THE FIRST MOVEMENT, ERWIN OLAF

Thomas Werner

Drawn in by considered articulation and subjugated by beauty I am engulfed, or perhaps immobilized is a better word, by images that feel extraordinarily personal yet distant, untouchable. It is a visceral moment, much like being enveloped by a perfect rendition of Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, an experience that is both sensory and intellectual. It is with this in mind that I wait to talk with photographer Erwin Olaf, envisioning the same icy precision with a healthy dose of humanities shared melancholy that fills his images.

It is said that Olaf conceals the themes of his photographs, but he is telling his story, one that over the course of his career has also been our story. Not one of a sad or distant world, but one beginning with a young man filled with the aggressive exploration of youth, sexuality, and his place in the world followed by the evolution into manhood and the moment when mortality begins to confront us with the reality of our time frame and the early signs of physical limitations. Yet these are not solely the explorations of an individual, they are larger conversations of a society and culture. This is an elegant dialog filled with contemplative narratives where the audience can find meaning not only in beauty, but in the cracks that run through the characters and emotion filled spaces.

Erwin entered photography as journalism student. More of a street photographer than a photojournalist as he was covering the anti-nuclear and gay rights demonstrations of the 1980s. When asked why he chose this course of study Olaf elaborates, “I was 18, 19 years old ready to discover the world.” He goes on, “From the first second holding the camera and developing the film, doing the printing; this whole process felt far more natural to me than endlessly writing and rewriting…Working with a camera gives the possibility to get in touch with the world without being part of the world, because you can hide a little bit. Especially in the beginning with journalistic photography, but later in studio I had the possibility as well, because you get to create your own world, the deepest of your own world without being part of it because other people are acting your story.”

