FATEN GADDES TURNING SILENCE INTO ART

Brendan Cannon

Faten Gaddes: A Multidisciplinary Voice Rooted in Memory

Faten Gaddes is a French-Tunisian visual artist based in New York. Trained as an interior architect, she has developed a multidisciplinary practice that spans photography, design, fashion, scenography, and culinary arts. Initially working in architecture and design, she soon turned to photography, her true passion, which became the foundation of a broader, politically engaged artistic journey.

Her work is deeply rooted in memory and personal history, often addressing themes of identity, exile, violence and resilience. Through installations, sculptural forms, and documentary images, she reconstructs silenced or erased narratives, especially those tied to women’s bodies and lived experiences.

HALWA: From Destruction to Creation

Faten is the creator of HALWA, a multimedia and politically charged project that originated after the destruction of one of her early installation PUNCHING-BALL in Tunisia. The project explores trauma, reconstruction, and the tension between imposed aesthetic norms and artistic freedom. Currently, she is preparing a solo exhibition of HALWA in New York.

She is also developing Itinerary, a photographic and film-based project created in collaboration with Native American communities in the U.S, exploring themes of heritage, transmission, and healing.

Wearable Narratives: Merging Fashion and Photography

In parallel, Faten is expanding her creative expression through fashion and culinary storytelling. She is currently working on a capsule collection of silk dresses featuring her own photographic prints—merging body, memory, and image into wearable narratives. One of her signature pieces, the Didon dress, evokes ancestral strength and the mythology of resistance.

Her passion for food as a medium of cultural transmission has led her to design immersive events, including a culinary workshop and dinner at Atelier Jolie in collaboration with Eat of Beat, where she introduced Tunisian flavors and rituals in a performative, community-centered format. This is how Couscous by Didon was born, a project that fuses culinary heritage and artistic gesture. It is a culinary art project through which she curates private dinners and intimate events, blending Tunisian flavors with visual storytelling, scenography, and cultural memory.

