Jill Viney: Crafting Artistic Legacy

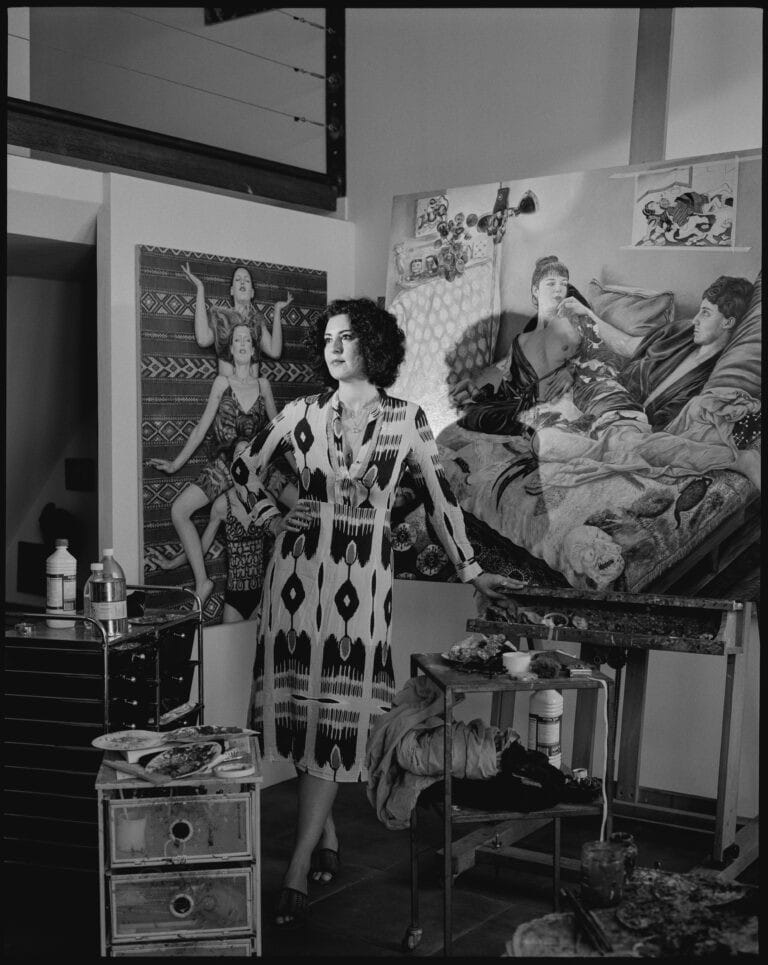

IRK Magazine

Jill Viney, a multimedia artist, has spent nearly four decades shaping the distinctive narrative in her work. Within her Manhattan studio, Viney’s large-scale color theory paintings share the space with wall-mounted polymorphic sculptures emanating internal illumination. Beyond conventional mediums, her “environments” encapsulate the perpetual conflict between domesticity and the artist’s calling. Navigating through life-size sculptures reminiscent of alien lifeforms, Viney’s journey is a testament to an enduring commitment to artistic exploration and innovation.

The ongoing series from Pen + Brush means to acknowledge Contemporary Art’s ever-changing landscape. This third iteration; “NOW: As a Consequence of Fact” builds on the evolving nature of “the now” as it pertains to today and reminds viewers of the impossibility of a finite definition of contemporary art by showcasing art that spans across time. Jill is currently working on a new body of work which will be exhibited in New York City shortly.

In this interview, Jill Viney unveils the profound journey of her life and art.

Can you share more about your artistic journey, especially how your experiences at Sarah Lawrence College and Columbia University influenced your work?

“My college and graduate school experiences were a break from the previous eighteen. A wider

world opened. I met people of different backgrounds, and wider education with broader ideas. My teachers opened worlds–art history, contemporary art, and the philosophy that accompanied them.”

You have mentioned Joseph Campbell and William Stanley Rubin as influential figures. How did their teachings impact your artistic philosophy and approach?

“Joseph Campbell and William Rubin were the most powerful. I had been posted with my family

in the United States–Georgia and Alabama, and abroad in Germany and France–but with a typical American high school education. College always opens doors of thought. These two men opened philosophy, visual arts, and the understanding of them to me. However, looking back, these were areas that I was innately drawn to. It was a bit like coming home to myself.”