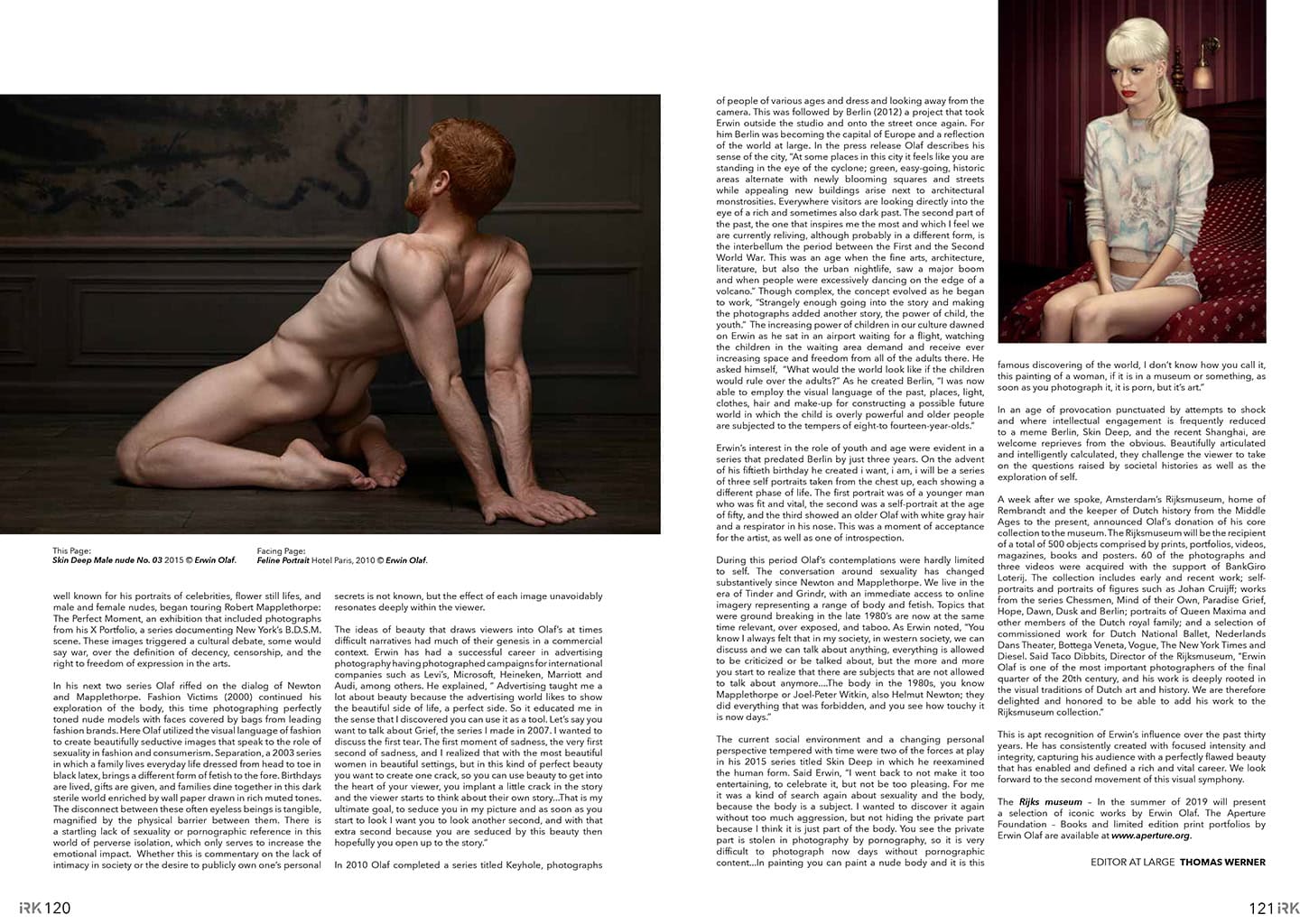

The move from photojournalism to photographic artist working in constructed narrative allowed a distance that provided the ability to “walk around an image” asking what might be done better technically or conceptually. This objective yet personal attention to detail can be seen throughout his career, evident in his first step onto the art world’s international stage when he was awarded first prize in the 1988 Young European Photographer Competition for his series Chessmen. These photographs were seeped in the influence of Joel-Peter Witkin, one of a handful of photographic artists from the period who were ground breaking in their engagement with the human form and photography’s role in challenging social boundaries. This early work by Olaf involved the study of the body, skin, nudity, sexuality, and it’s place in society, a subject that he has touched on throughout his career. During this period his exploration of the human form was more aggressive as it was representative of a young man asserting himself in the world visually and personally. “I was already part of the community, I came out of the closet and nobody said “Oh that’s wrong”, but sexuality was a kind of demon, you are looking for what you can deal with in sexuality”. During the 1980’s and early 1990’s a number of photographers were taking on the public emergence of diverse sexual social mores. Helmut Newton was continuing his exploration of sexuality, facade, fetish, voyeurism, and the erotic, while Witkin was creating macabre constructions with models of the most extraordinarily diverse body types. In 1989 Robert Mapplethorpe, already well known for his portraits of celebrities, flower still lifes, and male and female nudes, began touring Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment, an exhibition that included photographs from his X Portfolio, a series documenting New York’s B.D.S.M. scene. These images triggered a cultural debate, some would say war, over the definition of decency, censorship, and the right to freedom of expression in the arts.

In his next two series Olaf riffed on the dialog of Newton and Mapplethorpe. Fashion Victims (2000) continued his exploration of the body, this time photographing perfectly toned nude models with faces covered by bags from leading fashion brands. Here Olaf utilized the visual language of fashion to create beautifully seductive images that speak to the role of sexuality in fashion and consumerism. Separation, a 2003 series in which a family lives everyday life dressed from head to toe in black latex, brings a different form of fetish to the fore. Birthdays are lived, gifts are given, and families dine together in this dark sterile world enriched by wall paper drawn in rich muted tones. The disconnect between these often eyeless beings is tangible, magnified by the physical barrier between them. There is a startling lack of sexuality or pornographic reference in this world of perverse isolation, which only serves to increase the emotional impact. Whether this is commentary on the lack of intimacy in society or the desire to publicly own one’s personal secrets is not known, but the effect of each image unavoidably resonates deeply within the viewer.

