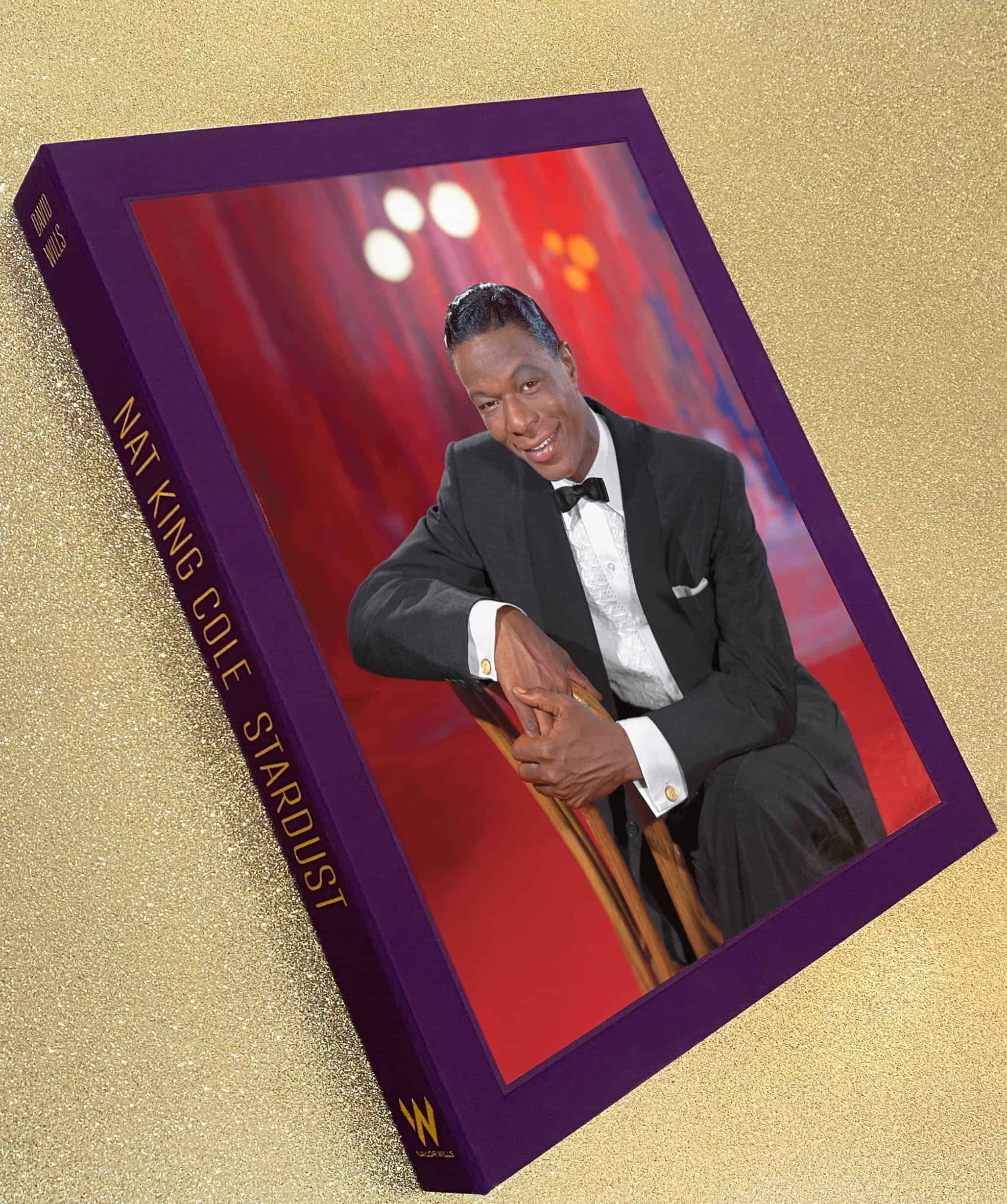

Nat King Cole // Stardust

Brendan Cannon

This June will mark the release of a very special, limited edition publication. On the legendary singer, jazz musician, style icon, and civil rights activist Nat King Cole.

Author David Wills whose books have included various legendary subjects such as Marilyn Monroe, Frank Sinatra, Audrey Hepburn, Ara Gallant, and supermodel Veruschka to name a few. Collaborated with Nat King Coles daughters, and Johnny Mathis, along with contributions from Quincy Jones and Leslie Uggams.