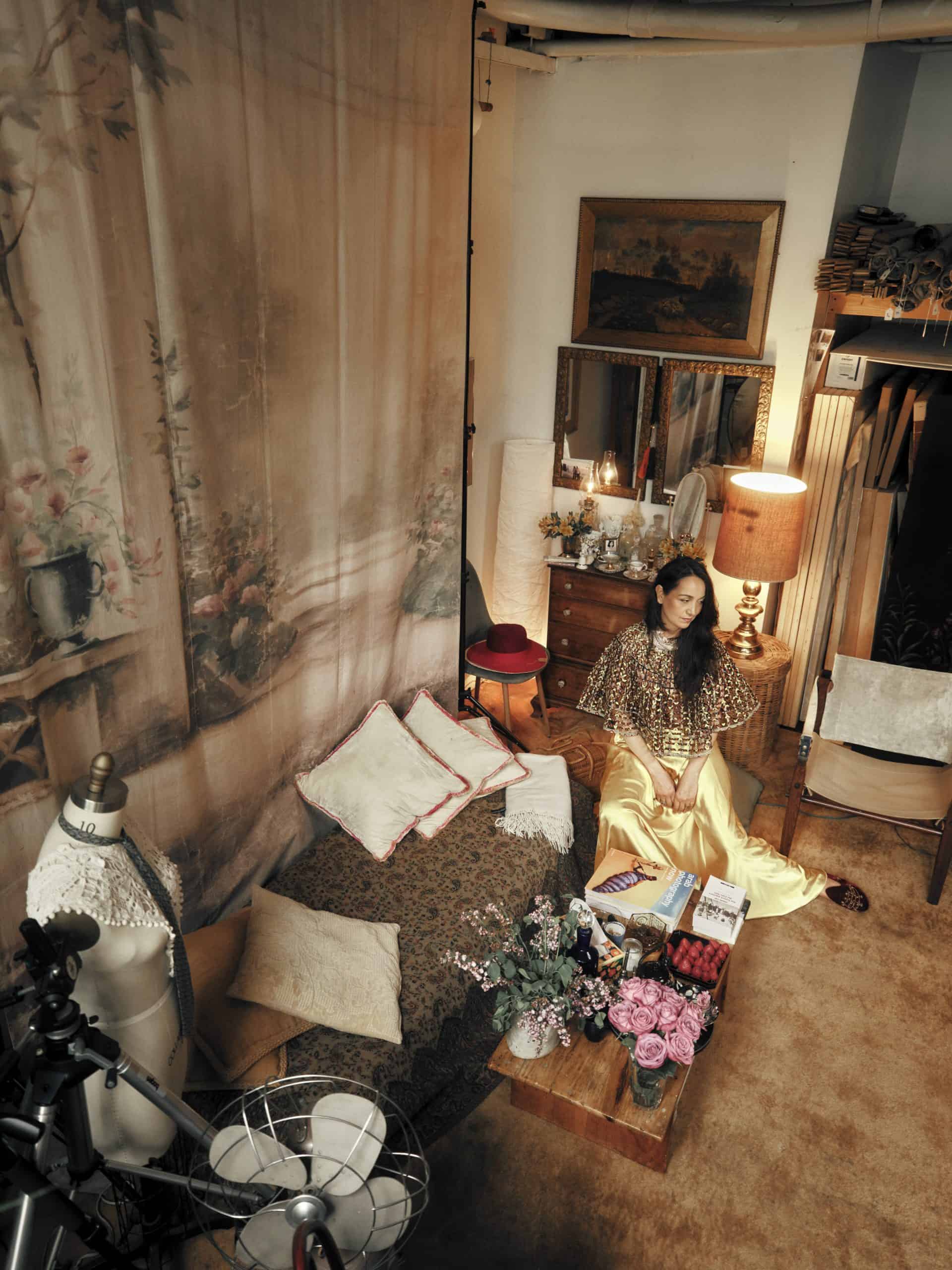

Faten recently opened her portrait studio in New York’s historic Westbeth building, a legendary artists’ residence in the heart of the West Village. Moreover, working with an early 1900s backdrop and printing using the traditional Kallitype process, she offers timeless, hand-crafted portraits that bridge past and present in a singular visual language.

IRK: You began your career in interior architecture. What inspired your shift into photography and multidisciplinary art?

Faten: I’ve always wanted to be a photographer. Since I was very young, it felt like an inner certainty something that never left me. But I first trained in interior architecture, a path that felt more stable and familiar, especially with several architects in my family. It was a more reassuring choice at the time. For a while, I tried to pursue both careers in parallel, and I created some beautiful things during that period.

But photography and eventually art as a whole gradually took over. It wasn’t about rejecting architecture, but rather responding to a deeper, more personal need. At some point, I couldn’t turn away from that voice anymore.

IRK: Was there a pivotal moment when you chose politically engaged art as your medium? How did memory and personal experience shape that choice?

Faten: I didn’t “choose” political art at a specific moment. Rather, I’ve always worked along those lines. My practice has always been rooted in political and social concerns, with a strong emphasis on the duty of memory. Whether in my early photographic explorations of abandoned spaces or in more recent projects like HALWA, I keep returning to the same question: what do we do with traces? And how does each regime erase the one that came before?

In Tunisia, this cycle of erasure is tangible. After the country’s independence in 1956, President Habib Bourguiba sidelined the legacy of the beys, the former Ottoman rulers of Tunisia. Later, Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali who took power in 1987 through a medical coup sought to erase the Bourguiba era in turn. Through these absences and abandoned sites, I question history, transmission, silence, and inherited wounds.

What matters to me is not nostalgia, but memory as a critical tool. My work lives in that tension between what is visible and what has been erased, between the personal and the collective a space where vulnerability becomes a form of strength.

IRK: Your work explores memory, trauma, and resilience. Why are these themes so central to your practice, and how does memory inform your creative process?