What was it like to transition from color field and abstract expressionism in the ’70s to working with plastic and fiberglass in the ’90s? Can you elaborate on how your artistic style evolved during these periods?

“My home was filled with color and design, my mother had been an interior decorator. I think I loved color innately. Images of color in abstract, color field paintings, and hearing Rubin lecture on them was exhilarating. In graduate school, I began with abstraction as did many of my fellow students. Ten years after graduation in painting, my imagination had begun to run

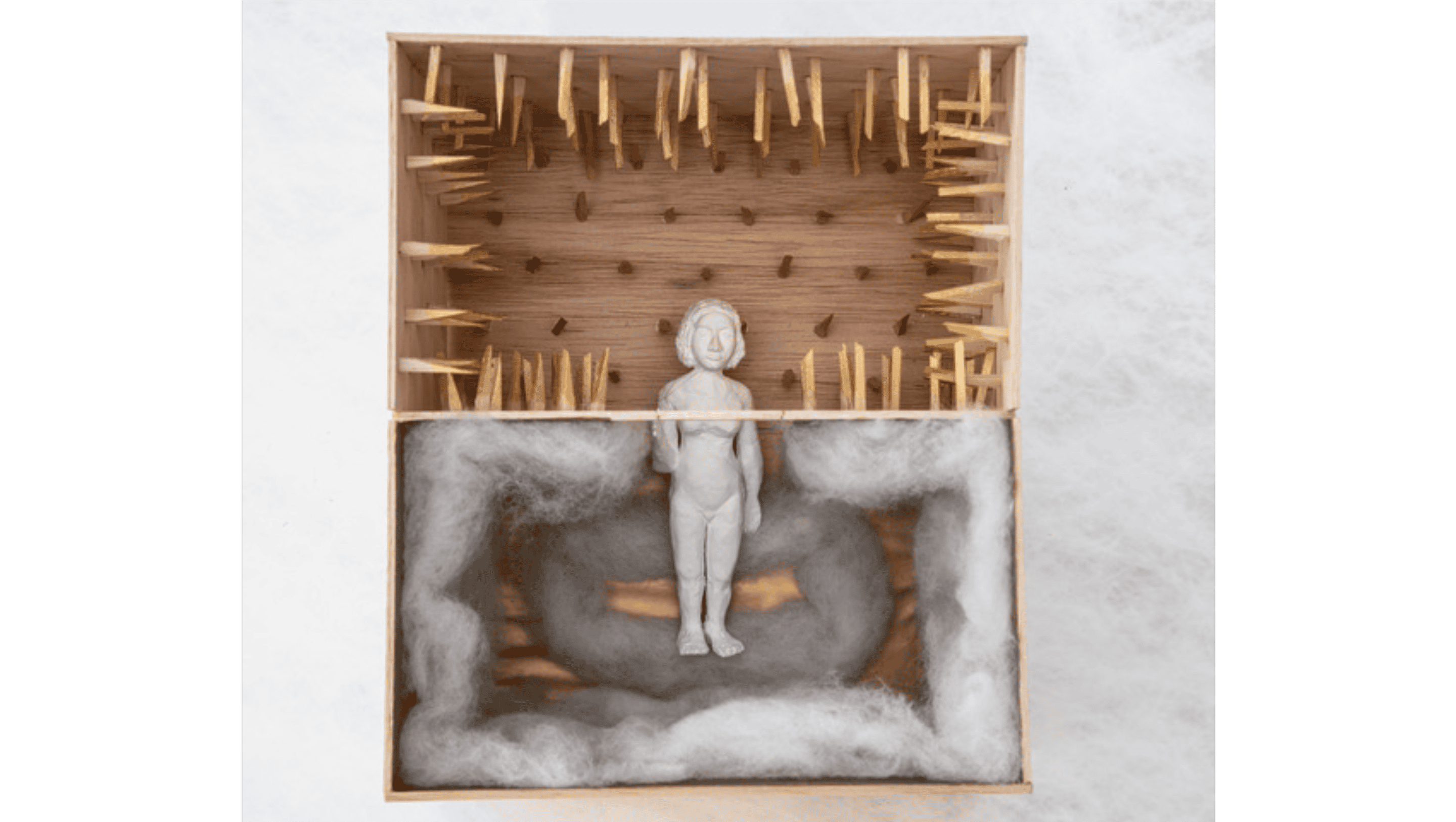

dry. One starts with impulses to do, get started, and make. The more one works and sees the results, one takes stock. Painting began to seem flat and two things happened: I wanted to construct forms and my ideas revolved around experiences in my life; I had two children. A strong force in my homemaking and my studio had to balance each other. I needed to make ideas that reflected that. The environments followed. Afterwards, my drive to construct resulted in three-dimensional bas-relief forms that hung on the painting and offered more space in the painting. In 1890 I made my first transparent wall sculpture with molded plexiglass.

