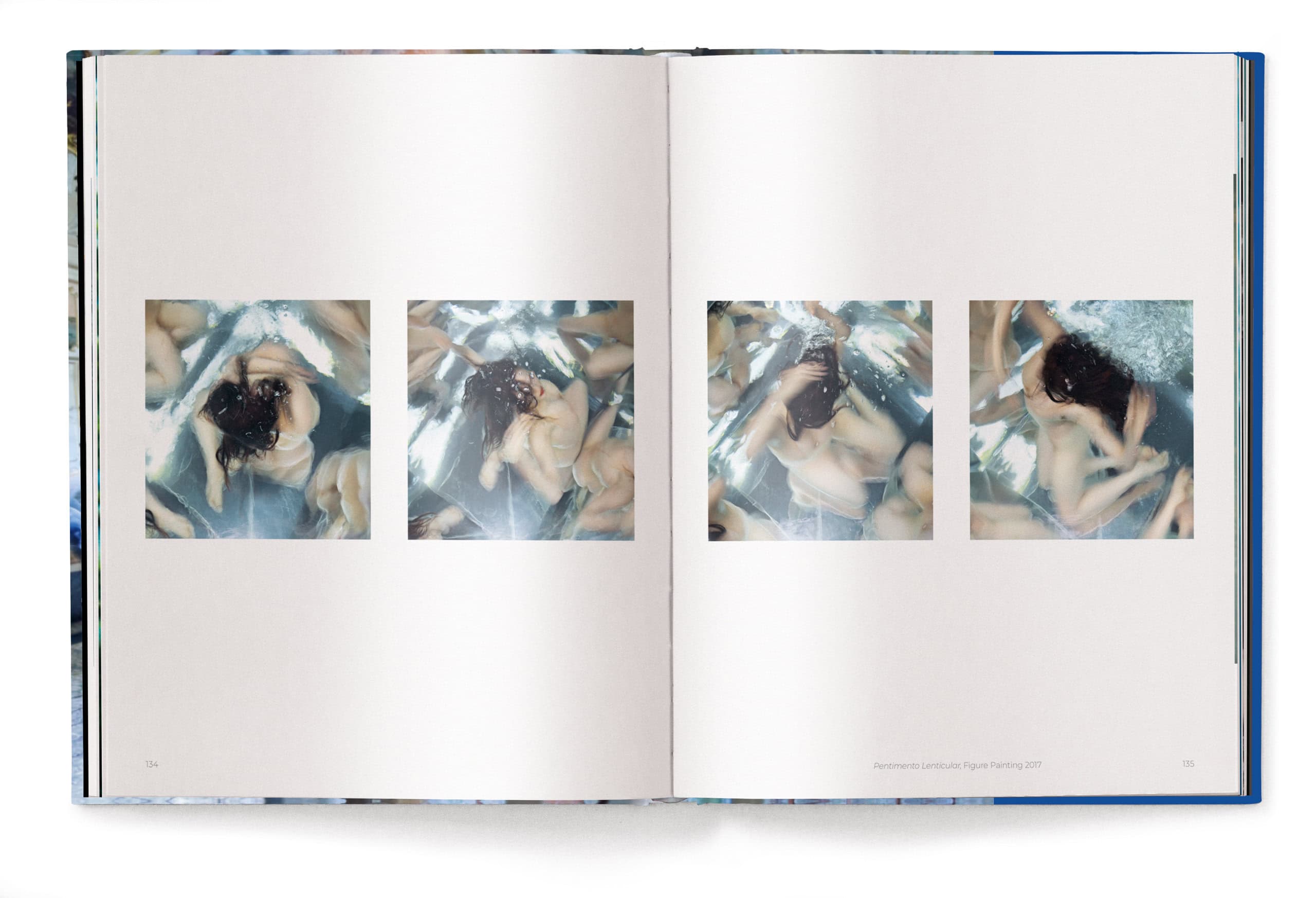

Between Worlds, published by teNeues in Germany, took about one and a half years to produce. In the beginning, the heavy lifting was on the artist, and in my case, I had to track down and scan my entire catalog. It was a little tedious, and what was so strange was that the book reflected over 35 years of work, yet while I was gathering the pictures together, I remembered the shoots as if they were yesterday. That was a lovely experience.

My favorite part was working with the gifted Josefine Raab, who edited and organized all the work. She treated it like a big puzzle and came up with a fabulous, non-chronological way of presenting everything. The day she sent the first pdf to me was an experience I’ll never forget!