Faten: My work engages with memory, trauma, and resilience not as themes, but as states of being. I start from what has been forgotten, from ruins, from what remains after destruction. It’s a form of emotional archaeology. Consequently, each piece is an attempt at reconstruction. I photograph, I stitch, I mold, I perform gestures that try to piece the fragments back together.

In fact, my work has never taken the body neither my own nor others’ as a starting point. My focus remains memory, erasure, and reconstruction. I’ve rarely put myself in the frame. The only time my face appeared in a direct way was in Ring, a performative installation with punching balls, and later in the HALWA project. And paradoxically, that was the piece that was destroyed.

IRK: You often center women’s bodies and disrupt dominant narratives. How do you approach the responsibility of representing these stories through your art?

I don’t aim to represent ‘women’s bodies’ as a category, nor to speak on anyone’s behalf. However, I’m fully aware that female bodies, especially in politically or religiously repressive contexts, are often the first battlegrounds. What matters to me is creating spaces where what has been silenced, erased, or denied can reappear. It’s not a loud or didactic gesture; rather, it’s one of excavation and unveiling, always grounded in the personal.

IRK: Do you experience exile—personally, culturally, or symbolically? How does this inform your creative process and shape your sense of “home”?

Faten: Yes, I’ve experienced exile physically, but also symbolically and culturally. I left Tunisia. I lived in camper vans, with friends, on the margins. But I don’t see myself only as someone in exile. I exist in constant movement between languages, between geographies, between layers of memory. My art is born in those in between spaces, in that state of suspension. “Home” is not a place, it’s a condition, a pursuit.

