Olivier Bertrand – Cardboard Sculptures

Agnese La Spisa

From Web Designer to Wildlife Whisperer: The Cardboard Sculptures of Olivier Bertrand

If you had told Olivier Bertrand ten years ago that he’d become known as the guy who builds monumental animal sculptures out of cardboard, he would’ve probably laughed. Before this material took over his home (and his career), Bertrand was a web designer. It was a job he pursued after earning a Master’s in Economics. But deep down, the kid who spent childhood folding origami animals and sketching imaginary worlds never truly went away. It just took a long break. His journey began in the least glamorous way possible. A knee surgery, some free time, and a pile of cardboard boxes stared at him like, “Well? Do something.”

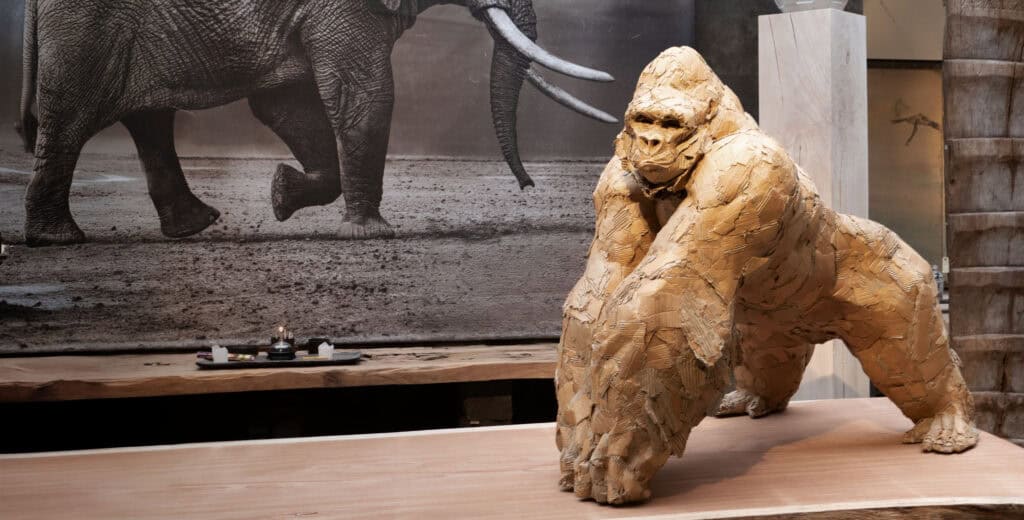

From there, something clicked. After two decades crafting virtual worlds, Olivier rediscovered the joy of making something you can actually touch. Cardboard, fragile, temporary, and unpredictable, became the perfect contrast to the powerful, often endangered animals he wanted to portray. What came next was wild. Animal sculptor Aurélien Raynaud saw the work and urged him to show it publicly. Months later, Olivier debuted at the Grand Palais during Art Capital 2019. There, his very gorilla won the Bronze Medal, a rare honor for a newcomer.

Today, Olivier’s work has been showcased in major venues. It is celebrated by peers and embraced by audiences who connect deeply with this strange but poetic tension. Strong animals made from the frailest material possible. It’s nature, vulnerability, and childhood imagination wrapped into one very unconventional medium.

Let’s step into his Olivier Bertrand’s world, one recycled sheet at a time.

Your journey brought you back to art after many years working as a web designer. What did it feel like to reconnect with your earliest creative impulses, and how did that rediscovery reshape your relationship to your own creativity?

Bertrand: After twenty years working in the world of virtual production as a web designer, returning to a tangible material felt incredibly liberating. It was almost a form of catharsis. I was suddenly creating something concrete, something physical. Something that truly existed in the world. It felt like going back to my roots, to what drove me as a child: creating with whatever I had on hand.

I had never sculpted before; I mostly drew. Moving into three-dimensional work expanded everything for me. Where my creativity had once been limited by my ability to create the illusion of volume on a flat surface, sculpture offered me an unexpected freedom. Everything became simpler, more intuitive. It was like rediscovering a language I had been speaking my entire life without realizing it.

Your sculptures transform a discarded everyday material into powerful, life-size animals. What first drew you to cardboard, and what happens emotionally for you in this act of elevating what is usually thrown away?

Bertrand: My connection to cardboard happened naturally. I was stuck at home after knee surgery, and the cardboard was simply there: accessible, familiar. It wasn’t a political gesture or a premeditated choice.

Since childhood, I had been building sets, robots, and spaceships out of whatever I could find: packaging, styrofoam… Working in volume has always been my most instinctive creative terrain.

It was only later, when this practice became my profession, that I realized the symbolic weight of the material. In a world where sustainability has become a crucial issue, transforming a disposable material into monumental sculptures carries a resonance of its own. It adds an unexpected, almost poetic dimension to my work.

You’ve spoken about the contrast between the strength of the animals you depict and the fragility of the cardboard itself. What conversations about nature, vulnerability, and extinction are you hoping your work inspires?

Bertrand: The fragility of cardboard brings something essential to my sculptures. Because it is perishable, it makes my subjects feel more alive; life being, by definition, fleeting. I try not to create “statues,” fixed and immutable, but rather living sculptures, pieces that seem to breathe.

I believe that, consciously or not, this speaks to people who connect with my work. Even though I often choose powerful animals as subjects, the nature of the material gives them a certain vulnerability. I want my subjects to be both beautiful and fragile, like all living things. I hope this tension (the strength of the subject and the fragility of the material) resonates with viewers. It evokes the condition of endangered species, but also our own delicate relationship with the natural world.