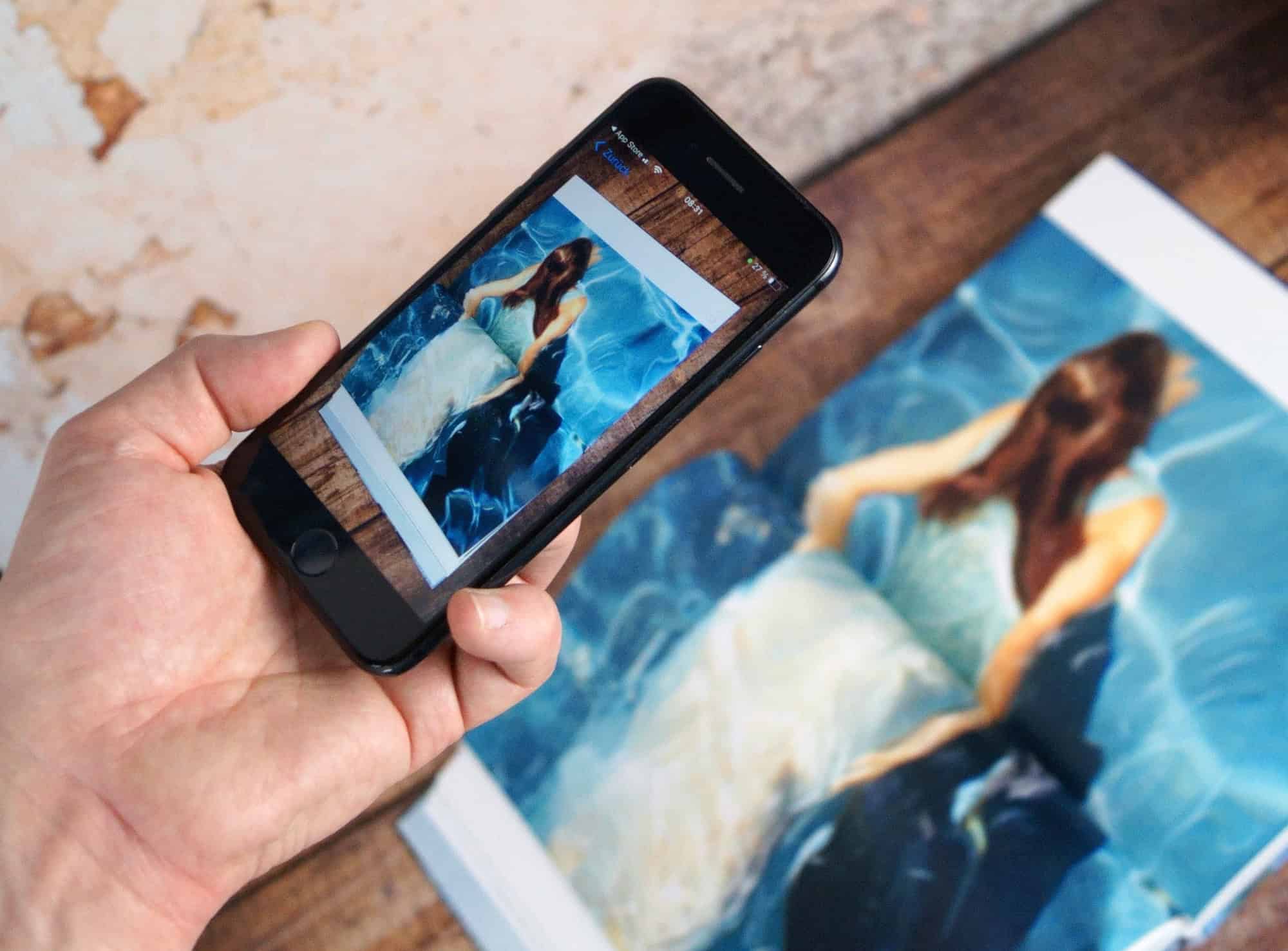

There is also a fun app that we’ve put into the book. My work is never what it seems, so I’ve made many videos over the years to allow my collectors some insight. There are QR codes in the book, so you are able to see many of the videos. It gives you a better perspective on each series if you would like more information. There are behind-the-scenes model interviews, installation views, and demonstrations.

Many of your pieces seem to capture a sense of ethereality and surrealism. How do you approach the process of translating abstract concepts into visual forms?

While I agree there is a sense of surrealism and ethereality, it’s not intentional most of the time. I believe it’s just the way I feel like creating that image. I trust my instincts about this, even though I may not understand why I’m doing it.

What music or art inspires you before you prepare to shoot underwater?

If I’m perfectly honest, I’d have to say silence is my inspiration before a shoot. In the studio, during shoots, I play music for the crew, but if I had my choice, I would work in silence. Oddly, music blocks out my inner voice and always has. I was never one of those teenagers who did their homework with headphones playing music.

Your use of color is striking and plays a significant role in your art. Could you elaborate on your color choices and how they contribute to the narrative or atmosphere of your pieces?