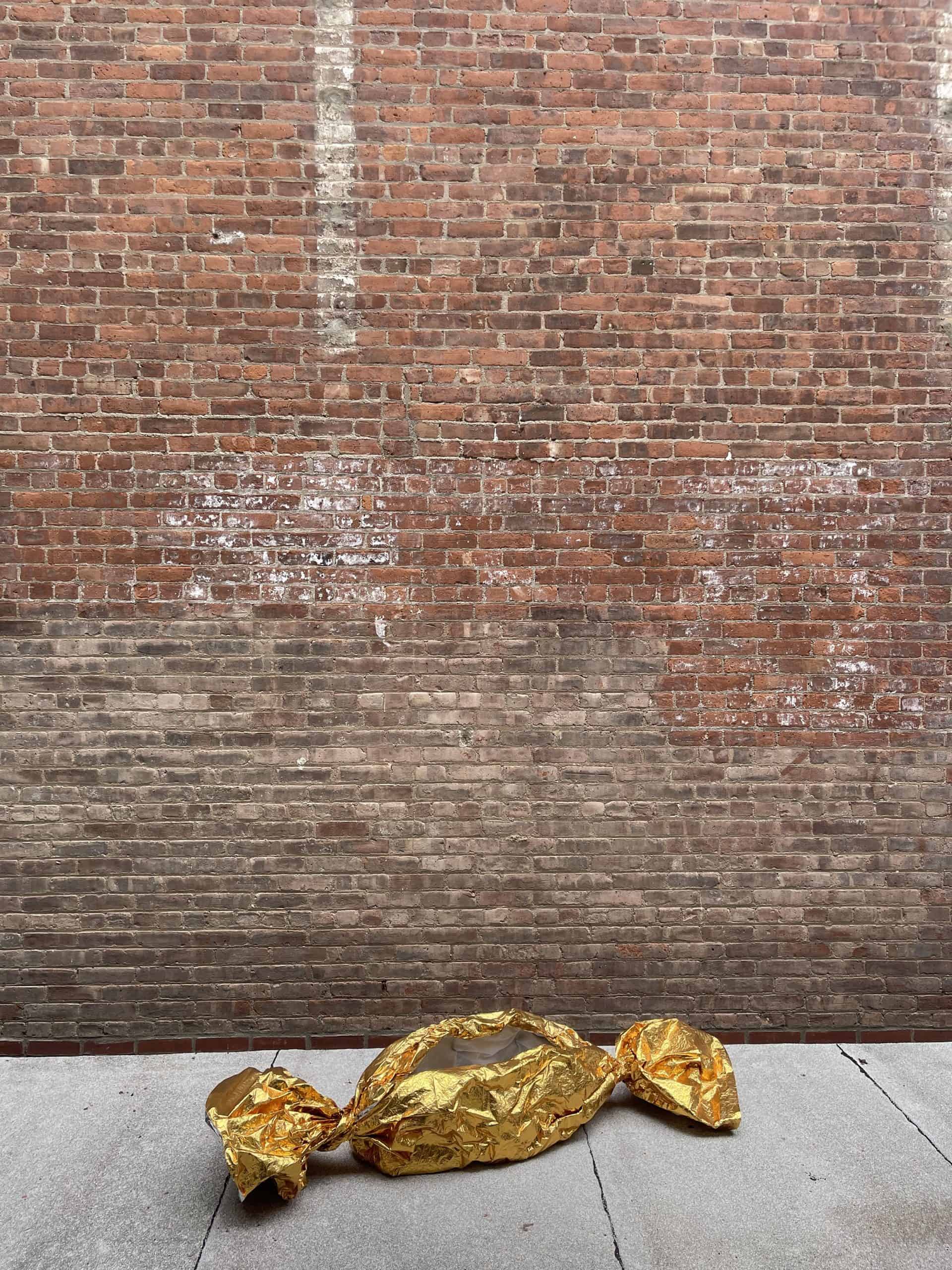

IRK: Can you share the story behind HALWA? What did the destruction of Punching-Ball teach you?

Faten: HALWA was born from a deeply impactful event: specifically, the destruction of one of my installations in Tunisia. The work was called Ring, a boxing ring with four punching balls suspended inside. Each punching ball bore my self-portrait, with my hair used as a veil. Through this, I denounced violence against women, regardless of their religious or cultural background. The audience was invited to strike the punching balls it was a live performance.

The piece had been purchased by the Tunisian state and exhibited in several institutions, including the Arab World Institute IMA in Paris.

But during a contemporary art biennial in Tunisia, it was violently dismantled, and three of the punching balls were publicly burned. Only one survived.

Two years later, when I left Tunisia, I carried with me an envelope containing charred fragments of the work. These burnt fabrics became the first witnesses of HALWA, a project I built as a slow, archaeological, and physical process of reconstruction. It took thirteen years of silence before it could emerge.

The title HALWA comes from a statement by a former Islamist minister who said, “Art must be sweet.” I took this phrase literally to reveal its absurdity. I wanted to challenge this demand for softness and complacency, as if art should never disturb.

IRK: What draws you to unconventional materials like wire, resin, and survival blankets?

Faten: In HALWA, I use ambiguous materials resin, wire, burnt fabrics but also survival blankets. Specifically, these blankets wrap the entire project. They are materials used to protect a burned body. Here, they symbolically protect a work born from an attempt at destruction. It is also a way to protect myself, creating a space of care in response to violence.

HALWA is a composite work, crossing sculpture, video, photography, and performance. It is a process of repair.

I’m currently preparing a solo exhibition of HALWA, which will open on July 2 at Westbeth Gallery in New York—followed by an Artist Talk on July 17. Ultimately, this show will mark a new chapter for the project, bringing it to life in a city that has been a space of both exile and rebirth for me.

IRK: How do you balance aesthetic beauty with the political urgency embedded in your work? Do you ever find one needs to take precedence over the other?

Faten: I don’t believe in a opposition between aesthetics and politics. Beauty is not a goal, but a tension. Sometimes, violence needs to be raw and exposed. Other times, it slips into softness. What matters most to me is to be truthful staying faithful to what I want to say, even if it disturbs.