Olivier Bertrand sculptures involve precise architecture, interlocking armatures and integrated metal supports. How did your technical approach evolved?

Bertrand: With experience, I’ve learned to use as little internal armature as possible. I realized over time that a precise structure actually limits my freedom and intuition. It constrains me and forces me to follow a predefined plan. When you’re immersed in the creation of a piece, you always want to deviate from that plan. You want to change the angle of a limb, shift the pelvis, tilt the head differently. Today, whenever I can avoid using metal, I do. And when I must use it, I limit myself to a simple rod connected to the base, just enough to keep the sculpture balanced.

One of my earliest lessons came with my first gorilla: I couldn’t get it out of my living room to take it to the Grand Palais! I had to cut it apart and invent a system of interlocking pieces, almost like a Lego, straight back to childhood. Since then, this technique has allowed me to create monumental sculptures while still being able to transport them easily.

The moment Aurélien Raynaud encouraged you to show your work, and your award at Art Capital, marked a new chapter. How did those experiences influence your confidence and your vision for what your practice could become?

Bertrand: Recognition from one’s peers changes everything. When you’re starting out, you often feel illegitimate, as though you haven’t earned your place yet. Aurélien Raynaud’s words were pivotal. Without them, I might never have found the courage to fully embrace an artistic career or I would have done so much later. The Grand Palais was my first real encounter with the public, and the moment I discovered that what I created had the power to move people. It was a decisive turning point for me. I realized that what I was doing had meaning.

Until then, I created for my own pleasure. It was almost a selfish act. But facing the public, seeing their reactions and feeling their emotions, made something shift. My work resonated with them, and I understood that I had something to offer others.

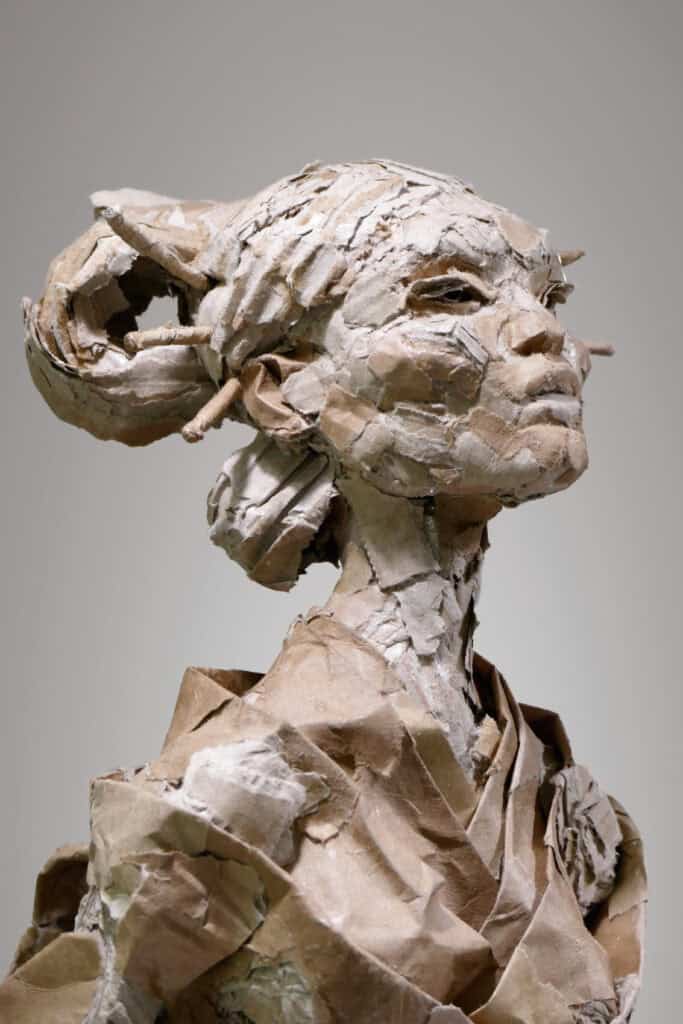

You also create human figures alongside the animal sculptures. What sparked this shift, and what new emotions or ideas are you Olivier Bertrand exploring, when the subject is the human body rather than the animal world?

Bertrand: I am a figurative artist, and my themes often come from my childhood: animals, mythology, Japanese warriors, everything connected to the living world. Over time, the human figure naturally found its place in my work. It allows me to explore fragility in a different way. A more intimate vulnerability, tied to identity, gesture, and emotion.

If animals allow me to speak about strength, disappearance, or nature, the human body introduces something more introspective, more narrative. It’s a natural extension of my universe, fully aligned with what I have always sought. To bring life to the humblest of materials while exploring the many forms of the living.

In the end, what makes Olivier Bertrand’s work so special isn’t just the cardboard, or the scale, or even the technique. It’s the feeling that he genuinely loves what he does. That childlike spark that survived adulthood, a career, and a detour through web design. His animals carry that energy with them.

Whatever creature he brings to life next, it’s clear Olivier is exactly where he’s meant to be. Surrounded by cardboard, following his instincts, and letting the wild world continue to unfold through his hands.

Share this post

Agnese La Spisa is an Italian creative based in Italy, specializing in publishing and fashion communication. At IRK Magazine, she brings together creativity, research, and design to shape stories with clarity and style. Curious and collaborative, she is driven by a passion for exploring culture, aesthetics, and the narratives that connect people, ideas, and disciplines.

Read Next