American fashion designer Isaac Mizrahi once said, “If you get the color right, you’ve got everything,” and I totally agree. I spend a lot of time choosing my color palette before I begin a series. The costume needs to work with the background and in relation to other costumes or props. I think of it as a stage set…the moment the curtain goes up and the audience lets out that sigh.

Once you’ve put clothing underwater, it is yours, so renting is out of the question. I came to the conclusion that instead of buying readymade clothes, I would work with a designer, cutter, and stylist to create exactly what I wanted. I was a fashion editor for ten years before I became a photographer, so this is familiar territory, and I quite enjoy it.

There is usually a graphic pattern that I like or a set of colors I tend to love, but it’s all very specifically coordinated before the series begins.

Collaboration is a recurring theme in your career, working with dancers and other artists. How do these collaborations enhance your creative process, and what unique perspectives do they bring to your work?

I think it’s terrific to bring other talents into your project because it keeps the energy flowing. The important point is that I must have a specific vision that people are riffing off of. Otherwise, there is a chance that the work won’t have your specific signature on it.

So many talents out there—be it hair or makeup or stylists—are in the day-to-day world of commercial photography. That isn’t why they decided to work in their field, though. As an artist, I am able to provide a more creative space for them to get involved.

Robert Danes made you some custom gowns to shoot with. Talk about that process and what it was like preparing to shoot his gowns underwater.

Robert Danes and I had worked together on a couple of smaller projects, but I always tagged him in the back of my mind as the designer for Somewhere. When I got the confidence to ask him, Robert was very excited and, if I’m totally honest, a bit nervous about creating dresses underwater. It was a new challenge, and we were both excited to see what would happen.

Robert and I had a couple of discussions on Zoom, and my favorite part was when he began sketching as I spoke. I felt he immediately understood not only the silhouette of the dresses but the color palette of the shoot. When the dresses arrived, they were almost too beautiful to get wet! I used them for the first part of my shoot. I then sent them back to Robert to change up a couple of details so they would be slightly different for the remainder of the shoot.

Barbara, you’ve exhibited your art internationally. How does the global context influence your creative expression, and how do different cultures respond to your work?

I’ve found that overall, the response to my work is the same whether I’m showing in Japan, Germany, the United States, or England. If you love the subject of water, the series is viewed favorably. I have noticed that the selection of favorites within a series often shifts.

In your earlier career, you worked extensively with alternative photographic processes. How have advancements in technology influenced your artistic practice, and do you still incorporate traditional techniques into your work?

When I first became a photographer in the 1970s, I worked in traditional analog processes. I would push black-and-white film for grain, make prints, and then hand-color and applique them. I only began doing alternative processes about ten years ago. I believe it was a reaction to digital photography and how easy things had become. The act of taking a photograph stopped feeling personal. I wasn’t creating pictures as much as out-putting them.

In response, I turned to wet collodion photography, which is the earliest form of photography, and it requires diligence and technical skill. I had missed that part of taking pictures. It has been full of frustrations and troubleshooting, but I love the challenge. It’s taken a while, but I now feel like I understand its language. I love being so grounded and hands-on. The pictures are like no other. At the moment, I’m trying to modernize the look and create something brand new.

The theme of transformation and metamorphosis is evident in many of your series. Could you delve into the symbolism behind these themes and what they mean to you personally?

I think it’s very important to continue to grow personally. I try to apply that idea conceptually as well. I don’t see any point in doing the same thing over and over again artistically. Every series pushes the medium a bit further down an imaginary line.

It’s not a conscious thing, but the symbolism is probably a visual record of the transformations that are going on inside my head.

Your art has been described as a blend of photography and painting. How do you navigate the boundaries between these mediums, and what unique qualities does this fusion bring to your creations?

I love to create anonymous images so that all the viewers might be able to imagine themselves in my world. That is one big reason that I shoot with abstraction in mind. I will slow my shutter to create a figure blur, or I might deliberately shoot out of focus. Often, I crop off partial heads or turn the face away from the viewer.

As I’ve already said, I’m not a fan of realism in photography. I want to be able to tell a vague story in a painterly way in order to lead the viewer back into their imaginations. I want to provide a preliminary outline of the story, but I don’t want to give the ending away. That’s for the viewer to decide.

Barbara, you have a distinctive style that has evolved throughout your career. How do you balance staying true to your artistic identity while also pushing the boundaries of your own creativity?

There is a very simple answer to that question: I don’t know how to do it any other way!

You’re celebrating the female form in your art. Is this something that has always been important to you?