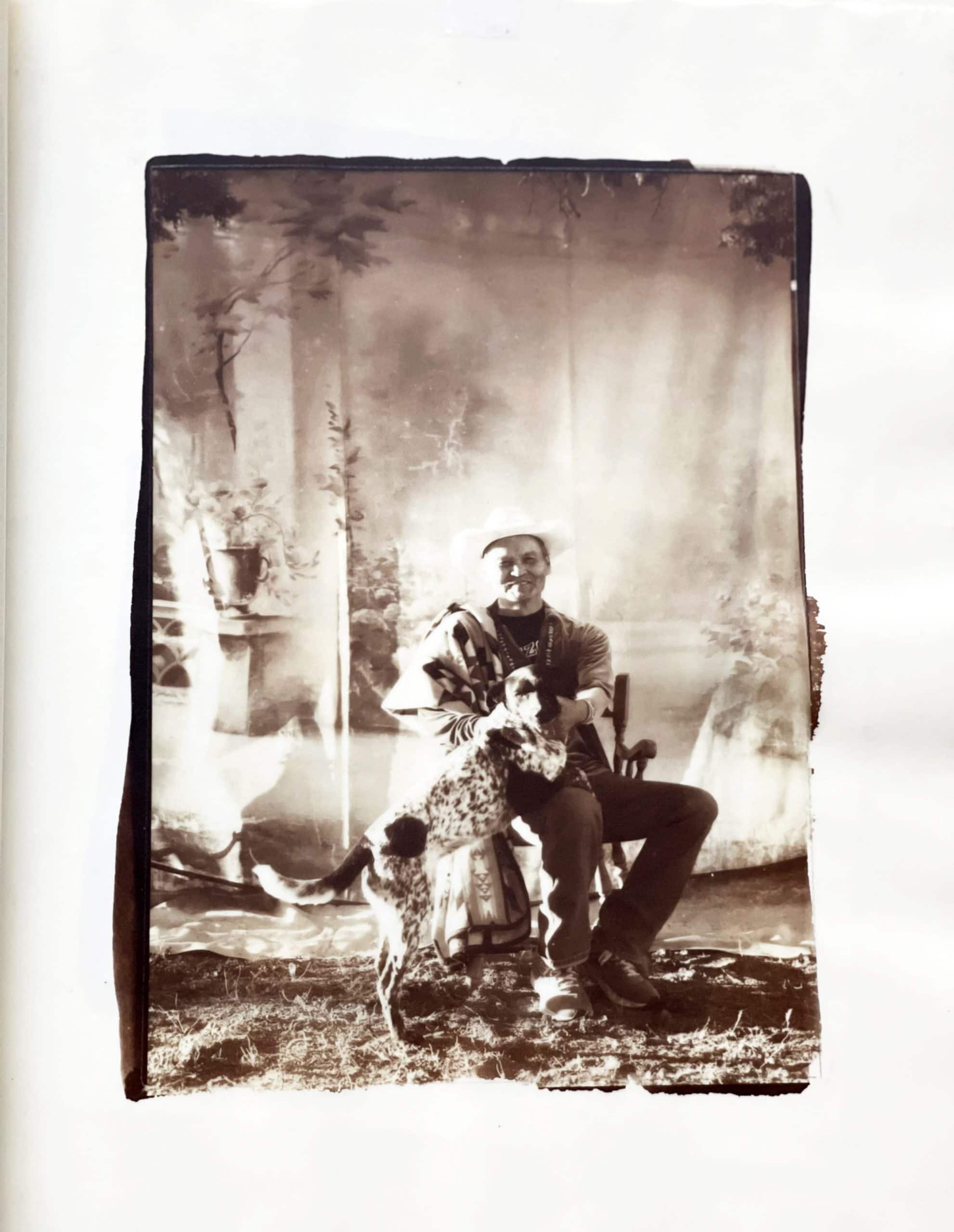

IRK: Itinerary, your project with Native American communities, is deeply collaborative. What has it taught you about heritage, healing, and solidarity across cultures?

