Charles Brooks Inside the Secret Cathedrals of Sound

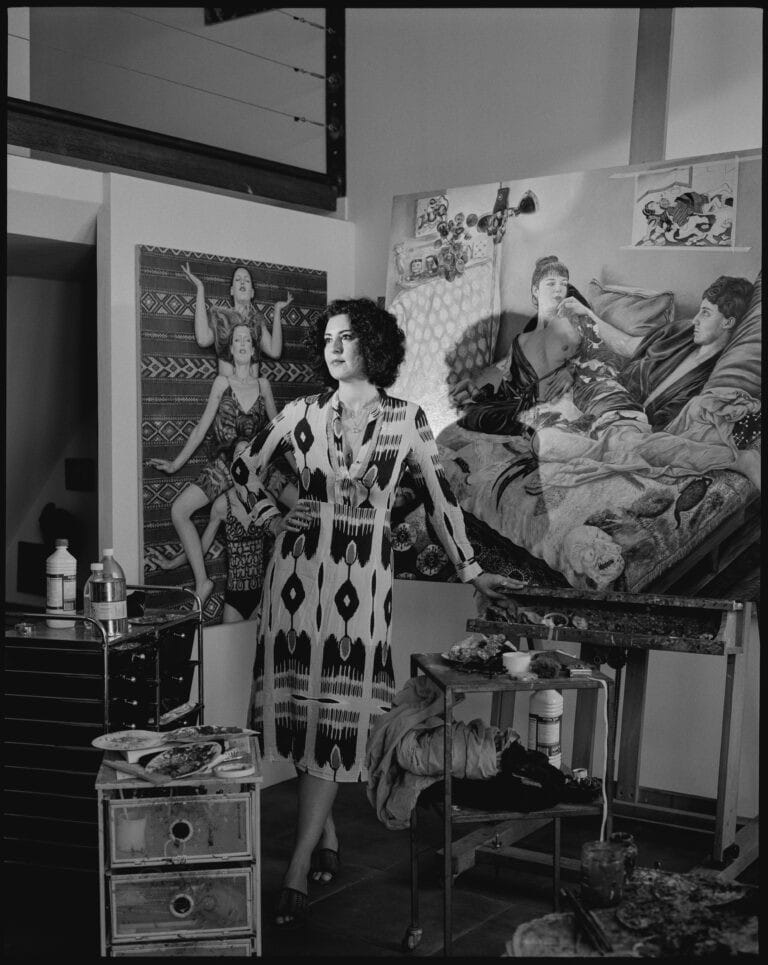

Agnese La Spisa

The Extraordinary Photography of Charles Brooks

If you’ve ever wondered what a Stradivarius looks like on the inside, Charles Brooks is the man who shows you. The New Zealand–born cellist turned photographer has spent the last several years crawling inside some of the world’s most precious instruments. He uses cameras so small they barely qualify as cameras anymore. And the results? Pure magic. Viral magic. Sixteen million views kind of magic.

Brooks didn’t arrive here by accident. Before becoming one of the most widely published photographers on Earth, he spent over 20 years as a professional cellist. He performed as principal in orchestras across China, Chile, and Brazil. So when he photographs the interior of a cello, trombone, or Steinway action, he’s not just snapping a picture. He’s documenting a world he understands on the molecular level.

His “Architecture in Music” series has appeared everywhere from Australian Geographic to Der Spiegel. And while most of us look at an instrument and think, “Wow, pretty,” Brooks looks at it and thinks, “Let me climb inside this thing and uncover the history carved into its ribs.”

Below, he walks us through the archaeology of instruments, opening doors to a universe most of us never knew existed.

Your images reveal the inner architecture of instruments as if they were cathedrals or vast landscapes. When you look inside an instrument, what are you searching for, structure, emotion, memory, or something else entirely?

I am always looking for structure and history. The exterior of an instrument is usually so refined that it can feel almost anonymous. But inside you can see the hand of the maker and the entire life it has lived. You see tool marks from the workshop of a craftsperson who may have been working four hundred years ago. You see repairs, patches, oxidation, and all the signs of music passing through it for decades or centuries.

I love instruments that have been heavily repaired because they develop a character that feels like an old leather coat. This coat has perfectly moulded to its owner. That sense of wear and memory gives me a far deeper connection to the full story of the instrument.

After a 20 year career as a professional cellist, how does your musical intuition guide the way you frame, light, and interpret the internal world of these instruments?

