HIROSHIMA, Hiroshima, hírou-ʃímə

Agnese La Spisa

The Hiroshima Student Photography Movement Revisited at Paris Photo 2025

At Paris Photo 2025, beneath the glass vaults of the Grand Palais, one of the most unexpected and quietly powerful presentations stood apart from the spectacle of contemporary works and international galleries. Tucked between striking visual experiments and glossy large-format prints, visitors encountered something far more modest in appearance but monumental in meaning. It was the student-led photography project HIROSHIMA, Hiroshima, hírou-ʃímə, created between 1968 and 1971 by members of the All-Japan Students’ Photo Association (AJSPA).

The exhibition offered a rare chance to see this project outside Japan. The venue couldn’t have been more fitting. In a place dedicated to the world’s photographic voices, these students, many barely in their twenties at the time, quietly reclaimed a space in the conversation about memory, responsibility, and the purpose of documentary photography.

How a Student Photography Revolution Began

Before the AJSPA existed, Japan had already witnessed a boom in photography clubs as cameras became more accessible in the early 20th century. By the 1930s, student-based photography groups were active across many campuses. These grassroots clubs formed the groundwork for what would officially become the All Japan Students Photo Association in 1952.

Supported logistically by Fuji Film, the AJSPA grew at lightning speed. By 1953 it boasted nearly 35,000 student photographers across more than 1,100 schools. The organization served as a national network where students could learn from leading photographers like Domon Ken and Kimura Ihee. Moreover, it allowed them to share their work and build collective platforms for exhibitions and publications.

A Collective Way of Seeing

By the late 1950s, the AJSPA had embraced what they called “collective production.” Instead of focusing on individual expression (still the norm for amateur photography) students turned their cameras toward shared themes, usually pressing social issues. They divided responsibilities, shooting different sites or communities. They would then merge the results into a unified visual narrative.

This method erased hierarchy. A viewer could not tell who shot which photograph. Instead, the images spoke with a single collective voice. It created the kind of conviviality and constant exchange that emerge only when creativity is rooted in shared purpose.

Under this framework, the group tackled subjects far ahead of their time: pollution, industrialization, and the human cost of Japan’s economic miracle. Some of these efforts eventually became photobooks, including HIROSHIMA, Hiroshima, hírou-ʃímə. Others were completed years later by alumni, long after the height of the movement had passed.

By the mid-1960s, however, collective production had begun to lose steam. It risked becoming routine, a way to maintain club activity more than to innovate. That is when a new figure entered the story and shifted its direction entirely.

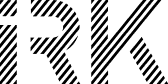

Hiroshima- Three Girls (Fukushima-chō), 1968, Vintage gelatin silver print, 20.8×31cm, Courtesy of MEM, Tokyo

Turning the Lens Toward Hiroshima

Photography critic Tatsuo Fukushima, who became the association’s de facto leader during this period, urged the students to rethink where the “real crisis” lay. While Japan was roiled by student protests and political upheaval, Fukushima challenged them to look elsewhere.

Between 1968 and 1971, students traveled repeatedly to Hiroshima every summer. They turned their cameras toward the people, neighborhoods, and rituals that defined the city in its state of rapid reconstruction. They later coined the term hírou-ʃímə, written phonetically, to distinguish the place they encountered from the simplified symbol that “Hiroshima” had become in public discourse. The word suggests something that must be felt, learned, and processed. It is an experience rather than a label.