Faten: Itinerary began in 2012, right after the destruction of Punching-Ball. While I was in hiding and keeping silent, I found an old canvas from 1900 at the back of a garage. I restored it and began taking it on the road across Tunisia. Each stop became an intimate exchange.

I would set up the canvas, listen to people’s stories, and take a portrait. That piece of fabric became both a bridge to others and a shield against trauma.

When I arrived in the U.S., it felt natural to continue this project with Native communities. They welcomed me like family. Living, even briefly, within their daily lives taught me that beyond the clichés of poverty lies an extraordinary force of transmission through songs, languages, crafts, educators, and activists.

The project showed me that collective wounds whether from colonization or censorship often resonate with one another. Healing, I’ve learned, often happens through shared experience and reciprocity. In photographing others, I’m also offering my own story. Itinerary has become a kind of living archaeology: each portrait weaves a thread of memory across cultures and reminds us of our shared ability to survive and, above all, to recognize ourselves in one another.

IRK: What are the challenges and responsibilities of working with communities whose histories differ from your own?

Faten: The main challenge is listening. Not projecting your own story onto someone else’s. Accepting that you won’t understand everything. Being fully present in exchange, in slowness, in vulnerability. And recognizing that sometimes, the greatest form of respect is knowing when to step back.

IRK: Your upcoming capsule collection transforms your photography into silk dresses. What inspired this fusion of fashion and image, and how do you see clothing as a vessel for storytelling?

Faten: My work in fashion is an extension of the same artistic approach. I created a series of sculptural dresses using my photographs. The fabric becomes archive, skin, flag. Each dress tells a story an embodied memory.

IRK: The Didon dress references mythology and resistance. What does that figure represent for you personally?

Faten: The Didon dress is inspired by the Carthaginian queen a figure of power, sacrifice, and resistance. For me, she represents women who say no, who leave, who build elsewhere. Additionally , it’s also a way for me to reconnect with my roots with a Mediterranean that is powerfully feminine and tragic.

IRK: You’re also creating performative culinary experiences. What role does food play in cultural memory and the transmission of identity?

Faten: Food is a universal language, a sensory archive, and a deeply intimate ritual. I never used to cook in Tunisia. My mother is an extraordinary cook, and her food was so exquisite that no one dared compete. It was only after leaving home that I began to cook, as a way of reconnecting with her, with myself, and with my cultural roots.

This is how Couscous by Didon was born, a project that fuses culinary heritage and artistic gesture. The name is a subtle nod to Queen Didon of Carthage, a figure of resilience and reinvention. Through this project, I share Tunisian food culture still underrepresented in the U.S. by curating immersive private dinners that blend flavor, storytelling, and scenography.

Recently, in collaboration with Eat Offbeat, I presented a performative dinner at Atelier Jolie (formerly Basquiat’s studio).

I offered a live demonstration of how to prepare brik, a beloved North African dish with Jewish-Tunisian roots, followed by a full Tunisian menu. It was an evening of sharing through taste, scent, and memory.

IRK: Tell us about your new portrait studio at Westbeth. What draws you to historic techniques like kallitype printing?

Faten: Recently, I opened a portrait and printing studio at Westbeth, New York, where I explore historic processes like kallitype printing. I’m fascinated by the relationship between photography and time. These slow, almost meditative techniques bring me back to the essence of looking of presence.

This studio represents a continuation of my Itinerary Project. While that work was nomadic, traveling through different regions and communities, here I develop the project rooted in one place Westbeth, a historically iconic artists’ residence. I am honored to join a community that has included remarkable artists such as Diane Arbus , Nam -June -Paik , Merce Cunningham, Gil Evans , Billy Harper, and many others…

Working with an antique studio canvas from 1900, which I restored and have traveled with for years. It serves as a backdrop in many portraits, paying tribute to a vanished era of studio photography. Moreover, in a world rapidly changing through technology and AI, returning to these older, slower methods is like a quiet form of time travel and resistance.