The ideas of beauty that draws viewers into Olaf’s at times difficult narratives had much of their genesis in a commercial context. Erwin has had a successful career in advertising photography having photographed campaigns for international companies such as Levi’s, Microsoft, Heineken, Marriott and Audi, among others. He explained, “ Advertising taught me a lot about beauty because the advertising world likes to show the beautiful side of life, a perfect side. So it educated me in the sense that I discovered you can use it as a tool. Let’s say you want to talk about Grief, the series I made in 2007. I wanted to discuss the first tear. The first moment of sadness, the very first second of sadness, and I realized that with the most beautiful women in beautiful settings, but in this kind of perfect beauty you want to create one crack, so you can use beauty to get into the heart of your viewer, you implant a little crack in the story and the viewer starts to think about their own story…That is my ultimate goal, to seduce you in my picture and as soon as you start to look I want you to look another second, and with that extra second because you are seduced by this beauty then hopefully you open up to the story.”

In 2010 Olaf completed a series titled Keyhole, photographs of people of various ages and dress and looking away from the camera. This was followed by Berlin (2012) a project that took Erwin outside the studio and onto the street once again. For him Berlin was becoming the capital of Europe and a reflection of the world at large. In the press release Olaf describes his sense of the city, “At some places in this city, it feels like you are standing in the eye of the cyclone; green, easy-going, historic areas alternate with newly blooming squares and streets while appealing new buildings arise next to architectural monstrosities. Everywhere visitors are looking directly into the eye of a rich and sometimes also dark past. The second part of the past, the one that inspires me the most and which I feel we are currently reliving, although probably in a different form, is the interbellum the period between the First and the Second World War. This was an age when the fine arts, architecture, literature, but also the urban nightlife, saw a major boom and when people were excessively dancing on the edge of a volcano.” Though complex, the concept evolved as he began to work, “Strangely enough going into the story and making the photographs added another story, the power of child, the youth.” The increasing power of children in our culture dawned on Erwin as he sat in an airport waiting for a flight, watching the children in the waiting area demand and receive ever increasing space and freedom from all of the adults there. He asked himself, “What would the world look like if the children would rule over the adults?” As he created Berlin, “I was now able to employ the visual language of the past, places, light, clothes, hair and make-up for constructing a possible future world in which the child is overly powerful and older people are subjected to the tempers of eight-to fourteen-year-olds.”

Erwin’s interest in the role of youth and age were evident in a series that predated Berlin by just three years. On the advent of his fiftieth birthday he created i want, i am, i will be a series of three self portraits taken from the chest up, each showing a different phase of life. The first portrait was of a younger man who was fit and vital, the second was a self-portrait at the age of fifty, and the third showed an older Olaf with white gray hair and a respirator in his nose. This was a moment of acceptance for the artist, as well as one of introspection.

During this period Olaf’s contemplations were hardly limited to self. The conversation around sexuality has changed substantively since Newton and Mapplethorpe. We live in the era of Tinder and Grindr, with an immediate access to online imagery representing a range of body and fetish. Topics that were ground breaking in the late 1980’s are now at the same time relevant, over exposed, and taboo. As Erwin noted, “You know I always felt that in my society, in western society, we can discuss and we can talk about anything, everything is allowed to be criticized or be talked about, but the more and more you start to realize that there are subjects that are not allowed to talk about anymore….The body in the 1980s, you know Mapplethorpe or Joel-Peter Witkin, also Helmut Newton; they did everything that was forbidden, and you see how touchy it is now days.”

The current social environment and a changing personal perspective tempered with time were two of the forces at play in his 2015 series titled Skin Deep in which he reexamined the human form. Said Erwin, “I went back to not make it too entertaining, to celebrate it, but not be too pleasing. For me it was a kind of search again about sexuality and the body, because the body is a subject. I wanted to discover it again without too much aggression, but not hiding the private part because I think it is just part of the body. You see the private part is stolen in photography by pornography, so it is very difficult to photograph now days without pornographic content…In painting you can paint a nude body and it is this famous discovering of the world, I don’t know how you call it, this painting of a woman, if it is in a museum or something, as soon as you photograph it, it is porn, but its art.”