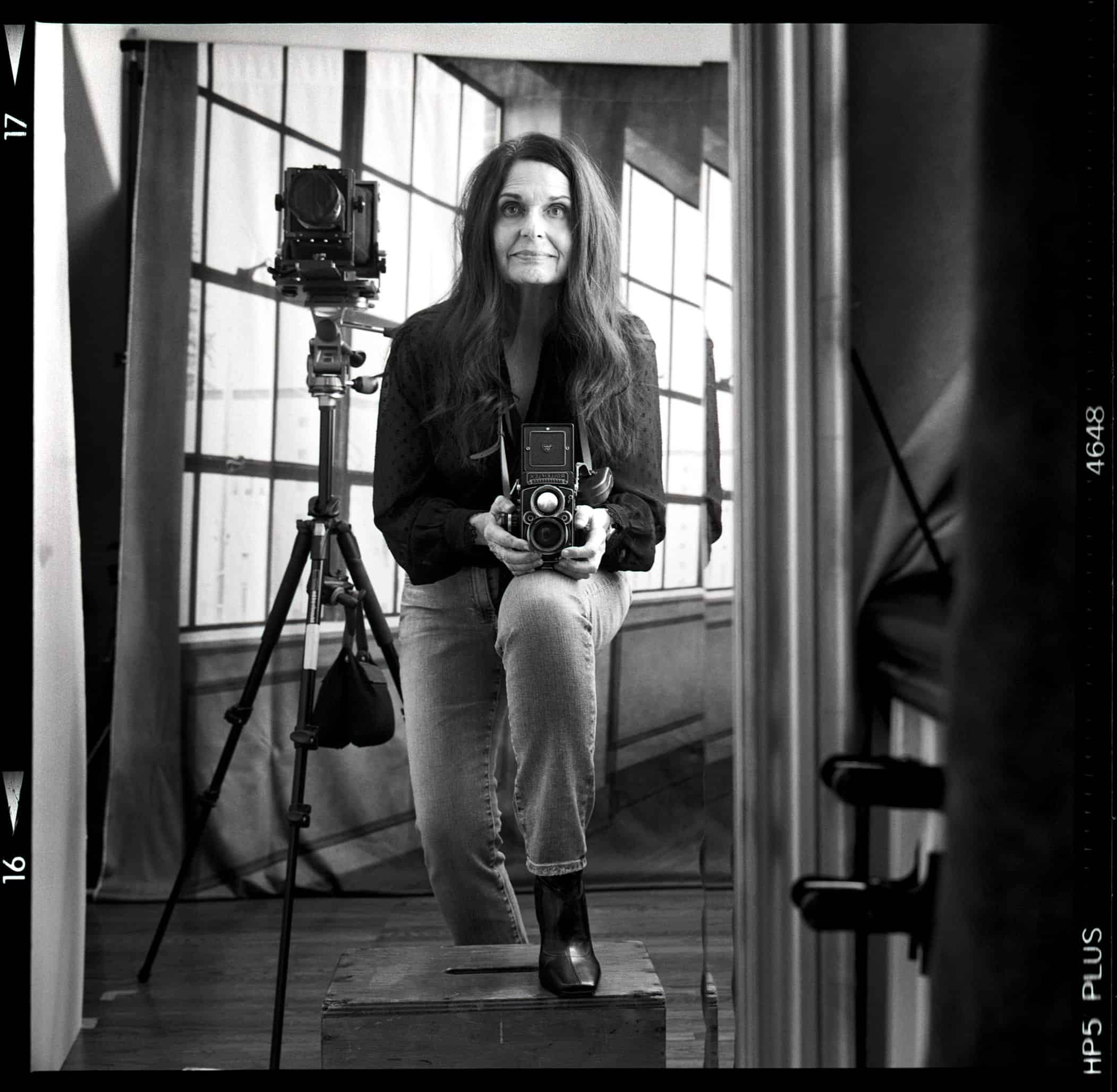

When I started shooting, there were not a lot of female photographers out there. Male photographers tended to objectify women in their pictures. I felt it was very important to render the female figure from a woman’s point of view. I’m not sure how that is different, but I feel that it is. I try to show a woman’s beauty without sexualizing it.

While creating your art, how much is the reaction of the audience in your mind? Do you focus on that while shooting?

If I’m being honest, I have to say I am at least aware of the audience’s reaction. Does that prevent me from creating a body of work? No, not really.

Do you plan to do more photo books in the future? What are some creative aspirations for 2024?

I would love to do a book of my studio work at some time in the next ten years, but at the moment, I’m still trying to appreciate Between Worlds. It was a great experience to produce, and my team was fantastic. Especially Stefan Brecht, who brought my work to the attention of teNeues.

Coming up for 2024, I am working on an ambrotype project; the working title is Fragments. I will also be testing out a new idea in the water come springtime. Lots of fun, interesting, and creative things floating around in the air and the water!

Share this post