Those seeking something unique know where to come. Each portrait becomes a dialogue between past and present a slow, intentional act of memory.

IRK: Your visual language merges documentary photography with installation and sculpture. How do you decide which medium best serves each story?

Faten: Each project chooses its own medium. I don’t plan ahead whether a piece will become a photograph, an installation, or a performance. Instead, I let the subject lead. I respond to what it evokes and allow the work itself to guide the form it takes.

IRK: We support awareness of the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Which of these goals resonate most with your work and why?

Faten: Several of the goals resonate with my practice especially those related to gender equality, peace, justice, and cultural preservation. Art doesn’t save, but it can awaken, gather, provoke. And sometimes, that’s already a lot.

Website: www.fatengaddes.com

Instagram: @fatengeddes

Inspired by Faten Gaddes’ journey from architecture to activism? Dive deeper with IRK’s recap of their HUMAN Issue launch dinner at Splashlight Studios.

Share this post

Cannon is our Editor-At-Large since August 2016. He grew up in New York City and was influenced at an early age by rock and fashion. He is an award-winning celebrity stylist, fashion editor and creative director who has styled many of his favorite musicians including Annie Lennox, Cyndi Lauper, Jimmy Page and Shirley Manson. His wit, charisma, and style have made him a trusted and sought-after stylist by Hollywood legends such as Liza Minnelli, Willem Dafoe, Dennis Hopper, and Glenn Close.

Cannon has also worked with some of today's hottest celebrities, including Diane Kruger, Angelina Jolie, Matt Damon, Penn Badgley and Kellan Lutz. He was the first stylist to get Barbra Walters into a pair of jeans for a photo shoot, and had the opportunity to dress Michael Jackson as the KING OF POP for MTV. In addition, Cannon also founded PLUMA- a luxury costume jewelry collection made exclusively in Italy that was recently featured on the cover of Italian Vogue. As a result of working with great musicians and celebrities, Cannon has contributed to multiple publications including: Rolling Stone, Vogue, Time, Entertainment Weekly, Vanity Fair and W. He has styled large casts for every network including: Lost, Sopranos, The View, Project Runway, Kelly, The Today Show, Top Chef, and The Office. Cannon's expertise in fashion also has lent itself to him being in front of the camera as a style expert, with television appearances on E!, Style, VH1, CBS, NBC, ABC, TLC, and Bravo. Cannon has been an on-air spokesperson for TJ Maxx, Burlington Coat Factory, Chapstick, Pantene, Dove, and Peanuts/Snoopy Worldwide. He has also been profiled in American, German and Japanese publications. In addition, Cannon was instrumental in organizing an inaugural panel discussing fashion and film for MEIFF in which he also served as a participant alongside Jason Wu and Kathryn Neale Shaffer, contributing editor at American Vogue.

Whether it's obtaining real museum pieces for a Discovery Channel commercial or recreating 50 unique culturally observant costumes for the worldwide launch of the National Geographic Channel, Cannon's respect for authenticity and his gift of problem solving has left lasting impressions on everyone he has worked with. Additional commercial work also includes Saks Fifth Avenue, Target, Sony Music, RCA, Bravo Network, Sprint, Bergdorf Goodman, and Neiman Marcus.

Cannon has styled fashion shows for Jason Wu and the Life Ball in Vienna, Austria, starring THE BLONDS, which is the largest AIDS benefit runway show in the world, that year hosted by President Bill Clinton and Eva Longoria. Other fashion shows include Snoopy in Fashion, Joanna Mastrioni to name a few. He has also styled shows for Safilo and their licensed brands, which include Gucci, Christian Dior, Emporio Armani, Ralph Lauren, Dior Homme, Max Mara, Marc Jacobs, Marc by Marc Jacobs, Stella McCartney, Banana Republic, Tommy Hilfiger.

Read Next