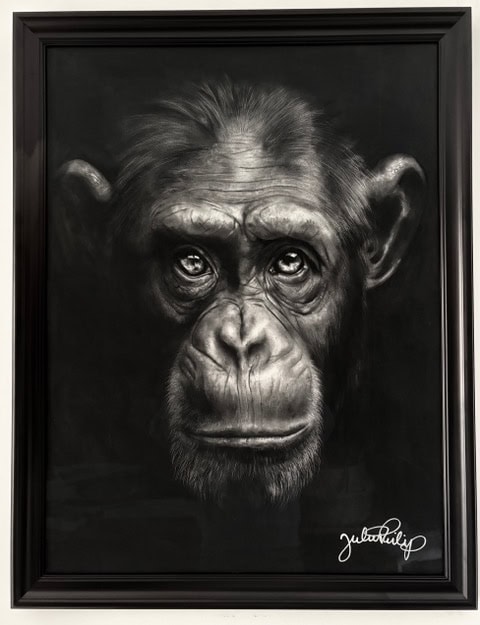

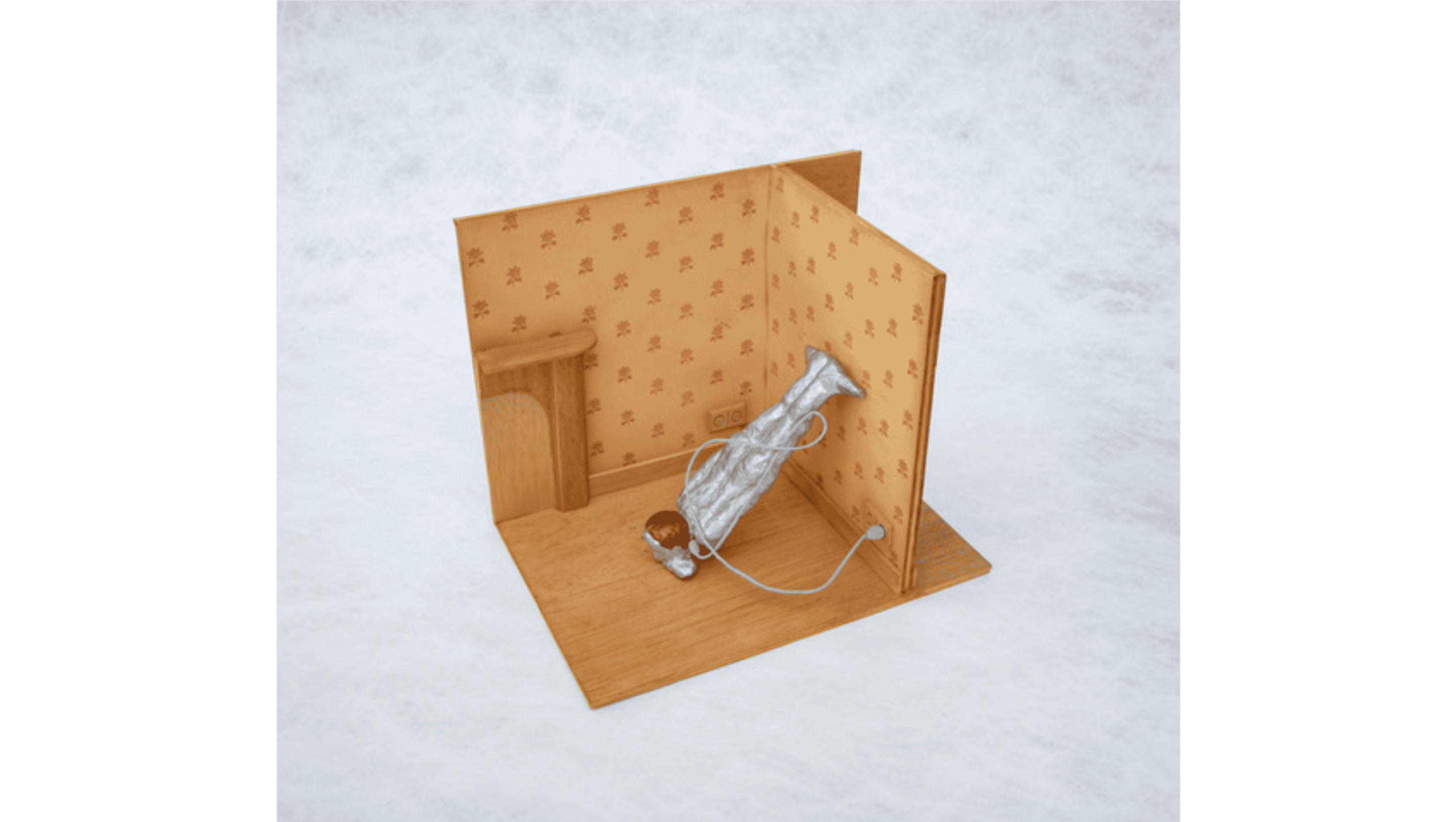

Jill Viney, “Dream”, 1980 Jill Viney, “Woman Vacuum”, 1979

What prompted your shift from painting to three-dimensional wall sculptures, and large sculptures inspired by deep-sea creatures?

“At that time, I had also discovered scuba diving. On a trip to the Caribbean, Through transparent glass goggles, a whole new world appeared. Fish, sea anemones, squid, and octopus moved through the water that I could touch. The light and colors were vibrant. Those two experiences came together.”

You have previously spoken to the challenges faced by women artists, particularly in the ’80s and ’90s. How did these challenges influence your career decisions and the themes explored in your art?

“I have mentioned the impact of having children and maintaining a studio life. In the seventies AIR (the women’s co-op) had formed and the New Museum had been created by Marcia Tucker. They answered the need for a more inclusive system to show art that did not fill the narrow confines of uptown museums. Men were the gatekeepers: they were the gallerists, the critics, the curators by and large. In business men have always been directed to succeed; it is possible that men trust men more and women less. The Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C. was founded in the ’80s. It contains powerful art by women.”

Can you elaborate on the connection between your California roots, the sea, and the anthropomorphic forms in your sculptures?

“I was born in California in a small seaside town, Carmel, which is very beautiful. I used to play by the tide pools and swim in the ocean. Its topography is very powerful for me. Many marine forms fascinate me and their workings as well. What comes to me in my work are sensations and images from my experiences.”

Jill Viney, “Orbital”, 2007, Fiberglass

How does Joseph Campbell’s philosophy that “you are what you see,” resonate with your own views on art and life?