These images demand a level of patience that feels very close to practicing the cello. The physical sensitivity of the instruments guides almost every technical decision I make. Many of them react dramatically to temperature changes. Thus, I have to think carefully about how I place lights and how much power I use. My musical background helps me understand the limits of what is safe. The process itself can take many hours as I shoot frame after frame, shifting position one millimetre at a time. It becomes meditative, like a scale.

When I work with an instrument that is particularly old or valuable, that knowledge encourages me to frame and light the space in a way that feels worthy of its history. The aim is to reveal an internal world that has the same sense of grandeur I felt as a performer playing alongside it on stage.

The precision and scale inside your photographs feel almost surreal. Can you walk us through the technical journey, from gaining access to rare instruments to achieving that immersive, architectural perspective?

Sometimes the journey begins years before I ever touch a camera. To photograph something like a twenty million dollar Stradivarius you first have to earn the trust of the owner, the musician, and the institution that cares for it. That takes negotiation, planning, insurance, and a lot of relationship building.

Once the instrument is finally in front of me the rest is a careful exercise in visual engineering. It’s a carefully crafted optical illusion. There are a few cues that tell the brain when something is small, even if it fills a wall. Depth of field is one. When you look at something tiny up close, the background melts into a blur. My lenses behave the same way. They are only four millimetres wide, which means they can reach tiny spaces, but they cannot produce much depth. To counter that I use focus stacking, often thousands of frames, to keep the entire scene sharp. I also shoot with very wide angles and usually create panoramas. The back of a violin can be much smaller in the stitched image than the area close to the lens. So objects shrink faster than in normal life.

Finally I light the scene as if it were illuminated by the sun so the viewer instinctively feels as if they are standing inside a real place. When all these elements combine you end up with a delightful cognitive dissonance. Your eyes know it is small while your brain insists it is vast.

Every instrument has a life, performers who played it, rooms it resonated in, years of vibration soaked into its structure. How do you translate these invisible histories into a visual narrative?

Some instruments show their history very clearly. A brass instrument, for example, might have layers of oxidation that have built up from every breath of every rehearsal and performance. Those molecules fuse with the metal over time and leave behind a record of the music that shaped it. When you magnify these surfaces they become landscapes of memory. String instruments reveal their past in different ways. You see it in the repairs, in the tiny cleats and patches that luthiers have added over centuries.

But it is not only old instruments that hold interest. New ones can be just as striking. The precision inside a Steinway or Fazioli action, with more than eleven thousand parts, or the fine machining marks on a brand new saxophone, can be just as compelling. Each one tells a story, whether that story spans three hundred years or three months.

Your series has appeared everywhere from Australian Geographic to Der Spiegel. Why do you think these images resonate so widely, and what conversations do you hope they spark about craftsmanship, music, and perception?

I think people are fascinated when they are shown something familiar in a completely new way. Everyone knows what the outside of a violin looks like, but very few people have seen the world inside it. When you reveal the age, the wear, and the sheer amount of human touch that has passed through an instrument, people pause. They think about music, memory, their favourite concerto, or the artist they love. They imagine sound echoing through the wooden walls they are staring at.

These photos speak to both sight and memory, and that combination can be surprisingly powerful. I hope they spark curiosity about craftsmanship and remind people that instruments are living artefacts shaped by generations of hands and voices.

Your work has expanded beyond instruments into scientific environments like particle accelerators. How is your curiosity shaping the next phase of your explorations?

I have not photographed the Large Hadron Collider yet, but I have photographed a smaller particle accelerator in Melbourne that still takes up an entire city block (the Australian Synchrotron). It was thrilling, especially when the physicists explained that its manipulation of light is not far from the way a flute manipulates sound, just on a scale that is unimaginably fast. I am also experimenting with ways to merge my macro work with my astrophotography. This creates some very exciting connections between the smallest and largest structures we can see. But no matter where I go, there will always be more instruments to explore. Each one is unique so I expect this series will continue for the rest of my life.

If Brooks has taught us anything, it’s that the world is full of hidden architecture. Inside instruments, inside machines, probably even inside that flute you haven’t practiced since middle school. His curiosity doesn’t seem to have an off switch, and thank goodness for that. Wherever he points his camera next, we can count on one thing: he’ll make the invisible look spectacular, and he’ll make us wonder what else we’ve been missing.

Share this post

Agnese La Spisa is an Italian creative based in Italy, specializing in publishing and fashion communication. At IRK Magazine, she brings together creativity, research, and design to shape stories with clarity and style. Curious and collaborative, she is driven by a passion for exploring culture, aesthetics, and the narratives that connect people, ideas, and disciplines.

Read Next