In an age of provocation punctuated by attempts to shock and where intellectual engagement is frequently reduced to a meme Berlin, Skin Deep, and the recent Shanghai, are welcome reprieves from the obvious. Beautifully articulated and intelligently calculated, they challenge the viewer to take on the questions raised by societal histories as well as the exploration of self.

A week after we spoke, Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, home of Rembrandt and the keeper of Dutch history from the Middle Ages to the present, announced Olaf’s donation of his core collection to the museum. The Rijksmuseum will be the recipient of a total of 500 objects comprised by prints, portfolios, videos, magazines, books and posters. 60 of the photographs and three videos were acquired with the support of BankGiro Loterij. The collection includes early and recent work; self-portraits and portraits of figures such as Johan Cruijff; works from the series Chessmen, Mind of their Own, Paradise Grief, Hope, Dawn, Dusk and Berlin; portraits of Queen Maxima and other members of the Dutch royal family; and a selection of commissioned work for Dutch National Ballet, Nederlands Dans Theater, Bottega Veneta, Vogue, The New York Times and Diesel. Said Taco Dibbits, Director of the Rijksmuseum, “Erwin Olaf is one of the most important photographers of the final quarter of the 20th century, and his work is deeply rooted in the visual traditions of Dutch art and history. We are therefore delighted and honored to be able to add his work to the Rijksmuseum collection.”

This is apt recognition of Erwin’s influence over the past thirty years. He has consistently created with focused intensity and integrity, capturing his audience with a perfectly flawed beauty that has enabled and defined a rich and vital career. We look forward to the second movement of this visual symphony.

The Rijksmuseum – In the summer of 2019 the museum will present a selection of iconic works by Erwin Olaf

The Aperture Foundation – Books and limited edition print portfolios by Erwin Olaf are available at www.aperture.org

The First Movement, by Thomas Werner @Thomaswernerprojects

Purchase a PDF of the entire Masters issue at: https://www.irkmagazine.com/shop

Share this post

Thomas is the author of the books The Business of Fine Art Photography, Routledge, New York, and The Fashion Image for Bloomsbury Publishing, London, with an upcoming book co-authored with Microsoft BING and AI team leader Derrick Connell due out in early 2026. He is also an Editor at Large for IRKmagazine, Board Member for the Santa Fe Council CENTER for Photographic Art, and past Photography Program Director at Parsons School of Design in New York. He is the former owner of Thomas Werner Gallery in Manhattan’s Chelsea Art District, and a former National Board member and New York Chapter President for the American Society of Media Photographers. As well as a former Advisory Board Member for Ithaca College’s Executive Education Program, contributor to Adobe’s Lightroom Academy, and a photography consultant for COACH, among others.

Werner led a team developing a media and literacy website for the United Nations Alliance of Civilizations/UNESCO and was a recurring instructor for the United Nations Education First Summer School. From 2005 – 2019 he worked with the United States Department of State on cultural projects in Russia partnering with 32 cultural, educational, and governmental organizations to develop projects in 29 cities. As an exhibiting artist Thomas was represented by galleries in New York and Los Angeles, and his work reviewed in The New Yorker Magazine.

Currently a creative consultant, Thomas works one on one with students, creatives, businesses, cultural institutions, and not for profits, helping them with career development, team management, innovation, education, professional practices, and the development of effective communication across multiple media platforms.

For fourteen years his research was Russia centric spending an average of 30 days a year in the country. The focus was the introduction of contemporary education methodologies, and the development of creative cultures within the country. Russian partners have included; The State Hermitage Museum, the National Center of Contemporary Art, Perm Regional Government, The Moscow Biennale for Young Art, National Centre of Photography for the Russian Federation, The Central State Archive of Film, Photographic and Phonographic Documents, The Moscow Biennale, The Pro Arte Foundation, and others. He has curated exhibitions in the United States and abroad, including seven co-curated exhibitions at the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia. His private collection of Russian photographs and artifacts have been exhibited internationally.

Thomaswernerprojects.com @Thomaswernerprojects IG

Read Next