This glossy 272-page book housed in a luxury clamshell case with a soft cashmere lining is the first publication from Nailor Wills publishing. We spoke to David about the life and work of Nat King Cole:

1. Please tell us how you came to write a book on Nat King Cole, were you a big fan of his? I see that his family is involved, did they want a book on their father to keep the legacy alive?

The book was essentially a labor of love to commemorate Nat King Cole’s 100th birthday. I was originally approached about doing the book by the representative for Cole’s family. I was so honored. At the time I was surprised to learn that the definitive photographic retrospective had never been published. Cole’s twin daughters, Casey and Timolin, were only three years old when their father passed away. Therefore, they have come to know him through family photos and stories told to them by their late mother, Maria.

What they brought to my attention was the generosity and humility of their father, and the radiating effect those qualities had—still have—on anyone whose lives he ever touched. Cole is one of the great contributors to “the soundtrack of our lives.” Casey and Timolin have done an extraordinary job carrying on their father’s legacy. With their non-profit foundation Nat King Cole Generation Hope, which provides access to music education for children with the greatest need. This book was essentially their idea. Made possible through their love for their father and dedication to preserving his legacy.

2. What was Nat’s first big hit, since it was played on radio did most people know he was African American? And being so, did he run into a lot of prejudice during those times in the music industry?

By the very nature of his sound and style—jazz bebop—Cole’s ethnicity seemed to be evident. Also, with his band The Swingsters, he recorded for Decca’s “race records” label, Sepia. They first topped the R&B chart in 1942. They signed with the new company Capitol Records that year and as The King Cole Trio scored with “Straighten Up and Fly Right” in 1943, followed up with “(I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons” and “(Get Your Kicks On) Route 66.”

Encouraged by wife Maria, Cole evolved into a popular music vocalist. Soon recording love songs—a notable first for a black male singer. An example would be “Mona Lisa,” arranged and conducted by Nelson Riddle in 1950. Which was a B-side that turned into a huge hit. Five weeks at #1 on the Billboard singles chart—and won the Oscar for Best Song. This was after “The Christmas Song” and “Nature Boy.”

The King Cole Trio played mostly black clubs in Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York City. Staying in separate but not equal accommodations. However, after one hotel refused Nat and Maria their reserved rooms, he sued and was awarded reparations and damages.

The crucial incident played out in Birmingham, Alabama on April 10, 1956, in front of a white audience, which was infiltrated by members of the KKK, seeking to harm, even kidnap, Cole. Mid-performance—Nat at the piano—several of these men rushed the stage, grabbing him, and injuring his head and back. Musicians were assaulted as well as Cole was hustled backstage, and the attackers escaped. Nat returned to address the audience, saying he would not continue the show, and how shocked he was since he simply wanted to entertain. The next night’s performance, for a black audience, was canceled, and Nat vowed to never return to The South.

Cole made incremental moves to confront discrimination in Las Vegas. Initially forced to room in the “negro neighborhood,” he later parked a trailer in the back parking lot of the hotel while playing its showroom. His white manager stayed in the hotel. Nat then used his leverage as a Vegas draw to secure rooms, though segregated, for him and his band, as long as they did not enter the casino, dine at the restaurants or use the pool. Starring at the Sands Hotel, he was able to insist on full accommodations and access.

There was also the controversy over his buying a house and moving into a “residential covenant” neighborhood (an agreement between white homeowners to sell their properties only to Caucasians): a public battle Nat and Maria won in 1948.

3. Did Nat ever travel to Europe or South America to perform on tour or was he just touring the United States? Did he have any impact on other countries at the time, was his songs being played on the radios of Europe, or was he limited to the USA?

Cole became a premiere attraction across the country—singing at the most posh venues—and an international star, touring the UK and Europe, meeting royals, traveling to Japan, Central and South America, Cuba, and Australia, where he was received with Sinatra or Elvis-like fandom.

4. In your book there is a quote from Billy Eckstine “They weren’t ready for black singers to sing love songs. It sounds ridiculous, but it is true. We weren’t supposed to sing about love.” How was Nat able to sing so many romantic love songs during this time successfully?

Cole’s success changed perceptions and opportunities as his intimate vocal style and accessible manner jump-started an inevitable crossover, leading to never-before heights attained by a black male singer. There was even a friendly rivalry between Cole and Frank Sinatra. The smooth, gentlemanly Nat, and love songs, were a perfect match.