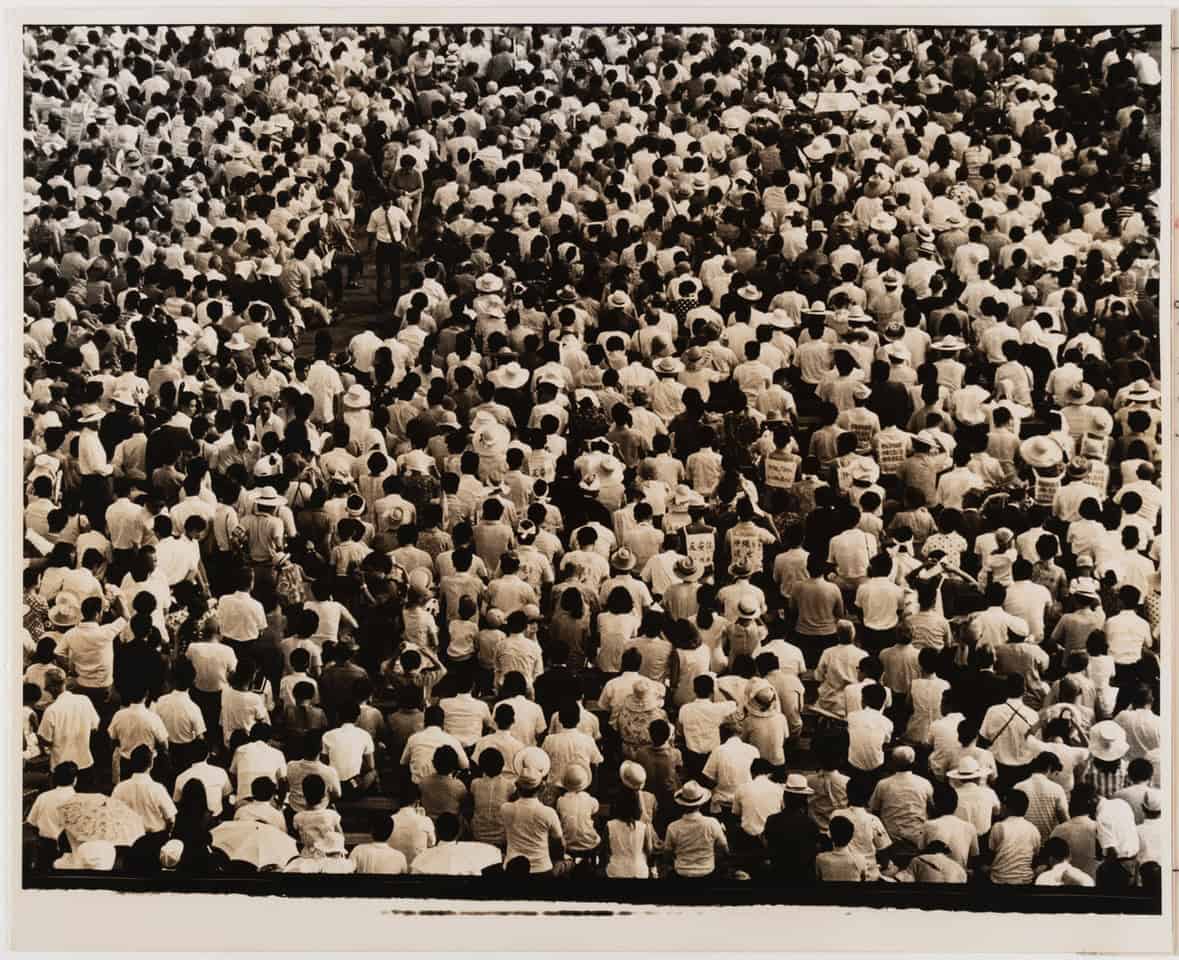

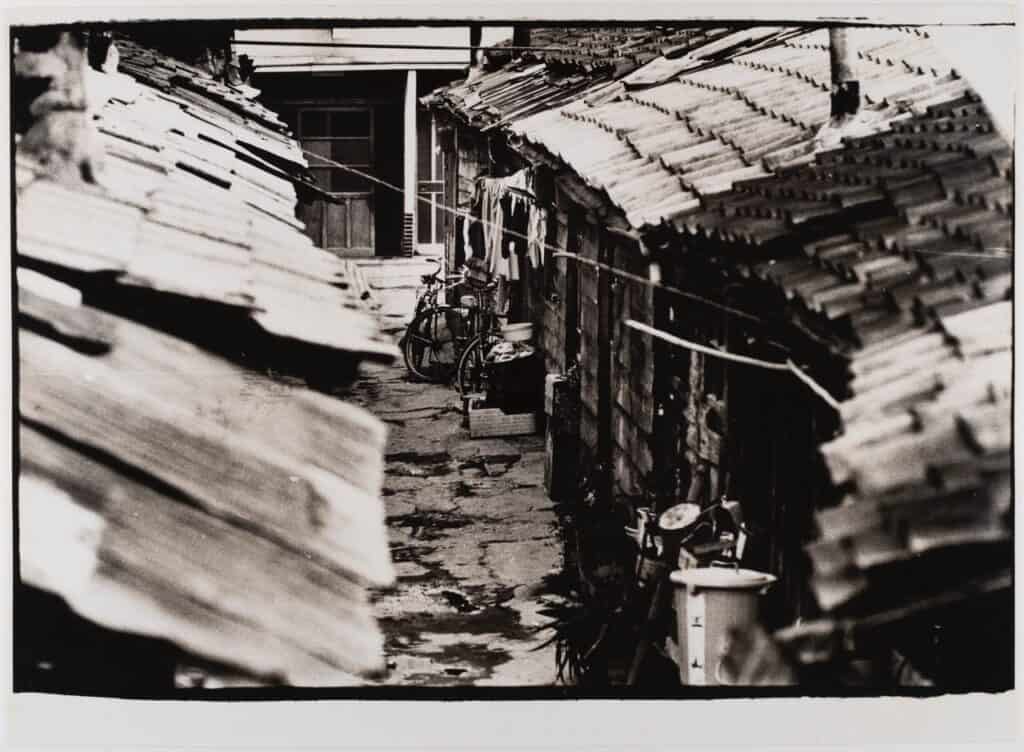

Paris Photo visitors saw this nuance unfold not through a grand narrative, but through a mosaic of scenes. They witnessed the changing architecture of the city and the daily rhythms of its residents. Furthermore, they saw the solemnity of the August 6 Peace Memorial Ceremony. Additionally, they saw the soft glow of floating lanterns on the river and the quiet tension of neighborhoods once known as atomic bomb slums.