“Joseph Campbell quoted a Buddhist-Tibetan saying, “You are what you see.” He meant what we see, perceive, and understand what lies before us. There are people who do not believe and understand what they see. We all come with preconceptions; what others have understood and told us. Therefore, what we see before us has been colored by others’ views. If we can suspend those other views, we will see differently and for our truer self.”

Are there specific changes or developments in the art world that you find particularly encouraging or challenging?

“For me, the art world now is a cross between a circus and a museum. Around the globe, there are artists working and showing. There are several tiers of galleries, art fairs, and auctions. More people are writing, talking, and thinking about art than ever before. A lot of strong work is being made and discovered. This is the circus; it gives more opportunities for art discovery. Next, the museum identifies and salutes quality and talent. At every age, there is the stage, the players, the forgotten, and the rediscovered. Now we are all of that.”

Which sustainable goal do you associate with and why?

I would choose sustainable cities and communities because, without these, humans have no hope. The topic also links to water, land, rising seas, and glacier melt issues which connect to climate change. Unless humans have land to stand on, grow food on, and live lives on we will have nothing. Many other issues become secondary: supply-food exchanges, livable wages, education, life expectancy, weapons proliferation, and peace in space or on Earth. It all comes down to what we humans can affect in our lifetimes. We must start with our communities, links between communities, links to states and countries and continents – our world, our Earth.

Jill Viney, “Pulse II”, 1995, Fiberglass

Jill Viney’s artistic journey, as revealed in this interview, is a testament to resilience, evolution, and a relentless pursuit of artistic truth in a world that continually unfolds on the stage of creativity.

Share this post