5. Did Nat compose and write his own songs? Was he into different types of music, different genres?

For Decca’s Sepia label, the group recorded Nat’s own compositions “Gone With the Draft” and “That Ain’t Right,” highlighting his exceptional jazz piano skills in bebop mode. For Capitol Records, as The King Cole Trio, they hit the charts with another Cole tune, “Straighten Up and Fly Right.” Nat had received classical piano training in high school, while at the same time being a fan of jazz piano great Earl Hines.

6. We all know the song “Unforgettable”; what do you feel is his most important song? Did Nat write and sing songs about racism the way Billie Holiday did with “Strange Fruit”?

The yearly holiday return of “The Christmas Song” comes to mind; Nat’s recording has become the definitive version, the favorite by far, never to be surpassed.

Very soon after the attack in Birmingham in 1956, Cole, in a plea for brotherhood, recorded “We Are Americans, Too”; a big departure for him, but too much of one for Capitol Records, which never released the track. However, decades later in 2009, the anthem was a highlight of Let Freedom Ring: The Music of the Civil Rights Movement, a compilation produced by Time-Life, with spoken word by President Barack Obama, from his inauguration speech. A sample lyric: “All our future is here / Everything we hold dear.”

7. Nat had his own TV show on NBC, was he the first African American to do so? How do you think this influenced other African Americans watching one of their own on TV? What was his show like?

Though not exactly on the front lines of the civil rights movement, Cole brought black and white people together through his music. For millions of white Americans, The Nat King Cole Show was their first experience of a black host, singing and interacting with black and white guest performers, often his friends. He initiated a breaking down of ugly stereotypes forced on black Americans through decades of injustice.

He was sophisticated, elegant, charming—he was extraordinarily gifted, with a knack for singing to and for all audiences. It was a uniting experience. Some may have criticized him at the time for being a white person’s idealized version of what a black person should be. But I don’t agree. He was just himself—a beautiful and refined human being. One of the most profound statements Nat King Cole ever made was: “The important thing is for negroes and whites to communicate. Even if they sit on separate sides of the room, maybe at intermission a white fellow will ask a negro for a match or something, and maybe he will ask the other how he likes the show. That way, you have started them to communicating, and that’s the answer to the whole problem.”

8. Tell us a bit about Nat’s movie career, how did he get the attention of Hollywood producers, and do you feel his movie career helped him sell records? Did his popularity in movies lead him to the TV show or did the TV show lead him into movies?

In the ’40s and early ’50s, Cole starred in quite a few musical featurettes. As his fame grew, studios capitalized on his star power in small roles, essentially played himself—for example as a club pianist/singer, establishing the mood, in the LA noir The Blue Gardenia (1953), but the 1956-57 television show was far more important to him than movie projects. Cole’s career as an actor climaxed in 1957 with Sam Fuller’s China Gate, in which he convincingly played Goldie, a soldier of fortune, near the end of the French-Indochina War.

His only lead role, as composer W.C. Handy in St. Louis Blues, costarred Eartha Kitt, Cab Calloway, and Ella Fitzgerald, but made little impression on critics and audiences in 1958, and no studio contract was forthcoming. Nat played a singer in the suspense drama Istanbul (1957), and a club owner in the social/racial melodrama Night of the Quarter Moon (1959), which was never released in The South. His last movie role placed him in the Wild West with Jane Fonda and Lee Marvin for Cat Ballou, released after his death in 1965. As Sunrise Kid, a Greek-chorus-type troubadour, he “narrated” the film, singing verses of “The Ballad of Cat Ballou.” In addition, several times Cole was called upon to lend his authority, tone, and bankability to the recording of movie theme songs—my personal favorite being the Joan Crawford melodrama Autumn Leaves (1955).

9. Nat had a very strong look, how would you describe his fashion style on stage and off?

By the height of his fame, Mr. Cole would earn a reputation as one of the most sharply-dressed men in the business. In fact, the term “natty dresser” was apparently coined in reference to Nat. His personal style in particular—sleek polo shirts paired with super-slim trousers and dark suede shoes; luxe cardigan sweaters in neutral shades; precise blazers in blue, black, or gray—has had considerable influence. He’s now a sartorial role model: dapper, debonair, snappy in sportswear, elegant in black-tie. Always sharply tailored—usually by “tailor to the stars” Sy Devore—even in the studio, his tweed porkpie hat and black horn-rim shades are now considered the essence of ’60s cool.