Unexpectedly, photographs of student protests at Hiroshima University, captured during the same period, also slipped into the story. These images showed how the anxieties of the era intertwined.

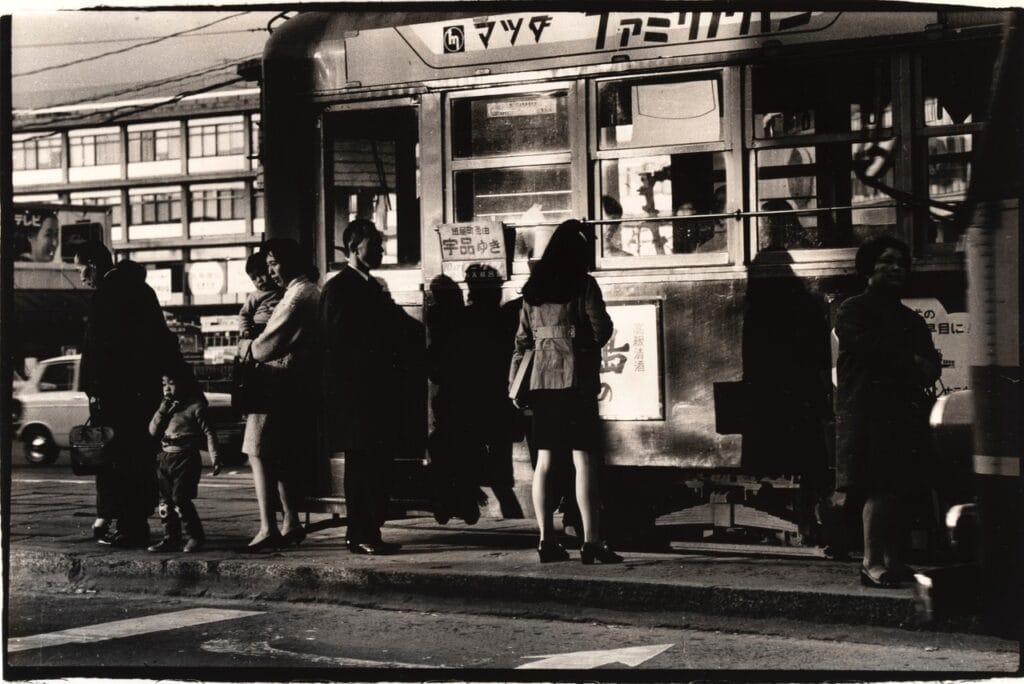

Hiroshima- Streetcar and Girl (Kamiya-chō), 1969, Vintage gelatin silver print, 19.5×30.1cm, Courtesy of MEM, Tokyo

A Project Rooted in Reflection, Doubt, and Human Contact

Hiroshima Day, as the students themselves called the project, was never just about photography. After each session, they wrote long reports by hand or mimeographed collective statements. These documents examined not only what they had photographed but also what it meant to do so. Their notes, excerpts of which were on display at the Grand Palais, revealed the emotional difficulties of approaching hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors). Some residents greeted the students with silence, others with suspicion, and others with unexpected warmth. Indeed, the project became as much about ethical confrontation as about image-making.

The original photobook, published in 1972 as HIROSHIMA, Hiroshima, hírou-ʃímə, is considered a cult object among Japanese photography enthusiasts, yet it cannot contain the full scope of the project. Paris Photo 2025 expanded that universe by presenting original prints, early exhibition materials, and archival documentation together—for the first time in Europe. This created a fuller understanding of what Hiroshima Day represented.

Why This Project Matters Now

As we approach the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II, the question the students asked, What does Hiroshima mean today?, feels newly relevant. Their work suggests that Hiroshima is not a historical endpoint. Instead, it remains an ongoing responsibility. It asks us to look, to listen, and to rethink the narratives we inherit.

At Paris Photo, visitors lingered longer in this booth than in many others. Perhaps because the images didn’t shout; they whispered. Perhaps because they weren’t polished statements but thoughtful observations. Or perhaps because they came from a generation of young people that, much like today’s youth, were wrestling with questions bigger than themselves.

Share this post

Agnese La Spisa is an Italian creative based in Italy, specializing in publishing and fashion communication. At IRK Magazine, she brings together creativity, research, and design to shape stories with clarity and style. Curious and collaborative, she is driven by a passion for exploring culture, aesthetics, and the narratives that connect people, ideas, and disciplines.

Read Next