10. What is different about this book, and what do you want fans of Nat King Cole to walk away with from this book that is different from other books about him?

To begin, we hear from Timolin and Casey in their heartfelt foreword to the book. It’s coupled with a very personal introduction, written by Johnny Mathis. As the book is extremely large in format—14×17.75 inches. It was very important that the images be of the most exceptional quality. For this reason, we went back to the original negatives, transparencies, and photographs. In some cases, images had to be scanned. Laboriously cleaned and color corrected to restore them to their original vibrancy.

Capitol Records was wonderful in their understanding of our need for first-generation source material. The book contains many never-before-seen or published images from their archive. Complemented by quotes from Cole’s contemporaries and his recent and current admirers. Also, Nat King Cole: Stardust includes rare personal letters and telegrams from President John F. Kennedy, President Dwight D. Eisenhower, President Lyndon B. Johnson, Jackie Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr.

I think his daughter Timolin said it best: “Our father was a pioneer who transcended color and race.” There’s something about Cole’s voice that reaches into your heart and just stays there—it’s a warmth, a comfort. Being able to extract emotion through your art is an extraordinarily powerful gift. Music is healing, and Nat King Cole was—still is—one of the greatest healers of our time. Ultimately, at the core of his legacy was Mr. Cole’s hope to unite, to convey joy, to give pleasure—as he said, “to make people happy.”

Share this post

Cannon is our Editor-At-Large since August 2016. He grew up in New York City and was influenced at an early age by rock and fashion. He is an award-winning celebrity stylist, fashion editor and creative director who has styled many of his favorite musicians including Annie Lennox, Cyndi Lauper, Jimmy Page and Shirley Manson. His wit, charisma, and style have made him a trusted and sought-after stylist by Hollywood legends such as Liza Minnelli, Willem Dafoe, Dennis Hopper, and Glenn Close.

Cannon has also worked with some of today's hottest celebrities, including Diane Kruger, Angelina Jolie, Matt Damon, Penn Badgley and Kellan Lutz. He was the first stylist to get Barbra Walters into a pair of jeans for a photo shoot, and had the opportunity to dress Michael Jackson as the KING OF POP for MTV. In addition, Cannon also founded PLUMA- a luxury costume jewelry collection made exclusively in Italy that was recently featured on the cover of Italian Vogue. As a result of working with great musicians and celebrities, Cannon has contributed to multiple publications including: Rolling Stone, Vogue, Time, Entertainment Weekly, Vanity Fair and W. He has styled large casts for every network including: Lost, Sopranos, The View, Project Runway, Kelly, The Today Show, Top Chef, and The Office. Cannon's expertise in fashion also has lent itself to him being in front of the camera as a style expert, with television appearances on E!, Style, VH1, CBS, NBC, ABC, TLC, and Bravo. Cannon has been an on-air spokesperson for TJ Maxx, Burlington Coat Factory, Chapstick, Pantene, Dove, and Peanuts/Snoopy Worldwide. He has also been profiled in American, German and Japanese publications. In addition, Cannon was instrumental in organizing an inaugural panel discussing fashion and film for MEIFF in which he also served as a participant alongside Jason Wu and Kathryn Neale Shaffer, contributing editor at American Vogue.

Whether it's obtaining real museum pieces for a Discovery Channel commercial or recreating 50 unique culturally observant costumes for the worldwide launch of the National Geographic Channel, Cannon's respect for authenticity and his gift of problem solving has left lasting impressions on everyone he has worked with. Additional commercial work also includes Saks Fifth Avenue, Target, Sony Music, RCA, Bravo Network, Sprint, Bergdorf Goodman, and Neiman Marcus.

Cannon has styled fashion shows for Jason Wu and the Life Ball in Vienna, Austria, starring THE BLONDS, which is the largest AIDS benefit runway show in the world, that year hosted by President Bill Clinton and Eva Longoria. Other fashion shows include Snoopy in Fashion, Joanna Mastrioni to name a few. He has also styled shows for Safilo and their licensed brands, which include Gucci, Christian Dior, Emporio Armani, Ralph Lauren, Dior Homme, Max Mara, Marc Jacobs, Marc by Marc Jacobs, Stella McCartney, Banana Republic, Tommy Hilfiger.

Read Next